Home » OPCAT

Category Archives: OPCAT

The IPP sentence: At an Inflection Point?

I have followed the Imprisonment for public protection (IPP) issue for over 10 years and seen how political inertia has stifled any chance of reform. But things are now changing. We are at an inflection point. To learn more, I listened to all episodes of the ‘Trapped: The IPP Scandal’ podcast series.

On 25 July 2023 one of its producers, Melissa Fitzgerald, contacted me and invited me to meet their entire team. This led to conducting an interview with two members, Hank Rossi (Consultant) and Sam Asumadu (Investigative Reporter).

10 minute read.

Faith: To what degree have you noticed how the IPP sentence has emerged as a major issue, and could even be stated as a tragedy within our Criminal Justice System?

Sam: I absolutely agree it’s a tragedy in our criminal justice system. Once you’ve done your original tariff, you’re basically being detained on what you might do rather than what you have done. To me, that’s something for science fiction, not a functional society. Preventative detention should not have had any place in British jurisprudence. The IPP sentence was abolished in 2012 on human rights grounds. Because it wasn’t retrospectively abolished, it’s meant that there’s this legacy and hangover of a particular time in British history, from the New Labour government.

Faith: You spoke with Lord Blunkett, was he dismissive or contrite in any way or genuinely mortified by the suffering caused by not only those given an IPP sentence but their families too. Could he have foreseen how this sentence would be implemented?

Sam: It’s hard to comprehend that this is where we are, over 80 people serving an IPP sentence have died in prison taking their own lives, so many people have been broken by what’s happened. Lord Blunkett has been quite vocal about the IPP, he has been contrite, and he has apologised. He does seem to care about the issue, whether that’s a matter of him thinking about his legacy or if it’s completely genuine, I don’t know. I can’t judge what’s in a man’s heart. However, it doesn’t quite matter how contrite he is because it’s still happened and a lot of lives have been destroyed and are still being destroyed, in my opinion. I think he believes that initially, at least, the judges were over applying the sentence to many people. I think it was just very bad legislation on his part and the Ministry’s part. You have to look at what may go wrong, the worst-case scenarios in legislation, because once it is out, it becomes part of bureaucracy, and into people’s hands. People are fallible, especially when it comes to prisons.

Faith: There were alternatives already. He didn’t need to bring in this new legislation.

Sam: He didn’t, but it did look good at the time. It sounded good as well and it was attractive to the people in the government. Finally, we’ll deal with the underclass.

Faith: How do you get beyond any concerns that you may have that your reporting will fall on deaf ears?

Sam: The series is a permanent record of what is an incredible failure of society. I think the authorities can’t hide from it now. We can send questions to Alex Chalk and Damian Hinds to keep pressure up, making sure they know people are watching. They can’t hide from us.

Faith: We are bombarded with messages from the media, be it on social media or in the newspapers. How do you get an audience to not just listen but act too?

Sam: Ultimately, it’s in their hands. We want people to act. What we’ve done is to highlight stories of people who are campaigning family members. They have little to no resources. Listening to that, I hope it makes people feel incumbent that they can do something themselves to help end this horrific tragedy. This could have happened to their family members too.

Faith: As a professional journalist you have an acute sense of right and wrong and fact from fiction. But has the topic of IPP gripped you because of any reason other than justice v injustice?

Sam: I can’t believe that the state thinks that they can keep on saying it’s “a stain on the British justice”, “stain on the conscience of the British Justice” and not rectify it. The state has a duty to care for prisoners whether they like it or not. Yet people have died and are dying on their watch. And I think that there should be some sort of accountability for that.

Faith: I understand prior to these podcasts, you were involved in a piece of research around IPPs with the Centre for Crime and Justice Studies (CCJS). Can you outline the part you played?

Hank: I funded Zinc Productions and we’ve hired Steve, Melissa, and Samantha to do this work. We’ve worked with quite a lot of the families and friends of IPP’s and with a number of IPP sentenced individuals as well. I started a process with the researchers at the Centre for Crime and Justice Studies (CCJS) in 2020. I approached them, having approached a number of criminal justice reform charities about this issue to fund some research on the possibility of an independent tribunal on IPP. Every time I looked further into this, I got more concerned. I almost, you know, started to become unwell myself, thinking this can’t be real.

One of the processes that I thought might help, was a sort of tribunal inquiry when power cannot hold itself to account because of nefarious activities of those who have it. You can get a group of citizens together and hold your own inquiry. That’s what I thought might be a useful way to look at the problems of IPP. Richard Garside and Roger Grimshaw from CCJS sat around the table with me and we came up with a plan to research the idea for an independent People’s Tribunal on indeterminate detention in the UK. That led to a document I was signing to invest some money in their work to research this idea.

I was sort of feeling like we’d achieved something just by having a conversation when so many people, organisations, and people in power were unwilling to talk about it. Richard and Roger took this seriously at the CCJS and we signed an agreement. The very next day, out of the blue, the government was going to be put under the spotlight by the Justice Select Committee as they launched their inquiry into IPPs.

Faith: Do you believe we live in a punitive society, which has then led to one of the flaws in the IPP sentence as assessing the dangerousness of each offender?

Hank: The short answer is yes. We live in a far too punitive society. I’ve just come across a document published by the Prison Reform Trust in 2003 where the writers are looking at sentence length and they’re worried that they are getting longer. Since then, we’ve gone to this extraordinary place now where a whole life tariff is an everyday thing. I call it the punitive ratchet. We are now learning about the significant harm that prison does to an individual. That’s perhaps what I would say about the punitive concept of prison. The way that we engage with it in the United Kingdom is toxic and has become more and more toxic in the 20 years since the millennium.

Assessing Dangerousness is a complex and very difficult business. You could argue that the assessments tools are inherently problematic because of the nature of prediction. That is a fundamental flaw in the idea of the IPP legislation in the first place to think that there was a system that you could implement to usefully predicts people’s behaviour in the future. And initially the whole process of IPP sentencing circumvented assessment for many. They were just labelled as dangerous based on the offence.

Faith: If you talk about dangerousness, this has changed throughout the sentence.

Hank: This is what annoys me endlessly about the fall back of “Oh, well, this person was a dangerous individual”, no, they weren’t necessarily in many of the cases. There is no evidence to me that people can be predictably relied upon to do the same thing in the future. You can say what a statistical likelihood is but that is nowhere near the same as knowing what someone will do. And we know that from the statistics, less than 1% of people go on to commit a serious further offence when they’ve been out of prison.

Faith: Is the IPP sentence a systemic miscarriage of justice?

Hank: Yes, that’s the best short description of it. Some people would say this is not a miscarriage of justice because that requires an individual to have been completely misrepresented in the process. There’s a researcher who calls these sort of events “errors of justice”. In other words, they are less clear. And there’s truth that these people who committed an offence should be punished by a prison sentence. How long they spend in jail should be part of that process. The idea of indefinite detention, that’s a no no. In international law, we shouldn’t do that.

