Home » crime reduction

Category Archives: crime reduction

Chocolate & Grace: Succeed in the face of adversity

Back in 2017, in The Clink restaurant in HMP Brixton, I had lunch with Chris Moore, the then Chief Executive of The Clink Charity, and a lady from Scotland. We listened carefully as she shared her vision of helping women caught up in the justice system, with chocolate. Her vision was realised later that year, but we lost touch.

Last week, eight years later at Lady Val Corbett’s Professional Women’s networking lunch, I met Louise Humpington, CEO of Positive Changes, a CIC trading as Chocolate and Grace. The very same initiative that I had heard about all those years earlier. Louise became involved in July 2024.

This is the story of Chocolate & Grace, kindly written by Louise:

In a bustling kitchen in Stirling where the aroma of melting cocoa lingers, something more profound than chocolate is being crafted. Chocolate & Grace is not simply about indulgence; it is about empowerment, dignity, and rewriting futures.

At its heart, this initiative provides women who have lived experience of the justice system, with a safe, supportive space to heal, connect, and grow. Women describe the empowerment they feel when they are truly valued, treated with respect, and given the agency to rebuild their lives. Here, they are not defined by past mistakes but celebrated for their resilience, strength, and capacity for transformation.

Isolation is one of the silent challenges faced by many women leaving the justice system. Chocolate & Grace breaks that cycle by fostering community, reducing loneliness, and encouraging meaningful relationships. In doing so, it helps rebuild lives and, crucially, reduces reoffending—creating a positive ripple effect across society. The impact is not only personal but economic: lives rebuilt mean less strain on the public purse and a healthier, more connected community.

Every chocolate made is infused with purpose. Behind each truffle or bar is a story of hope, courage, and determination. Alongside training and employment opportunities, the program offers trauma-informed support and a platform for women’s voices to be heard, acknowledged, and amplified. The women are credited not as passive recipients of help, but as active changemakers who demonstrate extraordinary commitment to transformation.

Chocolate & Grace is proof that with compassion, respect, and opportunity, cycles can be broken. It is a movement that blends social impact with sweet creativity—reminding us that true empowerment is not given but cultivated, one act of grace, one piece of chocolate, one woman at a time.

But this approach isn’t just important for the women being supported by Chocolate & Grace, it also represents a critical redefining of what leadership and success look like.

This change matters not only because it corrects decades of narrow norms, but because it unlocks better outcomes for organisations, teams, and society. One in four people in the UK will have had been subjected to Adverse Childhood Experiences or some other trauma. Better recognising how marginalised groups and disenfranchised people can contribute because of their lived experience and not in spite of it, is not, therefore a nice to have, it’s a fundamental shift that society needs.

When we value difference, leadership becomes more human. It shows the value of connection, trust, and authenticity as strengths, not liabilities.

It shifts the metrics by creating a space where success isn’t defined solely by outcomes like profit, efficiency or hierarchy. Wellbeing, purpose, sustainability, inclusion are finding a space and making leadership more holistic and resilient in turbulent times.

When the rules are reworked, it opens up space for diverse voices that have been traditionally marginalised or excluded. It empowers people, amplifies their voices and revers the value of their perspective.

There is no question that challenges remain, but as we continue to push boundaries and challenges status quo, momentum builds. Systemic obstacles (bias, unequal expectations, lack of access) still create barriers. But as more women lead by new norms, those norms themselves become harder to ignore or dismiss. We are changing the normative landscape in leading by example, and in amplifying the voices of those who have the most to teach us about what it is really like to succeed in the face of adversity.

