Home » Posts tagged 'prisoners' (Page 2)

Tag Archives: prisoners

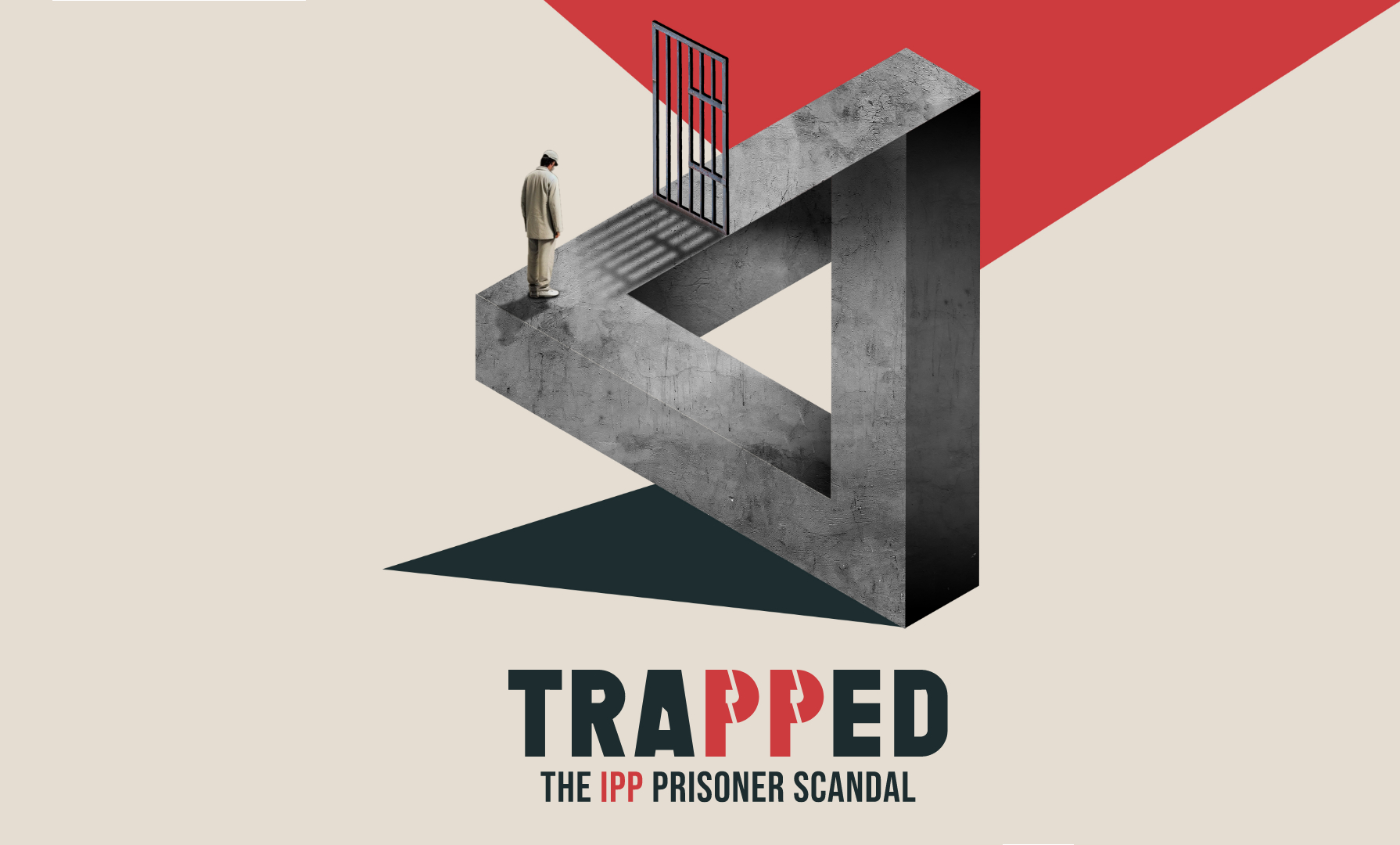

Let’s end this injustice now, TOGETHER: IPP Scandal

The momentum is building, and more of society are becoming aware of the IPP Scandal, where prisoners can be languishing in prison with no end date to their sentence. Over 80 with an IPP sentence have taken their own life, their hope deferred time and time again. This sentence was abolished in 2012, but not retrospectively. Stories of those caught up in this tragedy in our justice system can be heard in a series of podcasts, by the Zinc Media Group. Click HERE for the link.

Sir Bob Neil MP has tabled an amendment to the Victims and Prisoners Bill to implement the recommendation of the Justice Select Committee to re-sentence all IPPs. In order for this to happen we need this amendment supported by the majority of MPs from all parties.

This is where we all can assist.

Firstly: click HERE to watch a film By Peter Stefanovic highlighting the injustice for those serving an IPP sentence. It has now been viewed over 2.5M times.

Secondly: repost this video and tag your MP. If you are not sure the name of your MP, click HERE to find out .

Thirdly: write to your MP. Below is a template produced by UNGRIPP, that can be used to encourage your MP to vote to accept the important amendment for re-sentencing.

Click HERE for the link and explanation of how to prepare and send, or copy and paste the sample letter below. Of course, if you do not have access to a printer or simply prefer to hand write letters, then feel free to use part of this sample letter. MPs pay particular attention to hand written letters.

{YOUR FULL NAME}

{YOUR FULL ADDRESS}

{YOUR POSTCODE}

{EMAIL ADDRESS}

{DATE}

Dear {MP NAME},

My name is {YOUR NAME} and I am a constituent of {YOUR CONSTITUENCY/AREA WHERE YOU LIVE}. I am writing to you because I would like to see changes made to the Indeterminate Sentence for Public Protection (known as the IPP sentence); a type of indefinite sentence given to 8,711 people between 2005 and 2013 for a wide range of major and minor crimes, and abolished by the Government in 2012. I have enclosed further information about the sentence, in case you are not already aware of it.

I would like you to take forward my concerns, set out below, by backing Amendment NC1 to the Victims and Prisoners Bill, proposed by Sir Bob Neill, Chair of the Justice Select Committee. The amendment, entitled ‘Resentencing those serving a sentence of Imprisonment for Public Protection’ would make provision a resentencing exercise carefully planned by an expert group. You can view the full amendment here: https://bills.parliament.uk/bills/3443/stages/17863/amendments/10008642

In August 2023, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture stated the Government should urgently review IPP. They expressed ‘serious alarm’ about the suicides of people serving an IPP sentence (a concern recently echoed by the Prison & Probation Ombudsman), and stated that the sentence ‘violates basic principles of fair justice and the rule of law.’

As a member of the public, I am concerned that thousands of people are still serving an abolished sentence condemned by an international human rights body on torture. I do not think such a sentence has any place in our justice system. As you may already be aware, the IPP sentence was abolished because it was agreed to be unjust and ineffective. Thousands of people were given a life sentence for crimes that would never attract a life sentence today. The sentence was based on the premise that we can accurately predict a person’s risk of committing future crime; something that is complex, difficult, and flawed. It is a stain on the reputation of our justice system that thousands of people are still subject to an abolished sentence, and have served years longer than the time it was agreed they deserved as punishment. It is also reprehensible that their families and children continue to suffer the consequences. {IF YOU WANT TO, ADD YOUR EXTRA THOUGHTS ON THE SENTENCE HERE, AND EDIT THE ABOVE TO REFLECT YOUR VIEWS}

In 2022, the Justice Select Committee published a report on their inquiry into the IPP sentence. The report gives a damning indictment of a regime of indefinite detention that has caused widely documented harm, and departed from public notions of justice, fairness and proportionality.