Faith: With the pressure mounting for Alex Chalk the Secretary of State for Justice to act, how hopeful are you that there will finally be a breakthrough?

Hank: I am hopeful. There is action that people are taking and movement in the system. It’s a systemic problem, and what I know about systems theory is that you might have to take multiple approaches to shift a problem in a system. Unfortunately, when people say, well, how do you fix that? they say, well, you have to go through the legislative body and that’s our parliament. And parliament is a complicated place.

Alex Chalk is in the hot seat right now, and I know he’s really feeling it. There are things he could do tomorrow through LASPO (Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012) to make this go away using executive powers. He’s chosen not to use those at this point. We’ll see if there’s continuing pressure from campaigners and from international bodies. Maybe he will be pushed to do more. But the problem is that under international law, this must be looked at on a case-by-case basis. Well, there’s 3000 people in prison to consider on a case-by-case basis. It’s a nightmare. So, we need some executive action. But I have a feeling that things will happen.

Following on from what Sam was saying, I agree this is the most egregious example of state violence I’ve come across in the UK in my lifetime. I’m over 50 years old. People have been persecuted in a way that I’ve never imagined in this country. The IPP sentence is toxic. It’s extraordinary that the system we have has not been able to rectify that. It leads me to believe that we have a very weak parliamentary democracy. Essentially the power of the executive to keep this going when it should not keep going, is too much. There’s something going wrong within the structure with the roles and the regulations of how parliament and our democracy work.

One thing that I’ve concluded is instrumental perhaps, and was talked about 15 years ago, was the merging of the role of the Lord Chancellor with the role of the Minister of Justice, When that job was boiled down into one, you end up with a problem of separation of powers, I think. And that’s a fundamental problem. So that’s something for us to think about in the future.

Faith: I had lunch recently with Shirley de’Bono where she shared with me her next step in her campaign for IPP prisoners being released, to go to the United Nations in Geneva to have discussions with Dr Alice Edwards, Special Rapporteur on torture. I believe you went along too.

Hank: I’ve been communicating and collaborating with quite a number of different people in different organisations, and I wasn’t expecting to be invited. In the week before a meeting was set up, I was invited to attend in Geneva with Dr. Alice Edwards and Shirley de’Bono and others, and the conversation was about what is going on and what might be done. Shirley presented several cases. I mean, just this is a horror show, isn’t it? You can’t make it up. I’m as worried about this as I have been about anything in my life. I lose sleep over this. And I think that this is an important moment. In Geneva more information was sought by the Special Rapporteur and indications were given that statements will be made in the future that perhaps will certainly shame the United Kingdom’s government on the international stage.

Faith: Do you think the UK government should take any notice of the United Nations, and if so, how much pressure should the United Nations place on the UK government?

Hank: The United Kingdom being a signatory to the Optional Protocol on the Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (OPCAT) is a powerful thing. We’ve agreed to do certain things to honour certain international standards, and we’re not doing that. And the fact that this hasn’t been noticed for a decade is shocking. But going back to the torture problem, the United Nations has clear guidelines on this. We’re breaking many of them.

The United Nations doesn’t have legal or legislative making powers, but it has influence. On 30th of August the United Nations special rapporteur on torture made a statement condemning this situation. I believe they’ve sent a letter to our government and their response will have to have sent in before the 23rd of November, when we should hear what the letter said. We won’t know until then perhaps exactly what’s going on, but it’s all very useful in putting pressure on our government.

Faith: In your opinion, should the UK withdraw its signature from OPCAT because the very existence of an IPP sentence, which we know inflicts psychological harm, and psychological harm is a form of torture, does not align with its agreement to OPCAT?

Hank: I think we need to be part of this. And the whole point of mechanisms where someone can criticise you is useful. In some organisations you create a specific chain of responsibilities and it’s often known as “just culture” where whistleblowing is encouraged, and recriminations are not expected if someone highlights a concern. But in this system, we’ve have had the opposite, that the snuffing out of criticism and the silencing of objections has been part of why this has gone on so long. And that’s got to stop. The National Preventative Mechanism (NPM) has 21 agencies appointed by our government to fulfil the obligations under OPCAT. These agencies have certain powers and they’re not using them properly. Also, the independence of them is questionable. Is it time for a review of the NPM?

Three years ago, I introduced the idea of a people’s tribunal on indefinite detention to the Centre for Crime Justice Studies. We’ve weighed up whether there was any need for a tribunal process, if the Justice Committee made these very strong recommendations that change was needed, of course that’s very positive. But what we’ve found is that the government is not interested, and Parliament seems to have gone along with it. There are indications there’s going to be a bit of noise in Parliament about the Victims and Prisoners Bill. The international community are now waking up like a sleeping giant and the possibility of an independent process to hold government to account and to make a record of the situation is still an idea.

Using Disaster Incubation Theory, we can look at this crisis as an unfolding sequence of events, which was almost predictable. Baron Woolf, former Lord Chief Justice, made comments to Lord Blunkett before IPP legislation was enacted that this was a terrible idea. Blunkett claims not to remember the criticism of it, he went ahead and did it anyway. And look what happened. And you know, people have predicted this crisis.

However, one of the biggest problems of prediction is complexity and you can’t just keep people in prison because you think that something might happen in the future.

Faith: Initially an IPP sentence was to be imposed where a life sentence was inappropriate, so where did it go wrong?

Hank: Indefinite detention induces desperation; this is known from psychological research. Induced desperation is a form of psychological torture. There’s plenty of evidence to show that you don’t need more than a couple of weeks having desperation induced in you by this type of prison sentence to suffer mental health consequences. Suicidal ideation, depression, all of these things we hear about over and over again. It’s extraordinary that more people haven’t managed to take their own lives. So, imagine there’s a system which is inducing you to feel suicidal and then to sort of trap you in a suspended animation forever where you can’t kill yourself because they’ve taken away all of the facility for you to do that, but continue to indefinitely detain you. That is like a horror movie. We talk about the “psychological harms” of this, but it is absolutely punishing.

Faith: How has it got to this point where you’ve got so many people dying on a sentence? How has it been allowed?

Hank: It continues for political reasons. These are essentially political prisoners caught in a situation which is way beyond the norm and the political climate is such that it’s very difficult for someone to do something publicly about it. I suspect change may happen quietly in the near future, there will be moves to influence what happens at the parole board hearing, at the prison gate and what happens in various sorts of quiet corners of the system in order to expedite the release of these people while the international community waves its fist at us.

Faith: Bernadette’s story (Episode 6) highlights the ambiguous criteria for prisoners diagnosed with Offender Personality Disorder (OPD) and once on this pathway they are labelled. Why do you think this diagnosis is used against IPP prisoners rather than to help them?