The chocolates are delicious, if you would like to support this inspiring organisation have a look at their shop and treat yourself (and others) https://www.chocolateandgrace.co.uk/collections

Keir Starmer whips AGAINST Lord Thomas amendment to end shocking #IPP scandal as campaigners vow to fight on

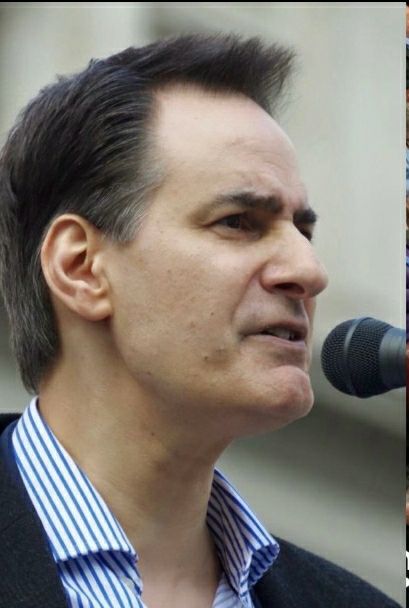

Campaigning Lawyer and CEO of CAMPAIGN FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE Peter Stefanovic – who’s films have been watched hundreds of millions of times online – has posted a new film calling on Prime Minister Keir Starmer to end the IPP scandal once and for all by adopting a plan drawn up by Lord Thomas, the former Lord Chief Justice.

BACKGROUND

IPP sentences were introduced in England and Wales by the then New Labour government with the Criminal Justice Act 2003. It sought to prove it was tough on law and order by putting in place IPP sentences to detain indefinitely serious offenders who were perceived to be a risk to the public. However, they were also used against offenders who had committed low-level crimes, resulting in people spending 18 years in jail for trying to steal a coat or imprisoned for 11 years for stealing a mobile phone. In one instance 16 years in jail for stealing a flowerpot.

UNLAWFUL

In 2012, after widespread condemnation and a ruling by the European court of human rights that such sentences were, “arbitrary and therefore unlawful”, IPP terms were abolished by the Conservative government. But the measure was not retrospective, and thousands remain in prison.

Over 90 people serving sentences under the discredited IPP regime have sadly taken their own lives whilst in prison. In 2023 we saw the second year in a row of the highest number of self-inflicted deaths since the IPP sentence was introduced.

Former supreme court justice Lord Brown called IPP sentences: “the greatest single stain on the justice system”. When Michael Gove was justice secretary, he recommended, “executive clemency” for IPP prisoners who had served terms much longer than their tariffs. But he didn’t act on it. Lord Blunkett, the Labour Home Secretary who introduced the sentences, regrets them, stating: “I got it wrong.” And more recently, Dr Alice Edwards, the UN rapporteur for torture has called IPP sentences an “egregious miscarriage of justice.” Even former Justice Secretary Alex Chalk KC has called them a stain on the justice system, yet despite that, the previous Conservative Government refused to implement the Justice Committees recommendation to re-sentence all prisoners subject to IPP sentences.

CAMPAIGN FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE

Their families and campaign groups have been fighting to end this tragic miscarriage of justice for more than a decade and films posted online by social media sensation and campaigner Peter Stefanovic have ignited a wider public storm on this tragic miscarriage of justice gathering millions of views.

You can watch Stefanovic’s latest film here:

https://x.com/peterstefanovi2/status/1937394593672089988?s=46&t=g6PUk4YExrOYprJSzQZ3lw

It is not surprising that the public reaction to his films have been one of shock, outrage, and disbelief.

PUBLIC SUPPORT

Stefanovic has said: “The public support for my films has been overwhelming and the comments they are getting are a testament to the public’s anger, outrage and disbelief at this tragic miscarriage of justice.”

HOPE FOR JUSTICE

Now – the Labour government is being given the chance to end this monstrous injustice once and for all by adopting a plan drawn up Lord Thomas, the former Lord Chief Justice.

An expert working group convened by The Howard League and led by Lord Thomas has come forward with considered proposals aimed at protecting the public while ending the long-running IPP scandal.

Below are the members of the working group:

Farrhat Arshad KC, barrister

Dr Jackie Craissati, clinical and forensic psychologist

Andrea Coomber KC (Hon), Chief Executive of the Howard League for Penal Reform

Dr Laura Janes KC (Hon), solicitor

Dr Frances Maclennan, clinical psychologist

Andrew Morris, served IPP sentence

Dr Callum Ross, forensic psychiatrist

Claire Salama, solicitor Sir John Saunders, retired High Court judge and former Vice Chair and member of the Parole Board

Professor Pamela Taylor, psychiatrist and academic

Paul Walker, Therapeutic Environments Lead for the OPD Pathway (HMPPS)

The working group’s report puts forward six recommendations – the most important of which is a change to the Parole Board test which would require the Parole Board to give people on IPP sentences a certain release date, within a two-year window, and to set out what action is required to achieve that safely.