The Committee concluded that even though there are ways to improve how the IPP sentence works, there is no way to truly fix it, and it is “irredeemably flawed”. Their main recommendation is a resentencing exercise. That means that everybody serving IPP would be individually resentenced by a judge, to a sentence available under current sentencing law, following the principle of balancing public protection with justice, judicial independence, and the appointment of an independent panel to implement the exercise.

I would be grateful if you would speak to the Secretary of State for Justice, Alex Chalk and request that he consider the proposed amendment, as well as advocating for it yourself. Shadow Justice Minister Ellie Reeves signalled in a Westminster Hall debate on 27th April 2023 that Labour will work constructively with the Conservatives in a cross-party effort on this issue.

The upcoming proposed amendment to the Victims and Prisoners Bill is a window of opportunity to rectify the wrongs to a sentence that has been condemned by the European Court of Human Rights, the Prison Reform Trust, the Howard League, Liberty, Amnesty International, the former Home Secretary who introduced the sentence (Lord Blunkett), and the former Lord Chief Justice Lord Brown who has called it “the greatest single stain on our justice system”. Your help on this matter is crucial.

If you are unable to address this personally, I would like to request that you escalate my letter to the relevant Minister or department. Please do keep me informed of any progress made. I look forward to hearing from you.

Yours faithfully,

{YOUR NAME}

Finally: remember to show your support on social media for those campaigning hard for the vital change in re-sentencing all those trapped within the IPP sentence.

Thank you

TOGETHER we can end this injustice.

The watering down of prison scrutiny bodies

I want to concentrate on two scrutiny bodies: His Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons (HMIP) and the Independent Monitoring Boards (IMB).

It appears that both have changed their remit to compensate for the ineffectiveness of their scrutiny. Are they trying to improve something, or are they trying to hide something?

Does the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) want these bodies to obfuscate the facts of the state of prisons? The dilution of scrutiny results in degradation of conditions for your loved ones in prison, staff and inmates alike, both in the same boat.

His Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons (HMIP)

Website https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons/

HMIP inspections have routinely issued recommendations to prisons where failure in certain areas needed to be addressed and in cases where it is possible for issues to be rectified or improved. Applying the healthy prison test, prisons are rated on the outcomes for the four categories below:

- Safety

- Care

- Purposeful activity

- Resettlement

Since 2017, if the state of a prison is of particular concern an Urgent Notification (UN) has been issued. This gives the Secretary of State 28 calendar days to publicly respond to the Urgent Notification and to the concerns raised in it. There have been twelve Urgent Notifications issued so far, and the details from the latest urgent notification for HMYOI Cookham Wood, for example, is uncomfortable reading:

“Complete breakdown of behaviour management”

“Solitary confinement of children had become normalised”

“The leadership team lacked cohesion and had failed to drive up standards”

“Evidence of the acceptance of low standards was widespread”

“Education, skills and work provision had declined and was inadequate in all areas”

“450 staff were currently employed at Cookham Wood. The fact that such rich resources were delivering this unacceptable service for 77 children indicated that much of it was currently wasted, underused or in need of reorganisation to improve outcomes at the site.”

Source: https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2023/04/HMYOI-Cookham-Wood-Urgent-Notification-1.pdf

However, the Inspectorate now have a new system where recommendations have been replaced by 15 key concerns, of these 15, there will be a maximum of 6 priorities. On their website it states:

“We are advised that “change aims to encourage leaders to act on inspection reports in a way which generates real improvements in outcomes for those detained…”

Source: https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons/about-our-inspections/reporting-inspection-findings/

One of my concerns is whether this change will act as a pretext to unresolved issues being formally swept under the carpet. A further concern is what was seen as a problem previously will now be accepted as the norm. As a consequence how will the public be able to get a true and full picture of the state of the prisons?

Will there be a reduction in Urgent Notifications?

I think not.

Or will the issuing of urgent notifications be the only way to get the Secretary of State for Justice to listen and act? In my view, issues that would previously have been flagged up during an inspection are more likely to disappear into the abyss along with all past recommendations which have been left and ignored.

Could it be said that this change of reporting is a watering down of inspection scrutiny that you expect of the Inspectorate?

Before you answer that, let’s look at the IMB.

Independent Monitoring Board (IMB)

Website: https://imb.org.uk/

Until very recently, the Independent Monitoring Board (IMB) website stated that for members: “Their role is to monitor the day-to-day life in their local prison or removal centre and ensure that proper standards of care and decency are maintained.”

But looking at the IMB website today I have noticed that they have changed their role. Instead, it now states that members: “They report on whether the individuals held there are being treated fairly and humanely and whether prisoners are being given the support they need to turn their lives around.”

Contrast that with what the Government website http://www.gov.uk displays, where you will find two more alternatives to what the IMB do:

- 1st. “Independent Monitoring Boards (IMBs) monitor the treatment received by those detained in custody to confirm it is fair, just and humane, by observing the compliance with relevant rules and standards of decency.”

Source: https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/independent-monitoring-boards-of-prisons-immigration-removal-centres-and-short-term-holding-rooms

The first is a large remit for volunteers as there are rather a lot of rules to be aware of. I’m sure the IMB training is unable to cover them all, so how can members be required to know if the prison is compliant or not.

- 2nd. “Independent Monitoring Boards check the day-to-day standards of prisons – each prison has one associated with it. You don’t need specific qualifications and you get trained.”

Source: https://www.gov.uk/volunteer-to-check-standards-in-prison

This checking comes across as a mere tick box exercise, which it certainly should not be. Again, I question whether IMB members training is sufficient. What they say and what actually happens is another example of the absence of ‘joined-up’ government.

In point of fact, the IMB has never been able to ensure anything; if it had then they have completely failed in their remit, as evidenced by the decline in the state of prisons in England and Wales. Clarifying their role is an important change, and one I have been calling out the IMB on for years.

Could it be said that this change of wording is a watering down of monitoring scrutiny you can expect of IMB members?

To help you answer that, you may also need to consider the following:

Although the IMB has become a little more visible, I still have to question their sincerity whether they are the eyes and ears in the prisons of society, of the Justice Secretary, or of anyone else?

The new strapline adopted by IMB says: “Our eyes on the inside, a voice on the outside.” Admirable ambition, and yet compare that with the lived reality, for example, of my being the eyes on the inside and a voice on the outside, which was exactly the reason why, in 2016, I was targeted in a revolt by the IMB I chaired, suspended by the then Prisons Minister Andrew Selous MP. For being the eyes on the inside and a voice on the outside I was subjected to two investigations by Ministry of Justice civil servants (at the taxpayer’s expense), called to a disciplinary hearing at MoJ headquarters 102 Petty France, then dismissed and banned from the IMB for five years from January 2017 by the then Prisons Minister, Sam Gyimah MP.

If the prisons inspectorate have one sure-fire way of attracting the attention of the Secretary of State for Justice in the form of an Urgent Notification, then why doesn’t the IMB have one too? Surely the IMB ought to be more aware of issues whilst monitoring as they are present each month, and in some cases each week, in prisons. Their board members work on a rota basis. Or should at least.

And then of course there is still the persistent conundrum that these two scrutiny bodies are operationally and functionally dependent on – not independent of – the Ministry of Justice, which makes me question how they comply with this country’s obligation to United Nations, to the UK National Preventative Mechanism (NPM) and Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and other Cruel Inhuman of Degrading Treatment or Punishment (OPCAT), which require members to be operationally and functionally independent.

In 2020, I wrote: “When you look long enough at failure rate of recommendations, you realise that the consequences of inaction have been dire. And will continue to worsen whilst we have nothing more compelling at our disposal than writing recommendations or making recommendations.”

and: “Recommendations have their place but there needs to be something else, something with teeth, something with gravitas way beyond a mere recommendation.”