Hank: This is an enormous abuse of power. What’s happened here is a shocking scandal. That’s why a tribunal process might be quite useful because since the invention of the Dangerous and Severe Personality Disorder (DSPD) twenty years ago they were constructing a diagnosis out of thin air for the purposes of managing people in a system, in this case processing them through a criminal justice system. The outcome of that is quite toxic, especially when we know that the incarceration of individuals has severe implications on their behaviour. The National Offender Management Service (NOMS) then implemented the Offender Personality Disorder Pathway (OPD) which might be seen again as a bogus system. It’s invented for management of people who are likely to be disruptive because of the nature of how human beings respond in a prison system.

Research by Robert Sapolsky on neuroendocrinology and research by Daniel Stokols, who is an environmental psychologist, suggests that people in prison systems are very likely to misbehave for many reasons if their circumstances result in a reduction of their agency. If you don’t have a strong identity or a strong sense of purpose, and you are subjected to many of the things that are happening currently in our prison system, you’re very likely to have people starting to suffer mental illness.

Sam: I think most IPP prisoners say I understand my original sentence and the original tariff. It’s what’s happened beyond there I can’t get to grips with and why I’m so distressed by it all. So, I don’t think it’s like shirking responsibility. They do say, okay, fine, I did what I did. Maybe I deserved custodial, but this is beyond what ever should happen to a human being.

Faith: As the OPD Pathway was originally designed for problematic prisoners, do you see any logic in 96% of all IPP’s are given this diagnosis?

Hank: It is cruelty beyond belief. Well, you’re going to be causing trouble if you feel you are being tortured, you’re going to become problematic.

Faith: With Bernadette’s partner, there seems to be little understanding or consideration of how he would struggle when medication for bipolar was withdrawn as a result of a new diagnosis of OPD. Do you see this as a cost-cutting exercise or something else more sinister? Where is the duty of care?

Sam: I think maybe they started with the intentions of cost cutting, this whole sort of merry go round of people being sent to psychiatric hospitals. They thought they could keep it inhouse and that they could label people with personality disorders and keep them inside these NHS units. But then what has happened is that it has become a tool to cage problematic prisoners which people on an IPP sentences will be just because of the nature of what’s happening to them. IPP related distress is not factored in with the OPD pathway, including at parole as we see.

I won’t use the word sinister, but it does feel like it was a way to preventively detain these people. By labelling them as having a personality disorder, or offender personality disorder, which we know is made up.

Faith: The provision of medication or the lack of medication should be a clinical decision and yet it is left to non-clinical staff to determine. Where do you think this failure originates and who is to blame?

Sam: I don’t know the answer to this question. I guess there’s a lot of bureaucracy that comes into this. I think it’s you who said to me that sometimes, prisoners move from prison to prison and their files don’t catch up with them. Then the prison staff don’t even know that they’re supposed to have medication at this time.

Hank: Clinical decisions should be made by doctors. The whole thing with, DSPD and the OPD where clinicians are left out, how can that make sense? Well, one of the reasons is there aren’t enough clinicians working in the system. This prison system creates mental health problems. It’s a double crisis.

Faith: Those in prison should get the same level of health care in prison.

Hank: Well, I have heard some anecdotal stories, some people have said that it’s hard to get mental health support outside prison, they have had better sort of conversations inside prison. It is hit and miss.

Someone who worked in a general hospital told me that the psychology services were downplaying people’s conditions because they knew they couldn’t provide resources to help them. Psychological assessments were being downgraded in the sense that if someone came in and they hadn’t actually tried to commit suicide, but were expressing suicidal thoughts, they were sent home because there was nothing that could be done. That’s extraordinary. That’s just out in the community. And we think the same things happen in prison.

Sam: I really don’t know where to lay the blame on this one. I think in some ways prison governors should have more discretion maybe to help how they deal with their prison.

Faith: In your pursuit of the truth about IPP it appears you have uncovered a further irregularity. In IPP Trapped podcast, Episode 6, Prof Graham Towl, previously Chief Psychologist at Ministry of Justice, says that Dangerous and Severe Personality Disorder (DSPD) was invented not by psychologists but by politicians. This is an astounding revelation.

Sam: The DSPD, a precursor to the IPP, was brought in, in the late nineties. The DSPD and eventually IPP was a way to preventively detain people that they didn’t know what to do with whether that was correct in terms of criminal justice or not.

Faith: Is resentencing the only way to ensure that no one spends the rest of their life in prison despite having not been convicted of an offence of gravity that would warrant life imprisonment or is there some other way?

Hank: The government has re-sentenced people before. Resentencing is the thing that works for justice, but it might be slow, and it may not work well for the emergency that I see. I think this is like a mass casualty situation and it is a crisis with significant humanitarian costs, and it needs to be sorted out quickly. You can’t keep torturing people once you know that that’s what you’re doing. There’s a sort of denial going on amongst the authorities. Re-sentencing is a part of the story, but it might be that there are other things in the nearer term that might be needed to expedite certain people’s recovery. But yes, it’s definitely part of the network of considerations.

Faith: In practical terms how hard is it to change IPP? Must it be legislative change or a judicial change, or a policy and practice change? But in the case of legislation to that end takes time, given the prevalence of self-harm and suicides amongst IPP’s, some don’t have that time.

Sam: I think James Daly MP, often says these people could be in prison 40 years down the line. It sounds incredible, but. Yeah. If nothing is done, it could be 40 years.

Faith: I read that 75% of recalls to prison were IPP’s, yet 73% of these recalls didn’t involve a further offence. Do you think the criteria for recall is too broad?

Hank: Absolutely. This is all about risk aversion. For some reason, IPP’s have been put in this network of problems where risk aversion is of the highest order. Essentially the system assumes that they are the most dangerous people on Earth, and they really aren’t.

The parole board is getting it wrong; the probation service is getting it wrong, the judiciary got it wrong, and the government is getting it wrong. I can’t see any point in the system where they’re getting it right. That’s a frightening thing. We can keep talking about it and we can keep hoping that they will change because the more we talk about it, the less likely they’ll get away with it.

Sam: With recall, there’s the human element of probation officers where they just get things wrong, they are overzealous. One story I heard was someone who had moved address, he’d spoken to his probation officer, and he thought it was approved. A week later, the police collected him from his new address, saying that he breached his license, giving the reason as his change of address. But how did they know the address if the probation officer didn’t tell them? This strange logic that seems to be that the first principle is send them back to prison rather than keeping them in the community and finding the best ways that they can work with them.

Faith: With probation as with prison officers so many have left the profession and you’re left with those with very little experience. You are left with a system run by inexperienced people. So, mistakes will happen.