Setting a date of up to two years provides a long period of time to enable professionals and statutory agencies to work together and help the person to prepare for a safe release – it completely knocks on the head any argument the justice secretary has previously raised about public safety and will end once and for all one of the most cruel and monumental injustices of the past half century.

Campaigners have hit out at the “short-sighted” decision not to include prisoners on indefinite sentences in the plans announced by the government to reduce the prison population.

The government has recently published its long-awaited sentencing review, led by former Conservative justice secretary David Gauke, who recommended that some offenders who behave well in jail only serve a third of their term in custody before being released. Yet the Chair of the Justice Committee, Andy Slaughter MP has raised the point recently that “Even if David Gauke’s recommendations are wholly successful the prisons will still be full, and this has unintended consequences.”

With Government Ministers saying they have inherited a prison system “on verge of collapse” Stefanovic says this is “nonsensical”.

He concludes his latest film saying:

“With our prisons at breaking point now is the time for James Timpson – the prisons minister and Labour peer to accept this sensible, workable and detailed plan and seek to close this shameful chapter in the history of British criminal justice. If the Justice Secretary refuses to sign off on this plan for fear of handing ammunition to ignorant critics who accuse her of being soft on crime the Prime Minister, a former director of public prosecutions, who understands the criminal justice system better than any minister should instruct her to act on the proposals – because the simple fact is that by refusing to do so Keir Starmer’s government would become responsible for allowing one of the most cruel, inhumane and monumental injustices of the past half-century – a scandal rightly described as a stain on our justice system – a scandal described by the UN rapporteur for torture as an egregious miscarriage of justice and psychological torture – and which likely breaches Article 3 of the Human Rights Act – to be continued and perpetrated – and I for one cannot believe that that is what a Labour government would want to happen”

Update:

We have now found out that Keir Starmer has whipped against Lord Thomas to end this shocking IPP scandal.

END THE “MONUMENTAL INJUSTICE” OF IPP SENTENCES

Today we have heard The Secretary of State for Justice, Shabana Mahmood announce a temporary change in the law, to release prisoners after completing 40% of their sentence in prison rather than 50%. But for those on an IPP sentence they once again see others released whilst they continue to languish in prison.

LETTER TO THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR JUSTICE

Social media sensation Peter Stefanovic, a lawyer, campaigner & CEO of CAMPAIGN FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE has joined a coalition of 70 criminal justice experts, civil society organisations, leading activists and campaigners in signing an open letter to Keir Starmer’s new Labour Government and to the Justice Secretary, Shabana Mahmood, calling on them to deliver crucial reforms to Imprisonment for Public Protection (IPP) sentences, a national scandal which has claimed more than 100 lives since 2005.

Peter Stefanovic has produced films which have been viewed hundreds of million of times, his latest video covers some of his concerns expressed in the letter, he said:

“I’ve just signed a letter calling on the new Justice Secretary to work at pace to end one of the most shocking, cruel, inhumane, degrading and monumental injustices of the past half-century – IPP sentences – a scandal which has a already claimed the lives of 90 people serving IPP sentences in prison and a further 31 that we know of in the community”

He continued:

“I cannot overstate the urgency on this – in June one person serving an IPP sentence – a staggering 12 years over tariff set himself alight, another began his second hunger strike. This insanity has got to end – we must now put a stop to this inhumane and indefensible treatment which has absolutely no place in a modern Britain and political leaders – previously lacking the courage to take action – must now find the courage to do so.”

BACKGROUND

IPP sentences were introduced in England and Wales by the New Labour government with the Criminal Justice Act 2003, as it sought to prove it was tough on law and order. They were put in place to detain indefinitely serious offenders who were perceived to be a risk to the public. However, they were also used against offenders who had committed low-level crimes.