As a prisons commentator I will watch and wait to see if the apparent watering down of both of these organisations will have a positive or detrimental effect on those who work in our prison environments and on those who are incarcerated by the prison system.

As Elisabeth Davies, the new National Chair of the Independent Monitoring Boards, takes up her role from 1st July 2023 for an initial term of three years, I hope that the IMB will find ways to no longer be described as “the old folk that are part of the MoJ” and stand up to fulfil the claim made in their new strapline: “Our eyes on the inside, a voice on the outside”.

And drop the misleading title “Independent.”

~

Photo: Pexels / Jill Burrow. Creative Commons

~

Penitence versus Redemption in the Criminal Justice System: Unedited

I once entered a cell of a high-profile prisoner; his crime had been blazoned on every national newspaper and was serving the last few months of his sentence as an education orderly. He sat on his raised bed, his legs dangling over the menial storage where he had meticulously and precisely arranged his pairs of trainers and invited me to sit on the only chair in the cell. During our 20-minute conversation, he was pensive and reflective, looking down all the while, except for when he raised his head, adjusted his glasses, then looked me straight in the eye.

“Don’t count the days, but make every day count,” he said, his voice monotone and hushed. Yet behind him, I noticed a calendar marked with neatly drawn crosses. He was clearly counting down his days, paying his penitence until his eventual release from prison.

As an independent criminologist, I have met many who feel a deep-seated obligation to “pay back” continuously in some way to society or a higher power. Those who are caught and convicted for committing a crime experience punishment in some form or other, but when should that punishment end? Is it once a sentence has been served or longer?

Over the last 12 years, I have visited every category of prison in England and Wales and monitored a Category D prison for four years. In all that time, I have encountered hundreds of inmates, many struggling with the punishment, not only that of the sentence given by the courts, but the continual punishment they experience as they serve it, as well as after release and beyond.

The Ministry of Justice proudly states on their website that their responsibility is to ensure that sentences are served, and offenders are encouraged to turn their lives around and become law-abiding citizens. Apparently, the Ministry has a vision of delivering a world-class justice system that works for everyone in society, and one of four of their strategic priorities is having a prison and probation service that reforms offenders.

But I am not at all convinced by this hyperbole. In my opinion, we must stop the madness of believing that we can change people and their behaviour by banging them up in warehouse conditions with little to do, not enough to eat, and sanitation from a previous century.

Penitence

If true reform is supposed to be achieved through time served, then a former inmate emerging from prison with a clean slate would be ready to contribute fully to society. Yet beyond prison gates people who have served their time all too often live under a cloud of penitence, suppressing a sense of guilt for their deeds.

Many of the formerly incarcerated insist on a daily act of penitence, a good deed, even raising money for a worthy cause. For onlookers, such acts carry an air of respectability, but it is important to understand what is really happening on the inside because some of those who engage in them do so as a form of self-punishment. The punishing of self both physically and mentally.

They sense they must compensate.

Their account never fully paid.

Lifelong indebtedness.

And of course there are those who appear to genuflect to the Ministry of Justice and the Criminal Justice System; a sign of respect or an act of worship to those always in a superior position.

On the balance of probabilities, it is more likely than not that some penal reform organisations and some individuals with lived experience approach the Ministry of Justice with such reverence showing their cursory act of respect.

The same act of penitence or faux reverence ingrained into them whilst they served their custodial sentence.

For others penitence is an act devoid of meaning or performed without knowledge.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the definition of penitence is “the action of feeling or showing sorrow and regret for having done wrong, repentance, a public display of penitence.” In addition to the formal punishment they endure, many prisoners engage in penitence both physically and mentally during and after serving their time, which keeps them from moving forward with their lives and is damaging to their sanity.

According to a 2021 report by the Centre for Mental Health, (page 24) “former prisoners…had significantly greater current mental health problems across the full spectrum of mental health diagnosis than the general public, alongside greater suicide risk, typically multiple mental health problems including dual diagnosis, and also lower verbal IQ…and greater current social problems.”

In my work, I have found that some people who have broken the law want others to know that they are sorry, whilst at the same time feel the pressure to prove this to themselves. In such cases, their penitence becomes a public display for families, caseworkers, and those in authority.

Witnesses to this display of penitence often think these people are a good example of someone who has turned their life around, but often, these former prisoners find themselves stuck in the act of penitence. Rather than turning their lives around, they are trapped forever in their guilt. In these cases, the act of atoning becomes all-consuming, an insatiable appetite to heed the voices in their soul that tell them, “you must do more and more, it’s not enough, I’m hungry.”

Redemption

When I speak to those who are serving a whole-life tariff, I know that their debt to society can never be repaid: they are resigned to a lifelong burden of irredeemable indebtedness. But many of those who are released from prison remain incarcerated by their own guilt, feeling as if they must hide any hint of happiness they may find in life after prison so as not to be judged.

For example, in 2019, I interviewed Erwin James, author, Guardian columnist and convicted murderer, who had just come out with his third book, Redeemable: a Memoir of Darkness and Hope. When I asked him, “What makes you happy?” he replied: “In the public, if I am laughing, I feel awful because there are people grieving because of me. Even in jail, I was scared to laugh sometimes because it looked like I didn’t care about anything.”

Just like I saw with the prisoner sat on his bed, I have witnessed a cloud hanging over many, especially when redemption, or the act of repaying the value of something lost, relates to acceptance and society’s opinion of you.

There are of course prisoners who have the intellectual capacity to learn from their mistakes, have the emotional capacity to adapt to their situations and – not forgetting – the spiritual capacity, a dimension that can lead to a voyage of self-discovery. But by no means all.

Unfortunately, in the UK, paying back to society can either be the light at the end of the tunnel, or a tunnel with no light.

I believe we live in a punitive society in which the continual punishment of those who have offended is tacitly endorsed. In so doing, society inadvertently encourages the penitentiaries of this world to hold offenders in an ever-tightening grip.

Even a sentence served in the community—a sentencing option all too often shunned by magistrates—can carry an arduous stigma. In a public show of humiliation, the words “Community Payback” are garishly emblasoned on the offenders’ brightly-coloured outerwear, announcing their status as a wrongdoer to all who see them. Basically, this is society’s way of saying, “we want you to be sorry, we want you to show you are sorry and we will not let you forget it.”

Statements such as “the loss of liberty is the punishment” become fictitious, enabling punishment in its various form to continue throughout the sentence served and even after release.

Let us no longer have this traditional stance, rather should we try to embolden others to move on from their actions?

And can groundless nimbyism be finally assigned to history?

I am mindful that pain and grief still abounds, that some crimes will not be erased from our minds, and that crimes will stubbornly continue. But surely, the answer cannot be to condemn those who have done wrong to a lifetime without forgiveness.

To move forward as a society, we need to discourage the continual need to offer an apology, and instead accept when former prisoners have paid their dues and served their sentences. Only then will we move from a vicious cycle of unending penitence to a world in which reform and redemption is truly possible.

~

An edited version of this article was first published on 28 February 2022 by New Thinking.

~

IMB Soap Opera

Is the IMB like liquid soap?

Not the wonderful clear stuff which has a beautiful fragrance and an antibacterial effect on everything it touches.

No, not that.

More like that gawd awful stuff you find in greasy dispensers at motorway service station toilets, where hygiene means tick boxing inspection sheets on the back of the door. Its colour an insipid artificial pink like slime from old boiled sweets left too long in the sun, and its smell nauseous like cat sick.

But it is its opacity that irks me.