Hank: Along with the punitive ratchet, the problems in probation are the biggest thing that’s happened in the last 20 years. Everyone’s overloaded. And it’s just a system that’s in crisis again. From the moment you’re arrested for an offence, the police are in crisis, the courts are in crisis, the prisons are in crisis, and the probation service is in crisis. This does not bode well for a quick answer to this. I think this topic should be at the front of the queue for fixing and sorting. The discrimination that someone on an IPP is suffering from where a person who’s committed the same offence, who’s in the same cell or next door who’s getting out after a fixed term, that is discriminatory.

Sam: That’s why they talk about violent offenders when they’re talking about IPP and don’t look at the individual cases. Most cases between 2005 and 2008, were not serious crimes.

Hank: The whole thing is bewildering. I hear myself say “I can’t believe this is happening in our country”, especially a country that used to pride itself on having one of the better criminal justice systems. Other countries model their justice systems on the British system, and it turns out we’ve got the most rotten system around.

Faith: The criminal justice system is in such disarray, isn’t it?

Hank: Despite all the independent monitoring that goes on, it’s very hard to imagine that there’s not a lot more going unreported.

Faith: In your opinion is the current Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice, Rt. Hon Alex Chalk KC MP, going fast enough to resolve IPP in his tenure or will he too run out of road before the next General Election is called and purdah prevents any further progress being made.

Hank: I do think that Alex Chalk is listening and we’re getting messages that he’s thinking about what else to do. Then there’s this interaction with the United Nations. And we also know that there are news stories in the pipeline in the next few weeks. The weight of pressure for change on the system is as strong as it’s ever been. The campaigners who’ve done things have done amazing work. MPs are now better informed than perhaps they have been for some time. It is a window of opportunity. It may be that there’s judicial processes that haven’t been thought of because if the United Nations have stated that this is a particular problem, then perhaps there is a legal route that hasn’t been considered before because the United Nations hadn’t made a statement. But now that they have, now that the light is shining on the topic in a way that it hasn’t for a while, I think perhaps, you know, judicial processes might come to bear that haven’t been used before.

Sam: There is also the Victims and Prisoners bill. I’m not sure what happens if a general election comes along, but I think that’s what Sir Bob Neill is counting on if behind the scenes they’re not able to persuade Alex Chalk about re-sentencing.

Hank: It is a good idea. And there’s another amendment proposing an IPP advocacy role for supporting individuals at the parole board and in other ways. But both of those things are slow in coming into force. If there was legislation, it will still take a year. When you’re talking about a few years for anything to come of that, it isn’t very hopeful, is it? We want things to happen now. I think executive action is more likely to solve the problem in the shorter term. But yeah, I fully support everyone doing everything they can in the legislative process.

Thank you for reading to the end of the interview. The topic has engaged you and, hopefully, informed you. But what now – what will you do with what you now know?

There are several things you can do:

1). Write to your MP

Everyone can write to their MP about what you think about IPP sentencing. If you don’t know who your MP is, you can search via the ‘Find You MP’ via this link [ https://members.parliament.uk/members/commons ]. Simply put in your postcode and the page will give you their name and contact details.

2). Social media

If you use a social media platform you can share your thoughts about the IPP sentence. If you want some ideas, you can share a link to the ‘Trapped’ podcast series, or share a link to this blog interview. Or both.

3). Support a campaigning group

You can find a group which campaigns for change in the IPP sentence. There are several. Why not start with the one called UNGRIPP. Their website is www.ungripp.com They are on Facebook and on X, formerly Twitter.

4). Above all, please don’t do nothing.

The watering down of prison scrutiny bodies

I want to concentrate on two scrutiny bodies: His Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons (HMIP) and the Independent Monitoring Boards (IMB).

It appears that both have changed their remit to compensate for the ineffectiveness of their scrutiny. Are they trying to improve something, or are they trying to hide something?

Does the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) want these bodies to obfuscate the facts of the state of prisons? The dilution of scrutiny results in degradation of conditions for your loved ones in prison, staff and inmates alike, both in the same boat.

His Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons (HMIP)

Website https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons/

HMIP inspections have routinely issued recommendations to prisons where failure in certain areas needed to be addressed and in cases where it is possible for issues to be rectified or improved. Applying the healthy prison test, prisons are rated on the outcomes for the four categories below:

- Safety

- Care

- Purposeful activity

- Resettlement

Since 2017, if the state of a prison is of particular concern an Urgent Notification (UN) has been issued. This gives the Secretary of State 28 calendar days to publicly respond to the Urgent Notification and to the concerns raised in it. There have been twelve Urgent Notifications issued so far, and the details from the latest urgent notification for HMYOI Cookham Wood, for example, is uncomfortable reading:

“Complete breakdown of behaviour management”

“Solitary confinement of children had become normalised”

“The leadership team lacked cohesion and had failed to drive up standards”

“Evidence of the acceptance of low standards was widespread”

“Education, skills and work provision had declined and was inadequate in all areas”

“450 staff were currently employed at Cookham Wood. The fact that such rich resources were delivering this unacceptable service for 77 children indicated that much of it was currently wasted, underused or in need of reorganisation to improve outcomes at the site.”

Source: https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2023/04/HMYOI-Cookham-Wood-Urgent-Notification-1.pdf

However, the Inspectorate now have a new system where recommendations have been replaced by 15 key concerns, of these 15, there will be a maximum of 6 priorities. On their website it states:

“We are advised that “change aims to encourage leaders to act on inspection reports in a way which generates real improvements in outcomes for those detained…”

Source: https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons/about-our-inspections/reporting-inspection-findings/

One of my concerns is whether this change will act as a pretext to unresolved issues being formally swept under the carpet. A further concern is what was seen as a problem previously will now be accepted as the norm. As a consequence how will the public be able to get a true and full picture of the state of the prisons?

Will there be a reduction in Urgent Notifications?

I think not.

Or will the issuing of urgent notifications be the only way to get the Secretary of State for Justice to listen and act? In my view, issues that would previously have been flagged up during an inspection are more likely to disappear into the abyss along with all past recommendations which have been left and ignored.

Could it be said that this change of reporting is a watering down of inspection scrutiny that you expect of the Inspectorate?

Before you answer that, let’s look at the IMB.

Independent Monitoring Board (IMB)

Website: https://imb.org.uk/

Until very recently, the Independent Monitoring Board (IMB) website stated that for members: “Their role is to monitor the day-to-day life in their local prison or removal centre and ensure that proper standards of care and decency are maintained.”

But looking at the IMB website today I have noticed that they have changed their role. Instead, it now states that members: “They report on whether the individuals held there are being treated fairly and humanely and whether prisoners are being given the support they need to turn their lives around.”