Astonishingly, this sentence has led to some people spending 18 years in jail for trying to steal a coat or imprisoned for 11 years for stealing a mobile phone. Another served 16 years in jail on a three-year IPP tariff for stealing a flower pot at the age of 17.

ABOLISHMENT OF THE IPP SENTENCE

In 2012, after widespread condemnation and a ruling by the European court of human rights that such sentences were, “arbitrary and therefore unlawful”, IPP terms were abolished by the Conservative government. But the measure was not retrospective, and thousands remain in prison.

EGREGIOUS MISCARRIAGE OF JUSTICE

Former supreme court justice Lord Brown called IPP sentences: “the greatest single stain on the justice system”. When Michael Gove was justice secretary, he recommended, “executive clemency” for IPP prisoners who had served terms much longer than their tariffs. But he didn’t act on it. Lord Blunkett, the Labour Home Secretary who introduced the sentences, regrets them, stating: “I got it wrong.” And more recently, Dr Alice Edwards, the UN rapporteur for torture has called IPP sentences an “egregious miscarriage of justice.” Even former Justice Secretary Alex Chalk KC has called them a stain on the justice system, despite that, the previous Conservative Government refused to implement the Justice Committees recommendation to re-sentence all prisoners subject to IPP sentences.

HOUSE OF LORDS DEBATE

In a debate in the House of Lords in May, Lord Ponsonby – leading for Labour on justice said:

“In Government we will work at pace to bring forward an effective action plan that will allow the safe release of IPP prisoners where possible”

RESOLVE THIS INJUSTICE

In their letter, the campaigners “urge the new government to honour its commitment, made in opposition, to “work at pace” to resolve this injustice.

Stefanovic says “The new government must now honour the commitment it made in opposition and work at pace to end this cruel, inhumane, degrading and most monumental of injustices”