Designed to deliberately obfuscate, smother and shroud all that has any proximity to it, you never truly know whether it has any cleansing properties at all.

I neither like nor trust opaque liquid soap.

I happily tolerate the clear stuff, so long as it really is clear and totally free of nasty microbeads, creaming additives and fake foam.

It would have been far better for the IMB if it had been a bar of soap. At least you know where you are with a bar of soap. Visible, tangible, relatable, practical, and likeable. A bar of soap has these and many other qualities about it which reassures me of its fitness for purpose.

From the moment it is unwrapped and placed at the side of the sink, its very presence reassures you. Sitting there unblemished and ready to serve, a fresh bar of soap exudes a sense of personalised attentiveness and an unwillingness to be corrupted by falling into the wrong person’s hands.

I don’t think it is too much to ask that a bar of soap is fresh and that I am the first person to use it. There are some things that are unacceptable to pass around.

Even if we were to believe all they tell us then, at best, IMB would resemble a remnant of used soap, cracked and old. Once so full of purpose, now degraded in the hands of multiple ministers and permanent secretaries. Put on the side, its usefulness expended but its stubborn existence more a token gesture of monitoring rather than an effective part of the hygiene of the justice system.

It is an exhausted specimen of uselessness despite what its National Chair, Secretariat, Management Board would have you believe. They justify their own sense of importance with the sort of job roles that place them on a pedestal. But in reality it all just smacks of self aggrandizement; as they say in Texas – “Big hat, no cattle.”

Where once I bought into this whole parade, now I see it for the parody that it is. Where once I was pleased to serve, now I call out the servitude that the system enforces on those who work within it.

Where once I would write the annual reports, now I challenge the pointlessness of recording observations and making recommendations, an utterly futile exercise because there was never any intention by the Ministry of Justice to do anything about them.

A fresh bar of soap has an impressive versatility about it. It can give you clean hands, yes, but it can go a lot further than that. It can be carved, shaped and fashioned into an object of extraordinary beauty.

Some people serving their time in prison surprise me when they produce such intricate objects crafted from something as humble as a fresh bar of soap; an allegory of their own lives, in some cases I have known. Arguably a work of art to be admired and cherished.

Whereas an old, cracked bar of soap has no such versatility or value, and does not merit being kept.

If you can’t wash your hands with it, you should wash your hands of it.

In its present form, the IMB needs to be replaced.

~

A conversation with: Lady Val Corbett, passionate about prison reform, empowerment of women and kindness in business

Lady Val Corbett, a feisty woman, with determination to rival most, striking red hair and a penchant for wearing bright scarves, is one way of introducing my latest “A conversation with…” Having known Lady Val for 6 years, I have found her to be compassionate, hilarious, focused and above all, a friend.

Her career in journalism started in Cape Town but with moving to the UK it was impossible to continue without being a member of the National Union of Journalists. Eventually she worked for the Sunday Express as a weekend reporter; a Features Editor of a noteworthy Furnishing Magazine; Editor of a magazine Woman’s Chronicle for the Spar customers and grocers which then led to becoming the consumer columnist on The Sun. With the birth of her daughter, Polly, she invented herself several times!

“I wrote a column for Cosmopolitan and for national papers and magazines plus scriptwriter for BBC TV then became one of the founder directors of an independent TV production company which sold programmes for major broadcasters – highlight was a six-part BBC1 series called Living with the Enemy on teenagers as I was struggling with mine at the time. I was a volunteer at the Hoxton Apprentice, a training restaurant for long term unemployed and saw how people could change direction. After that I co-wrote six novels with two friends and in between was an MP’s wife and later the PA for Lord Corbett of Castle Vale, when I regularly gave notice or got fired.”

That’s quite a résumé.

Val had a chance encounter on her first day as a features writer, which led to 42 years of happy marriage.

“On my first day I was having second thoughts about a new dress I had bought. Going to the canteen for lunch I paused at the door and asked my colleague: “Does this dress make me look dumpy?” To which an amused male voice said: “Yes it does.” I looked up – my 5ft 2” to his 6ft 3” – and thought he was the rudest man I’d ever met. He called me Dumpy for ages.”

Her husband, Lord Corbett of Castle Vale, sadly died on 19th February 2012.

Did you personally have an interest in politics?

Not for party politics. I knew apartheid was wrong, unfair, and cruel. My first time voting as a British citizen was in Fulham when I put my cross next to Major Wilmot-Seale whom I believed was the Liberal candidate (party allegiances were not then on ballot papers). He was the National Front candidate and garnered 45 votes of which mine was one. Robin never let me forget this. Over the years he became my political mentor because he thought going into politics was because you wanted to change the world. And goodness how he tried!

When Robin decided a cause was just, he was not swayed from the path, do you feel you have taken on that mantle?

I could have chosen from several of his crusades – his Private Members Bill which became law, granting lifetime anonymity for rape victims in courts and media was one but he was also active in prison reform during his 34-year parliamentary career. Chairing the All-Party Penal Affairs Group for 10 years until his death made him realist how much there was to do in the criminal justice system.

He used to say: “Prison isn’t full of bad people; it’s full of people who’ve done bad things and most need a chance to change direction.”

Was it a mantle you were willing to take on?

Yes, when I heard a man say on TV “All men die but some men live on.” I wanted Robin’s legacy in prison reform to live on. Though a novice in prison reform I immersed myself in prison reform in 2013 and though I am still learning now feel I am no longer a novice.

What makes you laugh?

I laugh a lot particularly at short jokes and always tell one or two at my professional women’s network events.

What makes you cry?

Anything concerning cruelty to children.

Since 2016, I have been part of Lady Val’s Professional Women’s Network consisting of female entrepreneurs, senior women in business, the arts, government, investment, HR, and many more diverse professions.

It’s a forum for women in business looking to further their careers by focusing on leadership skills, self-confidence, and other key areas of personal development. Meeting five times per year for lunch, each event starts with an icebreaker “How can I help you and how can you help me”, a simple formula which encourages meaningful connections. This is followed by an inspirational speaker, a leader in their field sharing business knowledge and expertise.

The professional networking lunches are all about business and not entertainment, how do you reflect that in your choice of speakers?

I choose keynote speakers with care. Most speakers have been leaders in their field of business: marketing, fin tech, green economy, Lloyds of London, Abbey Road Studios etc. We had Michael Palin and Jon Snow, both prison reform campaigners, also Prue Leith and Jeffrey Archer. They attracted large audiences, but the Network is a business one, not an entertainment one… So, we are going back to basics, with speakers appealing to businesswomen. I’m happy that through the contacts not only have networkers gained business contacts but also friends.

We are all in this together and if women don’t help each other, who will?

What in your opinion are some of the barriers for women to advance in their professional lives?

The main barrier is a lack of confidence. The glass ceiling is there to be smashed but few women want to. This is changing though not fast enough for me! I count myself not as a feminist but as an equalist and am proud that the wearethecity.com network voted me one of their 50 Trailblazers in gender equality.

Face to face events are planned from April, are we all zoomed out after 2 years?

Zoom has become increasingly unpopular, and I hope we can go back to somewhere near our normal lives. I am worried that although the stats of Covid are decreasing, they are still worryingly high. On April 21st we are going back to Browns Courtrooms to restart our lunches with keynote speaker James Timpson who’ll be talking about kindness in business.

This network is not for ladies who lunch but ladies who work.

A donation comes from each booking going to our work on prison reform.

How did the Robin Corbett Award come about?

After a loved one dies, people gather around giving you sympathy and many cups of tea. A few weeks after the funeral they seem to think you will be able to manage but it is then that you are at your lowest. It was at this point that inspiration struck. As I mentioned before, the sentence I heard on TV: “All men die but some men live on.” was a eureka moment making me decide that I wanted Robin’s legacy to live on.