Contrast that with what the Government website http://www.gov.uk displays, where you will find two more alternatives to what the IMB do:

- 1st. “Independent Monitoring Boards (IMBs) monitor the treatment received by those detained in custody to confirm it is fair, just and humane, by observing the compliance with relevant rules and standards of decency.”

Source: https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/independent-monitoring-boards-of-prisons-immigration-removal-centres-and-short-term-holding-rooms

The first is a large remit for volunteers as there are rather a lot of rules to be aware of. I’m sure the IMB training is unable to cover them all, so how can members be required to know if the prison is compliant or not.

- 2nd. “Independent Monitoring Boards check the day-to-day standards of prisons – each prison has one associated with it. You don’t need specific qualifications and you get trained.”

Source: https://www.gov.uk/volunteer-to-check-standards-in-prison

This checking comes across as a mere tick box exercise, which it certainly should not be. Again, I question whether IMB members training is sufficient. What they say and what actually happens is another example of the absence of ‘joined-up’ government.

In point of fact, the IMB has never been able to ensure anything; if it had then they have completely failed in their remit, as evidenced by the decline in the state of prisons in England and Wales. Clarifying their role is an important change, and one I have been calling out the IMB on for years.

Could it be said that this change of wording is a watering down of monitoring scrutiny you can expect of IMB members?

To help you answer that, you may also need to consider the following:

Although the IMB has become a little more visible, I still have to question their sincerity whether they are the eyes and ears in the prisons of society, of the Justice Secretary, or of anyone else?