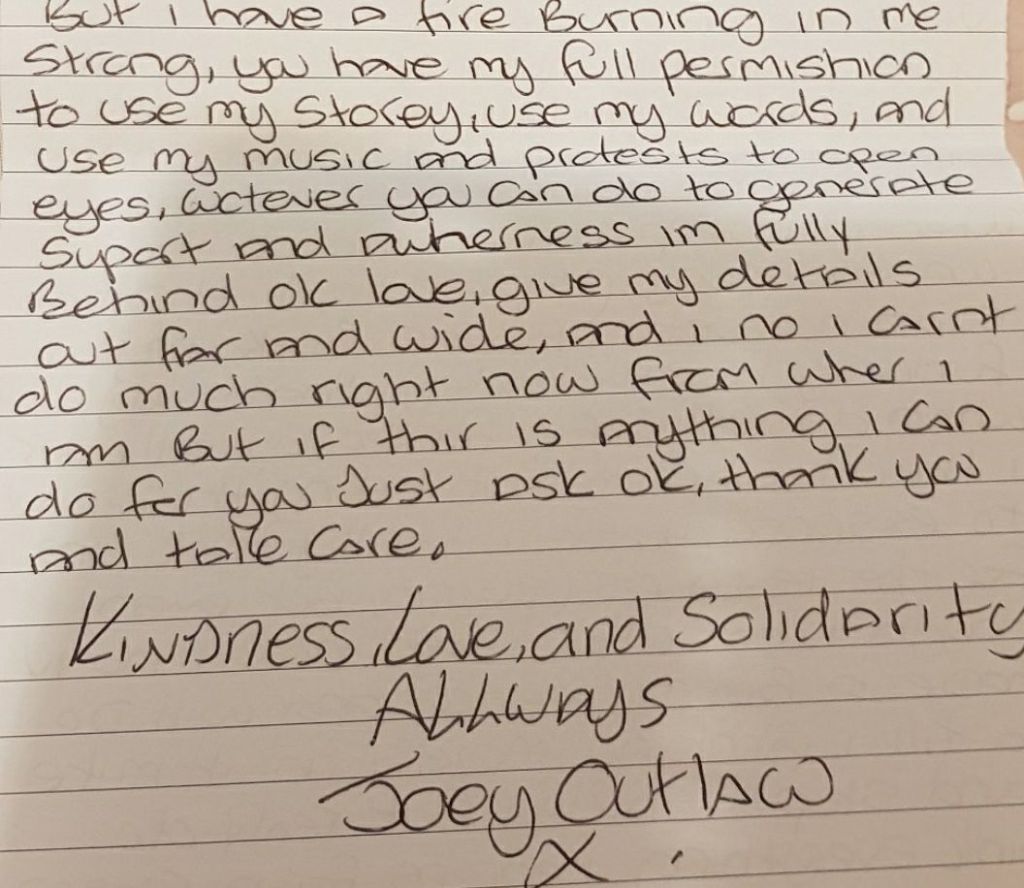

Joe Outlaw, an IPP: In his own words, part 1.

You may remember back in April 2023 a prisoner staged a 12-hour protest on the roof of Strangeways prison about the injustice of IPP prisoners. His name is Joe Outlaw, 37 years old and with 33 previous convictions. I was sent his story…

This is his story, in his own words

My story began in Bradford, Sunny West Yorkshire, and one of two children. The other being my sister Jill. At the start was a typical council estate life in the late 1980s. My Mom tried her best to bring us up as well as she could, but was cursed sadly by manic depression, what they now call bipolar. But this was not a fashion statement back then, it was dangerous and scary to witness. My Father was a gypsy from Hungary who never honoured his responsibilities as a father. Instead choosing to do a David Copperfield and disappear.

My sister was seven years older than me and would soon become my mum to be. By age three social services were involved and after one of my mom’s manic episodes, it was too dangerous for them to risk leaving us there. We were both placed on a full care order, which would cave the path years of painful memories I wish I could erase. Thankfully, they kept and Jill together in a wide range of foster parent, children’s homes and respite carers. Jill tried her best and I’m grateful for all the love she gave despite having to deal with her own sorrow as a young woman.

By the time she was 18 she had to leave me and that’s when I went off the rails. Constantly running away, and naively feeling more secure on the streets.

This stage of teenage growth embedded criminal dynamics to my survival and behaviour.

By fourteen social services basically gave up on me and I tell no lies when I say I was put in a B&B to live by myself, and no homes would take me. I was on a full care order until eighteen. Yet they lacked the support, guidance and interventions to raise me as expected. This happen twice, once in Shipley, West Yorkshire, and once in Wales at fifteen.

My criminality and reckless actions would continue for years.

I will say though, I was never a violent young offender. It was always nicking cars, motorbikes stealing etc. More a thief then a robber. I never sadly did manage to become rooted. I was always galivanting around the country, place to place. From twelve to nineteen life was an adventure, me a tent and a dog. Somehow, I always managed to pick up a stray for somewhere. I’ve always found animals and nature amazing. As a child I would find comfort and solace in beings alone in woods or on beaches. Just me and the pooch pondering life and all its confusions.

Well at age nineteen as destined, I get my first bit of proper jail.

Someone passed me an air rifle at a bus stop in the sticks in north Wales, and as he passed it to me, I generally shot him in the foot by mistake. I just grabbed the gun and the trigger was so sensitive, it popped and went off. I got three and a half years for that. But when I think back, I can barely remember it, it was just a life being in a children’s home, but I couldn’t run away and people were older, strange eh! Well to jump forward some years, by 23 I found love while I was travelling yet again. And for the first time in my life rooted in western-super-mare.

Despite being rooted my lifetime habits of survival were too deeply set.

To survive I sold weed, wheeling and dealing etc. and one night I was late in and my girlfriend at the time was arguing with me saying she was sick of me having my phone going off all the time, coming in late etc. She would take Valium on a night to sleep and said for me to take some and wind down, but I didn’t take any drugs like that back then. I had gone through all drug phases from young, except crack and heroin and by that time all I did was smoke weed. Well after some arguing, I just wanted to shut her up frankly, and I took three little blue tablets off her. Now little did I know that among the criminal knowledge, Valium are called Little Blue charge sheets, referring to their colour being blue, and the fact that people with criminal tendencies either wake up in cells, hence the charge sheet reference or they wake up surrounded by phones, money etc and not to have a clue how it all got there or what they had been up to obtain said items.