The Robin Corbett Award celebrates, supports, and rewards the best in prisoner re-integration programmes. Each year we donate funds to three charities, social enterprises or CICs whose mission is centred around giving returning citizens a chance to reintegrate back into society. The presentation is at the House of Lords.

The Robin Corbett Award for Prisoner Re-Integration was established by members of Lord Corbett’s family in conjunction with the Prison Reform Trust in 2013. It is now administered by The Corbett Foundation, a not-for-profit social enterprise.

What are the criteria to being a member of the Corbett Network?

The Corbett Network is a coalition of charities, social enterprises, community interest companies, non-profit organisations and businesses with a social mission who work with those in prison and after release. (Individuals are not eligible). These decision makers are dedicated to reducing re-offending by helping returning citizens find and keep a job. Some members offer mentoring, coaching, training or education.

How many members are there?

Currently there are 108 with four waiting to be introduced to their fellow members.

This network has expanded rapidly over the last few years, is this due to prison reform taking a greater platform?

Once the Robin Corbett Award was established, I kept on meeting people working in their own small pond, so to speak. I thought we could crusade better in a sea and invited them to join us. Since then, together we have created a powerful lobbying voice heard at the highest levels of government and recognized by those in the criminal justice sector as a force for change. I do sense that the media tend to focus on the problems.

Where do you see the Corbett Network positioned in the justice arena?

Peter Dawson, Director of the Prison Reform Trust told me that The Corbett Network is the only one of its kind in the UK. It sits alongside the Criminal Justice Alliance and Clinks which concentrate mainly on policing, courts, prisons, probation, and human rights. The Corbett Network are members of both these organisations.

What are your hopes for the future of this network?

To crusade effectively. To effect changes desperately needed in our prison system. To change public perception of people who have been inside – they are not sub- human. Since the Network started in 2017, we now have over 108 members, holding both face-to-face, virtual meetings, conferences and, crucially, encouraging greater collaboration across the work we collectively do. Together, we have created a powerful lobbying voice, heard at the highest levels of government, and recognised by those in the criminal justice sector as a force for change.

“Prisons should not be society’s revenge but a chance to change direction.” Robin Corbett

This interview was published to mark International Women’s Day 2022.

All photos courtesy of Lady Val Corbett. Used with permission.

Should inmates be given phones?

Offenders who maintain family ties are nearly 40% less likely to turn back to crime, according to the Ministry of Justice. With secure mobiles being rolled out in prisons we ask…

Should inmates be given phones?

This was a question posed to me back in November 2021 by Jenny Ackland, Senior Writer/Content Commissioner, Future for a “Real life debate” to be published in Woman’s Own January 10th 2022 edition.

Below is the complete article, my comments were cut down slightly, as there was a limited word count and reworked into the magazine style.

Communication is an essential element to all our lives, but when it comes to those incarcerated in our prisons, there is suddenly a blockage.

Why is communication limited?

It is no surprise that mobile phones can serve as a means of continuing criminal activity with the outside world, as a weapon of manipulation, a bargaining tool, a means of bullying or intimidation.

But what many forget is that prison removes an individual from society as they know it, with high brick walls and barbed wire separating them from loved ones, family, and friends.

There is a PIN phone system where prisoners can speak with a limited number of pre-approved and validated contacts, but these phones are on the landings, are shared by many, usually in demand at the same time and where confidentiality is non-existent. This is when friction can lead to disturbances, threats, and intimidation.

Some prisons (approx 66%) do have in-cell telephony, with prescribed numbers, monitored calls and with no in-coming calls.

Why do some have a problem with this?

We live in an age of technology, and even now phones are seen as rewarding those in prison.

If we believe that communication is a vital element in maintaining relationships, why is there such opposition for prisoners?

In HM Chief Inspector of prisons Annual report for 2020, 71% of women and 47% of men reported they had mental health issues.

Phones are used as a coping mechanism to the harsh regimes, can assist in reducing stress, allay anxiety and prevent depression.

Let’s not punish further those in prison, prison should be the loss of liberty.

Even within a prison environment parents want to be able to make an active contribution to their children’s lives. Limiting access to phones penalises children and in so doing punishes them for something they haven’t done. They are still parents.

Who watches the Watchdog?

The website for the Independent Monitoring Board (IMB) states:

“Inside every prison, there is an Independent Monitoring Board (IMB) made up of members of the public from all walks of life doing an extraordinary job!

You’ll work as part of a team of IMB volunteers, who are the eyes and ears of the public, appointed by Ministers to perform a vital task: independent monitoring of prisons and places of immigration detention. It’s an opportunity to help make sure that prisoners are being treated fairly and given the opportunity and support to stop reoffending and rebuild their lives.”

Anyone can see this is a huge remit for a group of volunteers.

IMB’s about us page also states:

“Their role is to monitor the day-to-day life in their local prison or removal centre and ensure that prisoners and detainees are treated fairly and humanely”

Another huge remit.

For those who believe they can make a difference, and I have met a few who have, the joining process is quite lengthy.

Once you have completed the online application form, bearing in mind you can only apply to prisons which are running a recruiting campaign (that doesn’t mean to say there are no vacancies in others) the applicant is then invited for an interview and a tour of the prison.

So, what is wrong with that you may ask?

At this point NO security checks have been done, so literally anyone can get a tour of a prison, ask questions, and meet staff and prisoners.

This is surely a red flag.

And then there is the ‘interview’.

Two IMB members from the prison you have applied to and one from another prison take it turn in asking questions. It is basically a ‘tick box exercise’; I know this because I have been involved myself, sitting on both sides of the table.

It is based on scores, so if you are competent in interviews, you will do well. With IMB boards desperate for members it means that as long as your security check comes through as okay, you will have made it on to the IMB board.

However, no references are required to become a prison monitor. NONE.

A red flag too?

One of the main problems I encountered was that if the IMB board member comes from a managerial background they will want to manage. But the IMB role is about monitoring a prison and not managing it. I have seen where members and staff have clashed over this.

Well done, you made it on to the board, what next?

Back to the IMB website:

“You do not need any particular qualifications or experience, as we will provide all necessary training and support you need during a 12-month training and mentoring period”

The first year is the probationary year where you are mentored, accompanied, and trained. To be accompanied for this period is unrealistic, there are insufficient members having neither the time nor resources to get new members up to speed before they start monitoring.

In addition, induction training can be between 3-6 months after joining and can be said it is at best haphazard.

As reported Tuesday by Charles Hymas and others in The Telegraph newspaper, and citing a set-piece statement from the MOJ press office, “a spokesman said that although they had unrestricted access, they were given a comprehensive induction…”

I beg to differ; the induction for IMB board members is hardly comprehensive.

I believe this needs to change.

For such an essential role, basic training must take place before stepping into a prison. Yes, you can learn on the job but as we have seen recently, IMB members are not infallible.

Membership of the IMB is for up to 15 years which leads to culture of “we’ve always done it this way”, a phrase all too often heard, preventing new members from introducing fresh ideas.

What if something goes wrong?

Not all IMB members have a radio or even a whistle or any means of alerting others to a difficult situation or security risk. If for any reason you need support from the IMB Secretariat, don’t hold your breath.

The secretariat is composed of civil servants, MOJ employees, a fluctuating workforce, frequently with no monitoring experience themselves who offer little or no assistance. I know, I’ve been in that place of needing advice and support.

What support I received was pathetic. Even when I was required to attend an inquest in my capacity as a IMB board member no tangible help was provided and I was told that IMB’s so-called ‘care team’ had been disbanded.