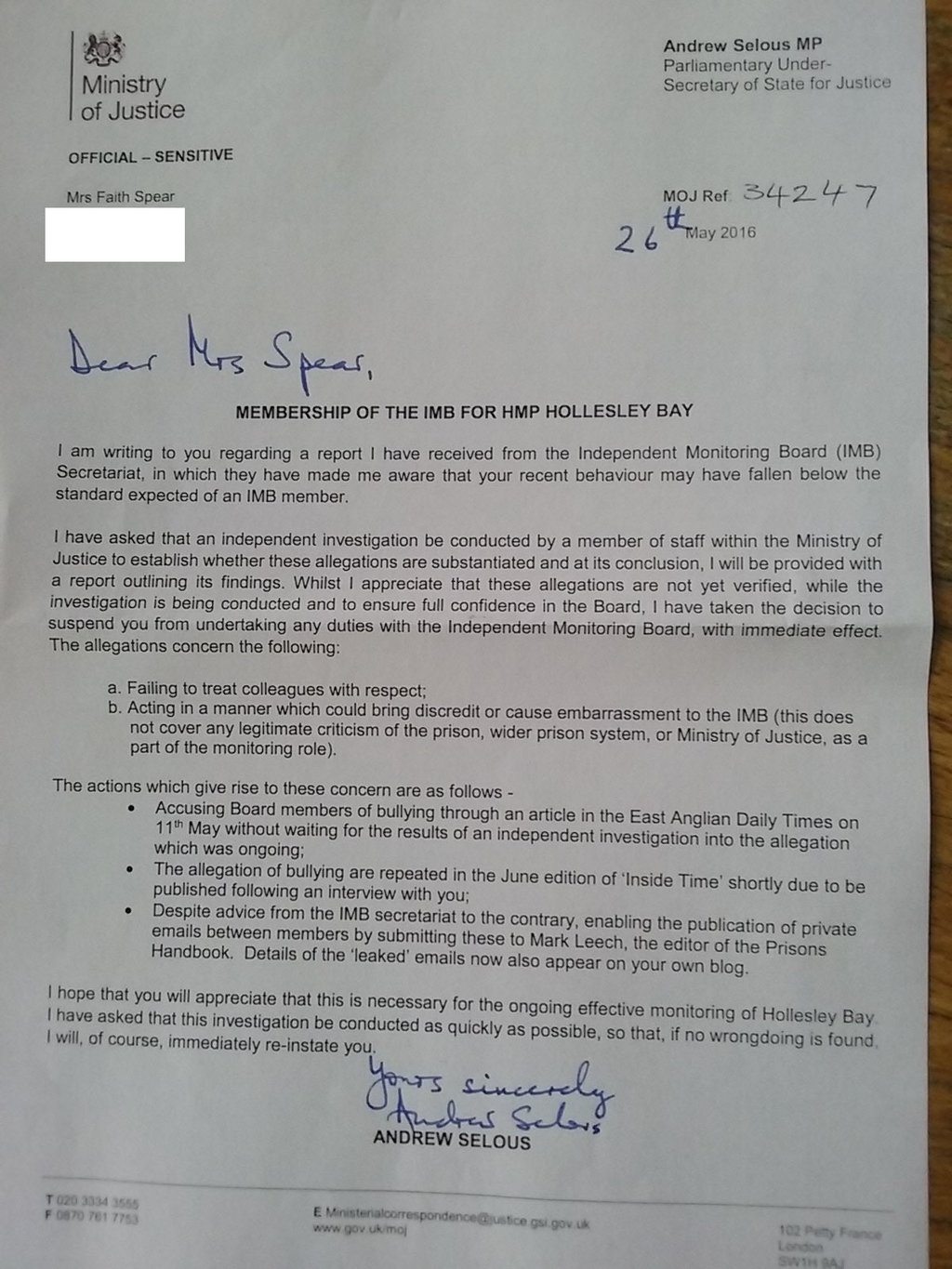

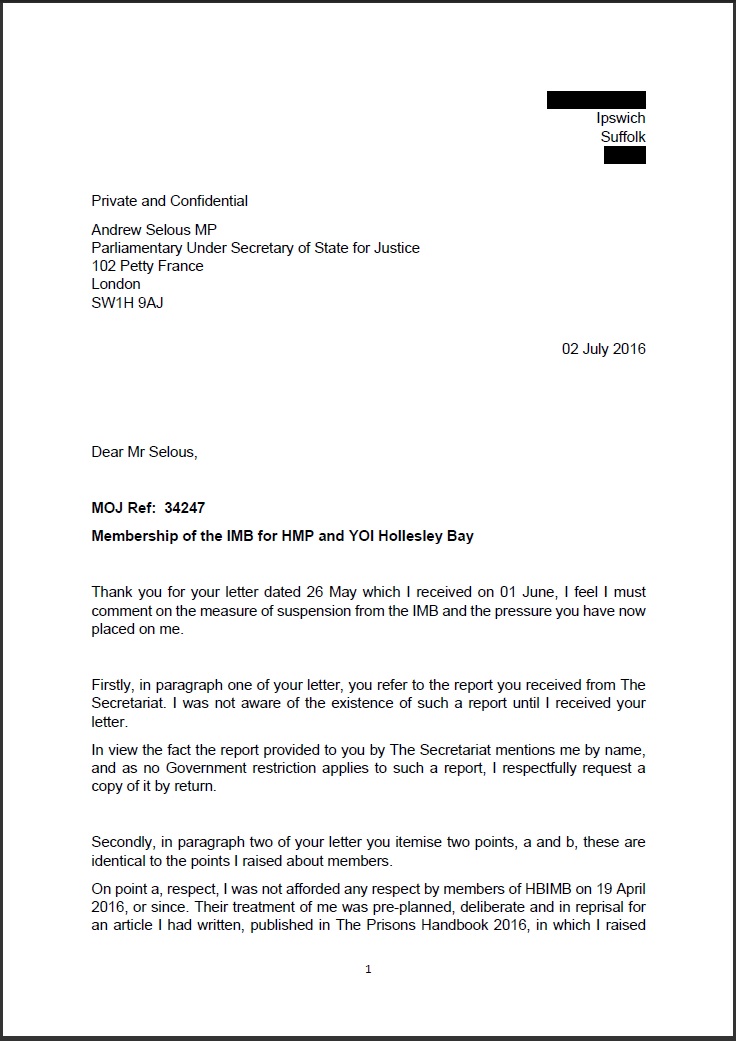

The new strapline adopted by IMB says: “Our eyes on the inside, a voice on the outside.” Admirable ambition, and yet compare that with the lived reality, for example, of my being the eyes on the inside and a voice on the outside, which was exactly the reason why, in 2016, I was targeted in a revolt by the IMB I chaired, suspended by the then Prisons Minister Andrew Selous MP. For being the eyes on the inside and a voice on the outside I was subjected to two investigations by Ministry of Justice civil servants (at the taxpayer’s expense), called to a disciplinary hearing at MoJ headquarters 102 Petty France, then dismissed and banned from the IMB for five years from January 2017 by the then Prisons Minister, Sam Gyimah MP.

If the prisons inspectorate have one sure-fire way of attracting the attention of the Secretary of State for Justice in the form of an Urgent Notification, then why doesn’t the IMB have one too? Surely the IMB ought to be more aware of issues whilst monitoring as they are present each month, and in some cases each week, in prisons. Their board members work on a rota basis. Or should at least.

And then of course there is still the persistent conundrum that these two scrutiny bodies are operationally and functionally dependent on – not independent of – the Ministry of Justice, which makes me question how they comply with this country’s obligation to United Nations, to the UK National Preventative Mechanism (NPM) and Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and other Cruel Inhuman of Degrading Treatment or Punishment (OPCAT), which require members to be operationally and functionally independent.

In 2020, I wrote: “When you look long enough at failure rate of recommendations, you realise that the consequences of inaction have been dire. And will continue to worsen whilst we have nothing more compelling at our disposal than writing recommendations or making recommendations.”

and: “Recommendations have their place but there needs to be something else, something with teeth, something with gravitas way beyond a mere recommendation.”

As a prisons commentator I will watch and wait to see if the apparent watering down of both of these organisations will have a positive or detrimental effect on those who work in our prison environments and on those who are incarcerated by the prison system.

As Elisabeth Davies, the new National Chair of the Independent Monitoring Boards, takes up her role from 1st July 2023 for an initial term of three years, I hope that the IMB will find ways to no longer be described as “the old folk that are part of the MoJ” and stand up to fulfil the claim made in their new strapline: “Our eyes on the inside, a voice on the outside”.

And drop the misleading title “Independent.”

~

Photo: Pexels / Jill Burrow. Creative Commons

~

Please leave a message after the tone…

I have been waiting eagerly for more news as to how the Independent Monitoring Board (IMB) would operate ‘indirect monitoring’ of prisons and places of detention as it had stated on its website on 30th March 2020: “This is a fast-moving situation…” but there has been nothing for 4 weeks.

When a new hotline initiative was first mentioned by the National Chair in an update on the IMB website it claimed:

“We are in discussion at a national level with specialist contractors about the possibility of freephone lines to enable applications using in-cell telephony and the additional telephone capacity proposed by the Prison Service”

Seeing the headline on their website this morning, “Independent monitors launch new hotline for prisoners to report concerns during pandemic”, I was relieved. That is until I read the detail.

A few things about it stood out to me.

First, this hotline will only be available to 13 prisons, around 11% of the entire estate.

The prisons taking part are Wayland, Pentonville, Lewes, High Down, Berwyn, Woodhill, Eastwood Park, Bronzefield, Durham, Buckley Hall, Swinfen Hall, Onley and Elmley.

The hotline will be part of a new pilot scheme running for 6 weeks.

Ten thousand prisoners will be able to call for free from a phone in their cell or a communal phone.

That’s a start, but what about accessibility to the IMB in the meantime for the other seventy one and a half thousand people in prison?

Lines will be open, with a voicemail service, from 7am-7pm seven days a week.

In other words prisoners will not actually be able to talk to someone; it’s an answerphone and their message will be recorded.

Second, the actual process.

The prisoner’s concerns will be passed on to the relevant board, who will respond through the ‘email a prisoner’ service, or through the normal IMB routes or the IMB clerk.

It doesn’t say who will pass on the prisoner’s concerns and to the relevant Board. Presumably a member of staff will have to listen to the message and then write out the complaint/concern and send it to the relevant Board via email. Replies from IMB to the prisoner will then go through the ‘Email a Prisoner’ service.

Incidentally, the ‘Email a Prisoner’ website states:

“We are sending your messages to the establishments daily, as normal, but please note that prison staff are very compromised at the moment, so there may be instances where messages and replies are unfortunately delayed”

I cannot see how using an already saturated system will be particularly efficient.

Moreover, giving staff an additional task of transcribing the messages and sending them to the IMB would not be seen as a priority.

Even using the IMB clerk, which I’m aware happens in some prisons, is not the best way as they are HMPPS staff. In fact I know of one IMB Board where the clerk was closely related to one of the Governors at the same prison.

Like calls to the Samaritans, these calls will be confidential, and not recorded by HMPPS

Third, how can these recorded calls ever be considered confidential?

A prisoner telephones the hotline and has to leave a message on an answering service as the hotline is unmanned. The prisoner will have to leave personally identifiable information: their full name, their prisoner number and the name of the prison they are in. No mention is made in the announcement as to where these recorded calls are stored or for how long, nor who has access to them.

Someone has to relay these to the relevant IMB Board which means either sending a copy of the digital recording or transcribing them. Either way the confidentiality which should exist between a prisoner and a Board member is broken and trust is compromised.

Once the message is in the hands of the relevant IMB Board, assuming it reaches the correct one first time and does not go astray, the IMB must then find the information and respond to the prisoner.

The reply from the IMB to the prisoner must be made via the ‘Email a Prisoner’ service, which as everyone knows is a web based email service that depends on a member of the prison staff logging in and printing off to hardcopy all the individual messages sent to prisoners.