Needless to say, this inadvertently would be the little blue charge sheet that changed my life forever.

I do not remember a single thing of what I’m about to tell you and this is only what people have told me and information from statements etc. I took the tablets and drank some Southern Comfort, passed out, woke up and demanded more valium off my girlfriend. Once taken three more I then left the flat and went to a party. Where I stole a shotgun and shells, and then went into my local takeaway, where I went to every day by the way, and held it up at gunpoint. I left after being in this 60 seconds, and now rich with a grand sum of 200 pounds. Which by the way I would earn that in two hours selling weed etc. By the morning the police had come into my flat and arrested me. I woke up dazed and confused with a hangover from hell and realised I was in a police station. I had no idea how I had got there or why I was there. I got on the bell and ask them, and then I was told, I quote, you were brought in for armed robbery. I had no need to do what I did that night.

I cannot tell you why or what I did it for because I’ve been asking myself that for many years now.

I’m just glad I never hurt anyone that night. I’m trying to write to the shopkeeper through probation to ask for his forgiveness and do what I can to apologise. Any trauma I might have caused that night. Sadly, by the time I realised I needed to do this. It was too late. I was given an 18-year sentence for that on a guilty plea. So, the judge would have given me around 25 years for that. It was a determinate sentence without my guilty credit taken off. However, I was to become an IPP prisoner, so the 18 years would be halved, and a tariff would be put on it. I did appeal and got this taken to a 4½ year sentence. So, all I would have to do is keep my head down, do some courses and take the rehabilitation offered. I’d be out in four and a half, right?

I was like a lamb to the slaughter. Little did I know then the world of hate, pain, violence, despair, I will be thrown into.

On reflection now, it’s actually quite hard for me to put into words how I got to the place I’m at now physically and mentally. It’s not isolated to one place of fault or blame, there is so many different factors that contribute to the IPP crisis that I see today. Also, everyone is different, some can endure more than others. But the one thing that I am certain of is that it is the repetition of trauma that is most damaging. Trauma is trauma, we go through it and depending on what level of trauma one endures it’s about being able to deal with that, having the time, help, support and space to do so and heal.

The problem with the IPP is that every single thing needed to go through the healing process is not accessible and furthermore, over time we go through it again and again until we become a product of the environment, we can’t escape.

This trauma then becomes torture and the strangest thing of all is the people who create or enforce this way of life then take no responsibility for doing so. When a broken man sits in front of them they blame the man for indeed breaking.

Due to government cuts on prison staff, education, etc. wings are flooded with drugs, kilos coming in on drones on a nightly basis. An addict then comes to prison. But little does he know that he’s just swapping one drug house for another. And in this drug house, drugs are cheaper, and he hasn’t got to go shoplifting to get money to use. Then when he has a piss test, he is punished for using drugs. The prisoner estate covers everything up, they will portray that yeah, there is the problem, there always will be, but we’re working on it. When the truth is the whole system is burning with flame from hell, they have an obligation to provide criminals with drug free environments to progress, yet they will punish an addict for using drugs when it is the prison who has served it to them on a plate. It’s like telling an alcoholic not to drink but making him live and sleep in a bar. I’m sorry I’m digressing somewhat though. There is just so many systematic failures that contribute to the prison crisis that we live and see today.

As a normal prisoner, it is hard enough like I said at the start, but as an IPP is a soul-destroying environment to live in. Using a similar comparison as a drug addict, as IPPs we were told that under no circumstances can we get involved in violence. This is a big no no, yet the wings are some of the most violent places you have ever seen.

Do not let anyone fool you.

I have lived it and seen it for too long now. The things that I have witnessed are truly things of horror films. To be able to navigate yourself through this for years is so difficult. The social dynamics on wings is not the same as in the community. If faced with any confrontation, you only have three choices.

1. You submit and hope for the best, but now you are weak among your peers.

2. You stand your ground which can result in death or being slashed or stabbed.

3. Which is what the prison would expect you to do, go to staff and tell them. Now you’re a snitch and a target from everyone.