From the moment you pick up your keys, you enter a prison environment that is unpredictable, volatile and changeable.

As we have seen this week, an IMB member at HMP Liverpool has been arrested and suspended after a police investigation where they were accused of smuggling drugs and phones into prison.

This is not surprising to me and may be the tip of the iceberg. IMB board members have unrestricted access to prisons and prisoners. As unpaid volunteers they are as susceptible to coercion as paid prison officers.

Radical change needs to be put in place to tighten up scrutiny of, and checks on, members of the IMB when they visit prisons either for their board meetings or their rota visits.

In 4 years of monitoring at HMP/YOI Hollesley Bay I was never searched, and neither was any bag I carried. In over 10 years of visiting prisons, I can count on one hand, with fingers to spare, the number of times I have been searched. When visiting a large scale prison such as HMP Berwyn I only had to show my driving licence and the barriers were opened.

Whilst the situation at HMP Liverpool is an ongoing investigation and whilst the outcome of the investigation is not yet known, I do urge Dame Anne Owers, the IMB’s national Chair, to look urgently at the IMB recruitment process, at the IMB training and at the provision of on-going support for IMB board members.

Complacency has no part in prisons monitoring.

~

Guest blog: Being visible: Phil O’Brien

An interview with Phil O’Brien by John O’Brien

Phil O’Brien started his prison officer training in January 1970. His first posting, at HMDC Kirklevington, in April 1970. In a forty-year career, he also served at HMP Brixton, HMP Wakefield, HMYOI Castington, HMP Full Sutton, HMRC Low Newton and HMP Frankland. He moved through the ranks and finished his public sector career as Head of Operations at Frankland. In 2006, he moved into the private sector, where he worked for two years at HMP Forest Bank before taking up consultancy roles at Harmondsworth IRC, HMP Addiewell and HMP Bronzefield, where he carried out investigations and advised on training issues. Phil retired in 2011. In September 2018, he published Can I Have a Word, Boss?, a memoir of his time in the prison service.

John O’Brien holds a doctorate in English literature from the University of Leeds, where he specialised in autobiography studies.

You deal in the first two chapters of the book with training. How do you reflect upon your training now, and how do you feel it prepared you for a career in the service?

I believe that the training I received set me up for any success I might have had. I never forgot the basics I was taught on that initial course. On one level, we’re talking about practical things like conducting searches, monitoring visits, keeping keys out of the sight of prisoners. On another level, we’re talking about the development of more subtle skills like observing patterns of behaviour and developing an intimate knowledge of the prisoners in your charge, that is, getting to know them so well that you can predict what they are going to do before they do it. Put simply, we were taught how best to protect the public, which includes both prisoners and staff. Those basics were a constant for me.

Tell me about the importance of the provision of education and training for prisoners. Your book seems to suggest that Low Newton was particularly successful in this regard.

Many prisoners lack basic skills in reading, writing and arithmetic. For anyone leaving the prison system, reading and writing are crucial in terms of functioning effectively in society, even if it’s only in order to access the benefits available on release.

At Low Newton, a largely juvenile population, the education side of the regime was championed by two governing governors, Mitch Egan and Mike Kirby. In addition, we had a well-resourced and extremely committed set of teachers. I was Head of Inmate Activities at Low Newton and therefore had direct responsibility for education.

The importance of education and training is twofold:

Firstly, it gives people skills and better fits them for release.

Secondly, a regime that fully engages prisoners leaves less time for the nonsense often associated with jails: bullying, drug-dealing, escaping.

To what extent do you believe that the requirements of security, control and justice can be kept in balance?

Security, control, and justice are crucial to the health of any prison. If you keep these factors in balance, afford them equal attention and respect, you can’t be accused of bias one way or the other.

Security refers to your duty to have measures in place that prevent escapes – your duty to protect the public.

Control refers to your duty to create and maintain a safe environment for all.

Justice is about treating people with respect and providing them with the opportunities to address their offending behaviour. You can keep them in balance. It’s one of the fundamentals of the job. But you have to maintain an objective and informed view of how these factors interact and overlap. It comes with experience.

What changed most about the prison service in your time?

One of the major changes was Fresh Start in 1987/88, which got rid of overtime and the Chief Officer rank. Fresh Start made prison governors more budget aware and responsible. It was implemented more effectively at some places than others, so it wasn’t without its wrinkles.

Another was the Woolf report, which looked at the causes of the Strangeways riot. The Woolf report concentrated on refurbishment, decent living and working conditions, and full regimes for prisoners with all activities starting and ending on time. It also sought to enlarge the Cat D estate, which would allow prisoners to work in outside industry prior to release. Unfortunately, the latter hasn’t yet come to pass sufficiently. It’s an opportunity missed.

What about in terms of security?

When drugs replaced snout and hooch as currency in the 1980s, my security priorities changed in order to meet the new threat. I had to develop ways of disrupting drug networks, both inside and outside prison, and to find ways to mitigate targeted subversion of staff by drug gangs.

In my later years, in the high security estate, there was a real fear and expectation of organised criminals breaking into jails to affect someone’s escape, so we had to organise anti-helicopter defences.

The twenty-first century also brought a changed, and probably increased, threat of terrorism, which itself introduced new security challenges.

You worked in prisons of different categories. What differences and similarities did you find in terms of management in these different environments?

Right from becoming a senior officer, a first line manager at Wakefield, I adopted a modus operandi I never changed. I called it ‘managing by walking about’. It was about talking and listening, making sure I was there for staff when things got difficult. It’s crucial for a manager to be visible to prisoners and staff on a daily basis. It shows intent and respect.

I distinctly remember Phil Copple, when he was governor at Frankland, saying one day: “How do you find time to get around your areas of responsibility every day when other managers seem tied to their chairs?” I found that if I talked to all the staff, I was responsible for every day, it would prevent problems coming to my office later when I might be pushed for time. Really, it was a means of saving time.

The job is the same wherever you are. Whichever category of prison you are working in, you must get the basics right, be fair and face the task head on.

The concept of intelligence features prominently in the book. Can you talk a bit about intelligence, both in terms of security and management?

Successful intelligence has always depended on the collection of information.

The four stages in the intelligence cycle are: collation, analysis, dissemination and action. If you talk to people in the right way, they respond. I discovered this as soon as I joined the service, and it was particularly noticeable at Brixton.

Prisoners expect to be treated fairly, to get what they’re entitled to and to be included in the conversation. When this happens, they have a vested interest in keeping the peace. It’s easy to forget that prisoners are also members of the community, and they have the same problems as everyone else. That is, thinking about kids, schools, marriages, finances. Many are loyal and conservative. The majority don’t like seeing other people being treated unfairly, and this includes prisoner on prisoner interaction, bullying etc. If you tap into this facet of their character, they’ll often help you right the wrongs. That was my experience.

Intelligence used properly can be a lifesaver.

You refer to Kirklevington as an example of how prisons should work. What was so positive about their regime at the time?

It had vision and purpose and it delivered.

It was one of the few jails where I worked that consistently delivered what it was contracted to deliver. Every prisoner was given paid work opportunities prior to release, ensuring he could compete on equal terms when he got out. The regime had in place effective monitoring, robust assessments of risk, regular testing for substance abuse and sentence-planning meetings that included input from family and home probation officers.

Once passed out to work, each prisoner completed a period of unpaid work for the benefit of the local community – painting, decorating, gardening etc.

There was excellent communication.

The system just worked.

The right processes were in place.

To what extent do you feel you were good at your job because you understood the prisoners? That you were, in some way, the same?

I come from Ripleyville, in Bradford, a slum cleared in the 1950s. Though the majority of people were honest and hardworking, the area had its minority of ne’er-do-wells. I never pretended that I was any better than anyone else coming from this background.