This step breaks for a second time the confidentiality that should exist between a prisoner and the IMB Board. Please don’t tell me that messages arriving for prisoners are not read by staff.

One more point worth making here is that only 9 out of the 13 prisons in the pilot have in place the ability for prisoners to reply back to messages from the IMB using the ‘Email a Prisoner’ platform. In other words, there will be 4 prisons where prisoners will have to start the process all over again should the response from the IMB not answer their concerns.

(Immigration detainees can already email IMBs directly which surely must be a much easier solution, and far more likely to be confidential as well as quicker)

Whereas it is only a pilot and teething troubles will naturally be ironed out, this system is fundamentally flawed from the beginning.

For it to have any credibility in effective monitoring the prisons in England and Wales the IMB must urgently rethink what it considers to be acceptable ‘indirect monitoring’.

Update: A short message I received from Sarah Clifford, IMB Head of Policy and Communications:

Hello Faith – Just wanted to clarify that the IMB freephone pilot is a live service, staffed eight hours a day by IMB members with voicemails as a back up. I have added a note to the IMB website announcement to that effect: https://www.imb.org.uk/independent-monitors-launch-new-hotline-for-prisoners-to-report-concerns-during-pandemic/. Many thanks.

This is incredible that this clarification was needed. This should have been on the website from the start without myself having to point it out in a blog. There was an uproar when I copied the IMB plans straight from their website. There was no hint at all that it would be a live service, staffed eight hours per day by IMB members. This was an essential point that was ommited.

Lets hope the IMB itself becomes a little more transparent and accountable.

~

Just how ‘independent’ is the Independent Monitoring Board?

For many years I have struggled with the concept of the Independent Monitoring Board (IMB) being actually independent.

This is an organisation which was based at the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) HQ, Petty France for many years, but now shares open plan offices in a Government Hub at Canary Wharf alongside HM Inspectorate of Prisons, Prison and Probation Ombudsman (PPO), Parole Board for England and Wales and the Lay Observers Secretariat.

The introduction of IMB’s new Governance structure, where the role of President was replaced by a Chair and an additional layer of management, has failed to persuade me otherwise.

Dame Anne Owers, formerly Chair of The Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC) and prior to that Chief Inspector of Prisons (2001-2010), took up the role of National Chair of the IMB in November 2017.

We appear to differ on the definition of independence. Or do we? Across a committee room in the House of Lords, she and I exchanged glances as soon as the word “independence” was mentioned. I get the impression she knows it’s not.

Does it matter that the IMB is not independent?

It unquestionably matters because an application to the IMB requires a response within a certain time frame from an “independent” voice. But as the IMB is a department of the Ministry of Justice any problems or issues highlighted cannot be dealt with in a proper manner if they are basically monitoring themselves. The phrase “marking their own homework” comes to mind.

Is this the reason why the IMB does not have any real powers?

The IMB was established by statute (Offender Management Act 2007, Section 26), unlike the National Chair or the Management Board, neither of which are statutory entities. IMB responsibilities within prisons are set out in Section 6 of the Prison Act 1952 (as amended), Prison Rules Part V 1999, and Young Offenders Institution Rules Part V 2000.

In addition, IMB responsibilities in the Immigration Detention Estate (IDE) are set out in Section 152 of the Immigration and Asylum Act 1999, the Detention Centre Rules Part IV 2001 and the Short-term Holding Facilities Rules Part 7 2018.

In Summer 2019, MoJ and IMB co-produced a 23-page document “Protocol between The Ministry of Justice as the department and the Management Board of the Independent Monitoring Boards” A copy is available via this page of the IMB website.

This is where it gets interesting.

This protocol was drawn up by the MoJ and the Management Board of the IMB, setting out the role of each body in relation to the other. Furthermore, it sets out the responsibilities of the principal individuals running, sponsoring and overseeing the IMB Secretariat.

At this point, it’s relevant to look at the IMB structure:

-

First, we have the National Chair: Dame Anne Owers, appointed by the Secretary of State for Justice (Ministerial appointment) and a non-statutory public appointment

-

Second, there is the IMB Management Board, appointed by the National Chair which sets out the overall strategy and corporate business plans for the IMB (Protocol, p. 2: 1.3)

Both work with and through a regional representative’s network also appointed by the National Chair, providing support and guidance to the IMB.

-

Third, we come to the IMB Secretariat, a team of MoJ civil servants providing the IMB with administrative and policy support. This team is tasked by the National Chair and Management Board

It is the National Chair, Management Board and regional representatives that have the responsibility for the operation of this protocol. Yet with all the effort in its production this protocol does not confer any legal powers or responsibilities (Protocol, p.2: 1.6).

This protocol is approved by the Permanent Secretary of the MoJ, who is Sir Richard Heaton, and the sponsoring Minister. It is signed and dated by the Permanent Secretary (i.e. Sir Richard Heaton) and the National Chair (i.e. Dame Anne Owers).

But why should the independence of the IMB, the National Chair and the Management Board be of paramount importance? (Protocol, p.4: 3.1)

Let me try to answer this succinctly.

The IMB is part of the UK’s National Preventive Mechanism (NPM), designated by the Government to meet the obligations of the United Nations Optional Protocol to the Convention Against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (OPCAT).

To be part of the OPCAT, it is necessary to be independent (Part I, Art 1; Part II, Art 5.6; Part IV, Art 17; Part VII, Art 35).

NPMs are required to be functionally and operationally independent. Therefore, the IMB is required to be functionally and operationally independent.

Yet:

-

IMBs are sponsored by MoJ

-

National Chair is a ministerial appointment

-

IMBs receive funding through the MoJ and the Home Office

-

MoJ is responsible for ensuring the use of funds meets the standards of governance, decision-making and financial management, as set out in Managing Public Money 2013 revised 2018

-

The head of the IMB Secretariat accounts to the Principal Accounting Officer (PAO) for the appropriate use of resources

-

The PAO is the Permanent Secretary of the MoJ (Sir Richard Heaton) and is responsible for ensuring that IMB meets the standards set out in Managing Public Money

-

MoJ has appointed a sponsorship team

-

The sponsorship team is drawn from the Sponsorship of Independent Bodies Team in the MoJ’s Policy, Communications and Analysis Group. Its policy responsibilities are to act as the policy interface for the IMBs and assurance responsibilities are to act as a “critical friend” to the IMBs

-

The Head of the IMB Secretariat is a civil servant and employee of the MoJ and has accountability for IMB finances

In conclusion

It appears throughout this document that the MoJ exerts operational and functional control of the IMB. If that is the case then it is not independent, cannot call itself “Independent” and questions should now be asked concerning its membership of NPM and OPCAT.

IMB is not some vanity project for Ministers to appoint people to and to dismiss people from. Neither is it an arms-length body of any central Government department to sponsor in a whimsical way for its own ends.