Whilst a prisoner officer under training at Leeds, I came across a prisoner I’d known from childhood on my first day. When I went to Brixton, a prisoner from Bradford came up to me and said he recognised me and introduced himself. I’d only been there a couple of weeks. I don’t know if it was because of my background, but I took an interest in individual prisoners, trying to understand what made them tick, as soon as I joined the job.

I found that if I was fair and communicated with them, the vast majority would come half way and meet me on those terms. Obviously, my working in so many different kinds of establishments undoubtedly helped. It gave me a wide experience of different regimes and how prisoners react in those regimes.

How important was humour in the job? And, therefore, in the book?

Humour is crucial. Often black humour. If you note, a number of my ex-colleagues who have reviewed the book mention the importance of humour. It helps calm situations. Both staff and prisoners appreciate it. It can help normalise situations – potentially tense situations. Of course, if you use it, you’ve got to be able to take it, too.

What are the challenges, as you see them, for graduate management staff in prisons?

Credibility, possibly, at least at the beginning of their career. This was definitely a feature of my earlier years, where those in the junior governor ranks were seen as nobodies. The junior governors were usually attached to a wing with a PO, and the staff tended to look towards the PO for guidance. The department took steps to address this with the introduction of the accelerated promotion scheme, which saw graduate entrants spending time on the landing in junior uniform ranks before being fast-tracked to PO. They would be really tested in that rank.

There will always be criticism of management by uniform staff – it goes with the territory. A small minority of graduate staff failed to make sufficient progress at this stage and remained in the uniform ranks. This tended to cement the system’s credibility in the eyes of uniform staff.

Were there any other differences between graduate governors and governors who had come through the ranks?

The accelerated promotion grades tended to have a clearer career path and were closely mentored by a governor grade at HQ and by governing governors at their home establishments and had regular training. However, I lost count of the number of phone calls I received from people who were struggling with being newly promoted from the ranks to the governor grades. They often felt that they hadn’t been properly trained for their new role, particularly in relation to paperwork, which is a staple of governor grade jobs.

From the point of view of the early 21stC, what were the main differences between prisons in the public and private sectors?

There’s little difference now between public and private sector prisons. Initially, the public sector had a massive advantage in terms of the experience of staff across the ranks. Now, retention of staff seems to be a problem in both sectors. The conditions of service were better in the public sector in my time, but this advantage has been eroded. Wages are similar, retirement age is similar. The retirement age has risen substantially since I finished.

In my experience, private sector managers were better at managing budgets. As regards staff, basic grade staff in both sectors were equally keen and willing to learn. All that staff in either sector really needed was purpose, a coherent vision and support.

A couple of times towards the end of your book, you hint at the idea that your time might have passed. Does your approach belong to a particular historical moment?

I felt that all careers have to come to an end at some point and I could see that increasing administrative control would deprive my work of some of its pleasures. It was time to go before bitterness set in. Having said that, when I came back, I still found that the same old-fashioned skills were needed to deal with what I had been contracted to do. So, maybe I was a bit premature.

My approaches and methods were developed historically, over the entire period of my forty-year career. Everywhere I went, I tried to refine the basics that I had learned on that initial training course.

Thank you to John O’Brien for enabling Phil to share his experiences.

~

A conversation with: Phil Forder

I was delighted when Phil Forder agreed for me to interview him. There is always a lot more to a person than their job so I wanted to learn more about him. When I asked why he agreed, he responded:

“Because you are a speaker of truth”

So, who is Phil Forder?

“My job title is community engagement manager at HMP Parc but as you so rightly said previously. ‘There is more to an individual than their job.’ I’m also a painter writer and woodcarver. LGBT rights supporter. Environmentalist Nature lover. Lecturer, etc. “

But in a nutshell

“Just a bloke doing what I think is right and enjoy doing”

One thing we have in common is our association with Suffolk, I believe you were born there?

“I moved from Suffolk at 3 weeks old. Mum and Dads parents were from Suffolk, we then moved to Somerset and to Harlow in Essex where I grew up. I am one of six children.

Just before lockdown, I found the time to go through my mum’s memories she had written down before she passed away.

Mum grew up as a child in Beccles, Suffolk. Working class, brought up in the country before 2nd World War.

Grandfather prisoner of war in Germany, but never spoke about it.

Dad was a strict Catholic and worked at Downside Abbey, in Somerset and whilst there trained in teaching.”

“We moved to Harlow on the outskirts of London, in limbo between two worlds and was voted as the 2nd most boring place in British Isles.”

But Living in Essex Phil felt excluded because of his sexuality and tried to avoid facing up to it.

Whilst searching for his own identity and a way of fitting in somewhere and searching for a way out of Harlow, he decided to train to be a priest, but 3 months later he realised that was not the direction for him.

Before college Phil hitched to Afghanistan then blagged his way into Art college without an interview even though he had failed most of his exams. During his time, he managed to get a sabbatical and hitchhiked a second time to Kashmir.

Was he running away again?

But the problem is you can’t run away from self.

Back to Art college to finish his course and was voted Student of the Year.

He decided to live in isolation in a caravan and worked in a wholefood shop and then was promoted to managing it. But still there was a struggle within as to who he really was and what he should do in life.

There were many changes in the pursuing years including being a father, wanting a different kind of education for his child led to home-schooling and eventually attendance at an alternative Steiner School. This somewhat alternative way of educating was based on the idea that a child’s moral, spiritual and creative sides need as much attention as their intellect.

Helping out in Kindergarten as an assistant influenced Phil to train as a Steiner teacher in alternative education.

“But after 8 years, I wanted to do something completely different”

“A friend who was a magistrate phoned me up and said there was a job going as an Art teacher at HMP/YOI Parc, talk about a baptism of fire”

Such a contrast from working in a nurturing environment where parents cared for their children, were financially secure and where children grew up in a healthy environment.

He was then faced with dysfunctional families reminding him of his upbringing in Harlow that he had fought so hard to leave behind.

“Many of the lads in the YOI had known poverty, had mental health problems, history of abuse, came from dysfunctional families, history of crime in their family, history of substance misuse in their family and had poor education”

“Look what they were born into, their formative years. These young men then become society’s problem by falling through every net and ending up in prison”

Phil’s job changed when he became Equalities Manager and as he aptly said to me:

“To make an impression on a person you have to work with them and not against them.”

He developed a course to help the inmates engage and address their behaviour as most courses focus on what is wrong with them. But some are so ashamed of what they have done they cannot talk about it or even admit it. Phil wanted them to focus on what was good about themselves, what they had achieved, and only then when in a position of strength and comfortable can you tackle some of the issues.

“I brought a three day course into prison “The Forgiveness Project” founded by Marina Cantacuzino. It’s an amazing course, it’s important to put yourself with the prisoners and teach by example”

In addition:

“I joined the Sports Council for an equalities point of view and invited a gay football club (Cardiff Dragons) and a gay rugby team (Swansea Vikings) to play against the prisoners. I wanted to break down stereotypes”

Who has inspired you?

“One of the most influential person has been Barbara Saunders Davis, her life very much influenced by Rudolf Steiner, came from an aristocratic family having studied in Paris and lived on her estate in Pembrokeshire. She taught me self-worth, life, Rudolph Steiner and anthroposophy (a philosophy based on the teachings of Rudolf Steiner (1861–1925) which maintains that, by virtue of a prescribed method of self-discipline, cognitional experience of the spiritual world can be achieved) I was honoured at her funeral to read the eulogy”

In your Twitter bio you have an impressive list apart from your work. Can you expand on some of these?