Related Links

Protocols:

MoJ and HM Inspectorate Probation Download PDF

20 pages

Dated: 17 Apr 2018

Signed: Heaton 17 Apr 2018 and Stacey 02 May 2018

Published: 17 May 2018

MoJ and PPO Download PDF

19 pages

Dated: 01 Mar 2019

Signed: Heaton 20 Feb 2019 and McAllister 27 Feb 2019

Published: 12 Mar 2019

MoJ and IMB Download PDF

23 pages

Dated: 25 Jul 2019

Signed: Heaton 11 Jul 2019 and Owers 25 Jul 2019

Published: 14 Aug 2019

MoJ and HM Inspectorate Prisons Download PDF

24 pages

Dated: 10 Oct 2019

Signed: Heaton 30 Sep 2019 and Clarke 14 Oct 2019

Published:

Can you see the common denominator between all these protocols?

NB. The Protocol between MoJ and HMI Prisons was promised by the Ministry to the Commons Justice Select Committee back in March 2016.

~

This article was first published in Converse, November 2019 print edition and The Prison Oracle on 14 October 2019.

~

The paralysis of too many priorities.

Sat immediately behind the new Secretary of State at the Justice Select Committee (@CommonsJustice) on 07 September, I registered a lot of awkwardness that was beyond mere nervousness felt by many a new joiner.

Thatcher Room, 07 Sept 2016

Just like Gove’s debut in front of the same Committee where he rattled on about “we’re reviewing it” (yes, I was there for that one too), Liz Truss (@trussliz) talked largely about the formulating of “plans” but on the day said nothing about tangible actions she will take.

How many more reviews do we need?

Has Truss inherited a poisoned chalice passed from one SoS to the next? Her department has a huge accumulated mess to sort out and doesn’t know what to do about it. Is she wondering what to tackle first? The paralysis of too many priorities?

Her critics say she’s doing things wrong. Look at it for yourself and you’ll see some of the priorities she is confronted with:

- Extremism and radicalisation in prison

- Violence against other offenders and against prison staff

- Over population

- Under staffing of prisons

- Death in custody

- Drugs and drones

- Education and purposeful activity

- Resettlement and homelessness on release

You would think her advisors would know what the order of priorities are. They don’t, or if they do, they obviously prefer the relative safety of “talking shop” over the tough task of taking concrete action on these priorities.

The key question people are asking is has she actually got the shoulders for the job; she has the high office and gilded robe of the Lord Chancellor but does she have the support of those working within the criminal justice system?

Soon after her appointment from Defra to Ministry of Justice, Liz Truss paid token visits to two prisons but cannot be expected to become an instant expert on the prison system.

What other mess does the SoS need to deal with?

The system of prison monitoring is in a mess. The IMB Secretariat is in utter disarray. They say they have policies and procedures but don’t always follow them themselves. For the most part, IMBs are doing their own thing. There’s no real accountability anymore. It’s a disgrace and it’s deplorable that it’s been allowed to get as bad as it has.

Faith Spear

For my critique of prison reform and Independent Monitor Boards, I’ve been put through two MOJ investigations. Each one takes away a little piece of me. But for me it’s always been about the issues. That’s why they can’t and won’t shut me up.

The message of prison reform has become urgent and has to get to the top. If no one else will step up and if it falls to me to take it then so be it.

No accountability anymore? Give me an example.

You want an example? Here’s one of many: At HMP Garth, the IMB Chair issued a Notice To Prisoners 048/2016 dated May 2016 without the authority to do so, and apparently without the Board agreeing it. The Chair acted unilaterally outside of governance. I found out about it because a copy of that prison notice was sent to me as it happened to be about the article “Whistle Blower Without a Whistle” that I’d written for The Prison Handbook 2016 that the IMB Garth Chair was pin-pointing, (accusing me of a “rant” whilst both his prison notice and covering letter were dripping with distain).

I’m still standing by all I said in my Whistleblower article even though writing it has been at a high personal cost. In all candour, any pride I may have had in writing it has been completely sucked away from me. It’s back to the bare metal. The inconvenient truth of what I wrote remains. Readers will find that my main themes also feature prominently in the findings of the report by Karen Page Associates, commissioned by the MOJ at a cost to the taxpayer of £18,500.

An invite I received from Brian Guthrie to the forthcoming AGM of Association of Members of IMB says it all. It read:

“From the Chair Christopher Padfield

AMIMB – the immediate future

IMB needs a voice. We believe that without AMIMB this voice will not be heard. AMIMB intends to raise its voice, but needs the support of our members.

An outline plan for the immediate future of AMIMB will be put up for discussion at the forthcoming AGM (11 October 2016 at 2 Temple Place). It aims to respond both to the main needs and opportunities, and to the practicalities of the current situation.The greatest need, as the executive committee of the AMIMB sees it, is to achieve a public voice for Independent Monitoring Boards – to let the British public know what we, as monitors, think about prison and immigration detention policy and practice in England and Wales and the impact this has on the men, women and children detained; to achieve some public recognition for the role of IMBs; in short to speak out about what we hear and see. We have urged the National Council to do this itself, but to no avail. In character, the NC propose as their contribution to the Parliamentary Justice Select Committee’s current consultation on Prison Reform, a response to a procedural question: ‘are existing mechanisms for … independent scrutiny of prisons fit for purpose?’ If the NC cannot or will not speak out, AMIMB should.”

Mr Padfield has served as IMB Chairman at HMP Bedford but to my knowledge has never been suspended pending investigation by the Prisons Minister like I was for speaking out on such things.

And therein lays the dilemma: whereas the official line is to encourage monitors to speak out, the reprisals levelled at you when you actually do are still shocking.

Is this what happens to women who use their voice?

People want you to get back in the box.

To shut up.

To go away.

The IMB doesn’t need a makeover; that would only hide most of the systemic problems behind filler and veneer. So rebranding clearly isn’t going to be the answer any more than putting lipstick on a pig.

People who think I want to abolish the IMB have totally misjudged me and the situation. I don’t want to abolish it. Far from it. I want the IMB to perform like it was set up to under OPCAT and to be all it should be as part of our NPM.

The clue is in the name: Independent. Monitoring. Board.

Have you noticed that the MOJ is haemorrhaging people at the moment?

Maybe Liz Truss could use that as an opportunity to enlist the help of those who do give a damn about the conditions in which people are held in custody and who do have a clue about strategies to stem radicalisation in prison, minimise violence, reduce prison over population, have the right staff and staffing levels, reduce death in custody, counter drones and drug misuse, revitalise education and purposeful activity, and last but not least, resettle and house people after their time in custody.

Join the conversation on Twitter @fmspear @trussliz @CommonsJustice #prisons #reform #IMB #AMIMB #SpeakUp

First published 17 Sept 2016.

Edited 18 Sept 2016.

~