Author

“In 2015, I wrote a book “Inside and Out”, a compilation of writings from LGBT people within HMP/YOI Parc, both prisoners and staff alike”

https://menrus.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Inside-and-out-2015.pdf

This book was featured in the Guardian in an interview by Erwin James.

His boss at HMP Parc, director Janet Wallsgrove, expressed pride in what Phil and his colleagues achieved.

“This book is a statement,” she says.

“It’s saying that we at Parc recognise and support everyone’s right to be respected as an individual. It’s both about tackling homophobia and challenging people who express views that are unacceptable and about getting people to feel comfortable with themselves and more motivated to buy into a rehabilitative culture in prison and in society.”

Another book Phil wrote was:

Coming out: LGBT people lift the lid on life in prison: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2015/aug/12/lgbt-people-prison-struggle-book

Painter

“When I first started working in the prison, I realised there was no art available on the Vulnerable Prisoners Unit. As there was no classroom available, I taught art on the wing, with up to 30 men although resources were scarce”

Lecturer

“Over the years I have been asked to lecture on various aspects of prison life mainly to do with LGBT in prisons”

Trustee

“I am a trustee of two charities, the first FIO a theatre company that tells stories that are or would otherwise go untold or unheard

and the second is the Ruskin Mill Education Trust for young people with learning difficulties.”

The last words go to Marina Cantacuzino:

“In the 10 years I was closely involved with several prisons in England and Wales I met three exceptional staff members who worked far and beyond what was expected of them, and were responsible for supporting charities like The Forgiveness Project to deliver their programmes to help change prisoners’ lives. The other two people burnt out – and left the prison service but Phil is still there! He seems to have reinvented himself a couple of times but his complete dedication to supporting prisoners is I think unprecedented. I don’t know what it is about him – is it his sense of humour, his deep creative/artistic streak, his compassion, his humanity, all of this! – that allows him to continue and keep doing outstanding work in this field. I now follow his progress on Twitter but for a long time he was our mainstay in Parc prison – the person who brought in the RESTORE programme and ensured it continued even when he was no longer in charge of this area. A wonderful human being!”

Thank you, Phil.

~

Photo credit: contributed by Phil Forder

On this day the only April fools are my critics: Part 2

It is 4 years today that I put pen to paper and wrote about the Independent Monitoring Board (IMB) from my direct experience and my perspective as a prison monitor. My article “Whistle blower without a whistle” published in The Prisons Handbook 2016, sent shock waves across the criminal justice sector, locally, nationally and internationally.

When you feel so passionately about a cause it is very hard to keep quiet, I couldn’t stay quiet any longer. I was given the opportunity and used my voice.

First, I had to weigh up the risk of possibly causing offence versus the need to speak up in the public interest.

What I didn’t expect was it resulting in a prejudicial character assassination, a fight to clear my name, being gagged by a grooming culture within the IMB, being investigated twice by UK Ministry of Justice, a disciplinary hearing at Petty France and the involvement of not one but two Prison Ministers. I felt that I was on my own against a bastion of chauvinism. Not the last bastion of their kind I would come across. Welcome to the IMB!

Maybe the problem was that the IMB and the MoJ didn’t expect someone like me to put their head above the parapet or to dare voice an opinion. Yet we all have a voice; we all have opinions and we should not feel the need to suppress them. I did, I felt that I couldn’t really express myself, would anyone listen?

Faced with adversity, people either ‘fight, flight or play dead’. I made the decision to fight. I have no regrets.

People started listening, taking notice and lending their support. Above all, they agreed with me but felt unable to say anything publicly themselves for fear of reprisals.

We all know the saying ‘action speaks louder than words’ but often you have to speak before any action can take place. So, I spoke out and expected results.

Since then I have written on many occasions about the IMB, its lack of effectiveness, lack of diversity and most troubling of all its lack of independence. The IMB Secretariat is staffed by MoJ civil servants, the National Chair is an MoJ employee, the purse strings are held by the Permanent Secretary of the MoJ and Board members expenses are paid by the MoJ.

“I’m finding the working environment intolerable and detrimental to my health, and part of me would like the IMB to recognise this as a symptom of its unsustainable system and the pressure it puts on people (but they probably won’t care)”.

Sadly, when I continue to receive messages such as this one from a serving IMB Chair, I realise very little has changed.

Unchanging. Unchangeable.

Even with a new governance structure, the appointment of its first National Chair and a written protocol between the MoJ and the IMB, none of these has persuaded me that there is enough independence, effectiveness or impact.

If there are concerns and issues that don’t add up, instead of staying silent, ignoring the facts or even dismissing them, it is imperative to ask questions.

As I have seen first-hand with the relationship between the IMB and the MoJ where they appear to be marking their own homework where monitoring of prisons is concerned, I noticed another irregularity.

During 2019 whilst attending sessions of the All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Miscarriages of Justice, I noticed something of vital importance about the composition and scope of the inquiry of the Westminster Commission on Miscarriages of Justice, which states:

“Given that there are serious misgivings expressed in the legal profession, and amongst commentators and academics, about the remit of the Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC) and its ability to deal with cases of miscarriages of justice, and given that perceptions of injustice within the criminal justice system are as damaging to public confidence as actual cases of injustice, the WCMJ will inquire into:

1. The ability of the CCRC, as currently set up, to deal effectively with alleged miscarriages of justice;

2. Whether statutory or other changes might be needed to assist the CCRC to carry out is function, including;

(i) The CCRC’s relationship with the Court of Appeal with particular reference to the current test for referring cases to it (the ‘real possibility’ test);

(ii) The remit, composition, structure and funding of the CCRC

3. The extent to which the CCRC’s role is hampered by failings or issues elsewhere in the criminal justice system;

and make recommendations.”

But between 2010 and March 2014 Dame Anne Owers who currently sits on the Westminster Commission on Miscarriages of Justice “established by the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Miscarriages of Justice (APPGMJ) with a brief to investigate the ability of the criminal justice system to identify and rectify miscarriages of justice”, was a non-executive director of the CCRC.

Public purse. Public interest.

I have a problem with a system that allows for a person to occupy a role paid for from the public purse who then later occupies a separate post, albeit as a volunteer with expenses paid from the public purse, which is meant to scrutinise the work that has been done previously by that same person.

This is utterly incompatible because of the risk that the full truth of what was done or was not done previously may never see the light of day. I believe it is in the public interest to ensure that officials never get the opportunity to mark their own homework. This is especially true when it comes to the substantive issues of miscarriages of justice.

We are talking about miscarriages of justice. We are talking about lives that have been ruined. We are talking about lives which have been lost and about families that no longer have their loved ones.

Deciding to ask someone with a link to a current CCRC application, whose opinion I trust, if they would see the APPG on Miscarriages of Justice differently should a member of its commission have had previous links with the CCRC, their response was startling and very revealing:

“I certainly would Faith. A commission looking at the inner workings and efficiency of the CCRC should be totally independent looking at the watchdog with open and unclouded eyes. I dread to think which kinds of bias would come into play if somebody with a past association to the CCRC were allowed to be part of the investigatory commission”

Separately, as a friend once said to me:

“Faith has stood her ground where many others have feared to tread and of course I admire this characteristic immensely but more than that, she has survived and continued her quest with renewed vigour”

I am nobody’s fool and the Ministry of Justice has left me with no alternative than to continue to take more robust action in the public interest. This in part means being willing to ask probing questions whenever I discover irregularities in the Criminal Justice System, and fully intend to continue to do so.

~

Credit

Photo is copyright and used with permission.

Erratum

Paragraph 18. “also paid for from the public purse” deleted and replaced with: “albeit as a volunteer with expenses paid from the public purse,”

~