They are the only choice you have in an environment that is ever growing more violent and dangerous by the minute. I fear to see how things will be in years to come.

We as IPPs are put in impossible positions and as the years go by, the worse it gets.

And the more trauma we endure again and again. That in my opinion, is why so many IPPs now are suffering with PTSD, drug abuse, personality disorders, etc. The system has destroyed them and will continue to do so until people push for change.

There is only one resolution in my opinion, and that the Justice select committee had its spot on. Government needs to face facts and, on some level, admit what everyone else seems to know and that is that the system failed to rehabilitate them in the start, failed to rehabilitate during, and is failing to do so now 10 years after the abolition.

To the ones who remain that are sinking deeper and into hopelessness, freedom is indeed the only Saviour now.

I myself have luckily not let it beat me to the point of insanity or death, although some may disagree.

I decided to take a stand when it matters, when Dominic Raab knocked back the resentencing proposals.

Instead of letting it break me any further,

I commenced a roof top protest in Manchester that went viral on most social platforms.

It was costly to my so-called progression, but it was a sacrifice I had to take.

For too long government have ignored or covered up the injustice of the IPP, so many agreeing with how wrong it was and how it should never have happened yet taking no action themselves to bring change. Cheap words is all.

Well, I took the choice to shine a light on it and not let them hide.

I did a 12-hour protest for not only myself and all those still on IPP, but for all them families of the 81 lost souls.

All them must be held accountable who contributed to the failures that led to them poor people taking them lives. Even if it is for 12 hours, the support and love that I have received since then, has been overwhelming, at times truly beautiful.

Well after that I was sent to HMP Frankland, where their intention to punish me for my activism was made clear by the foul things they did to me in that segregation. They refused to give me my special NHS diet that I had had for over four years due to my health, starved me, then one day while moving me cell, jumped on me and began assaulting me. I was stripped naked and placed in a box cell for hours on end. Right there and then, I decided, I was not going to take been treated this way. Days later I went out on the yard and managed to scale the wall. I then use a CCTV camera to break the cage roof and escape the seg, becoming the only man to ever escape a cat A segregation in the UK.

I then got my own back for the weeks of bully boy treatment and abuse by smashing the place to pieces. Then having a nice sunbathe in my boxers. This made the papers again, so now in eight weeks I’ve scaled 2 roofs and I’ve been in the press in countless papers. For this level of exposure,

I have now been sent to HMP Belmarsh unit segregation, where I stay totally isolated from everyone.

I get what I have done embarrass the prison state, but some would say it was a long time coming. I stand up for what I believe in and I know my values and principles. I should be proud of decency, respect, honesty, loyalty, humility, and dignity. It is the system that lacks in these principles, not me. In 13 years I have not once assaulted a member of staff yet I’ve been battered, stabbed, had my nose broken, lit split, teeth knocked out and that is just the physical abuse. Yet despite all this I shall keep my resolve.

My life now consists of exercise with four screws, a dog unit and I’m handcuffed and made to wear flip flops. Anyone would think I’m Bruce Lee. Some would say justified I’ll leave that up to you.

Since being here I’ve been subjected to over 170 full body strip searches in 14 weeks, sometimes four or more a day for three months. I was told all my visit rights had been stopped. Thankfully, they developed a change of heart and I now get visits. When will they let me back on the wings. I don’t know how long until I see a person’s face in this place that’s not a staff member, I also don’t know.

What I do know is that try as they might, my spirit will not be broken.

There is a movement out there that I am part of which gives me such strength and resolve. The other day I heard a man’s voice that I’ve never met being played to me down the phone by my girlfriend. This man spoke in a demo outside the prison about my story and all the IPPs, I love that, I felt through that voice I’ve never felt better. I was instantly elevated and overwhelmed. I used to feel lost, I used to feel lonely.

But now while I sit in the most lonely, isolated part of a prison system I am loved, I am supported, and I am strong.

But there are many, many more that sadly are not and for them I hope they find strength.

Kindness and love always.

Joe outlaw

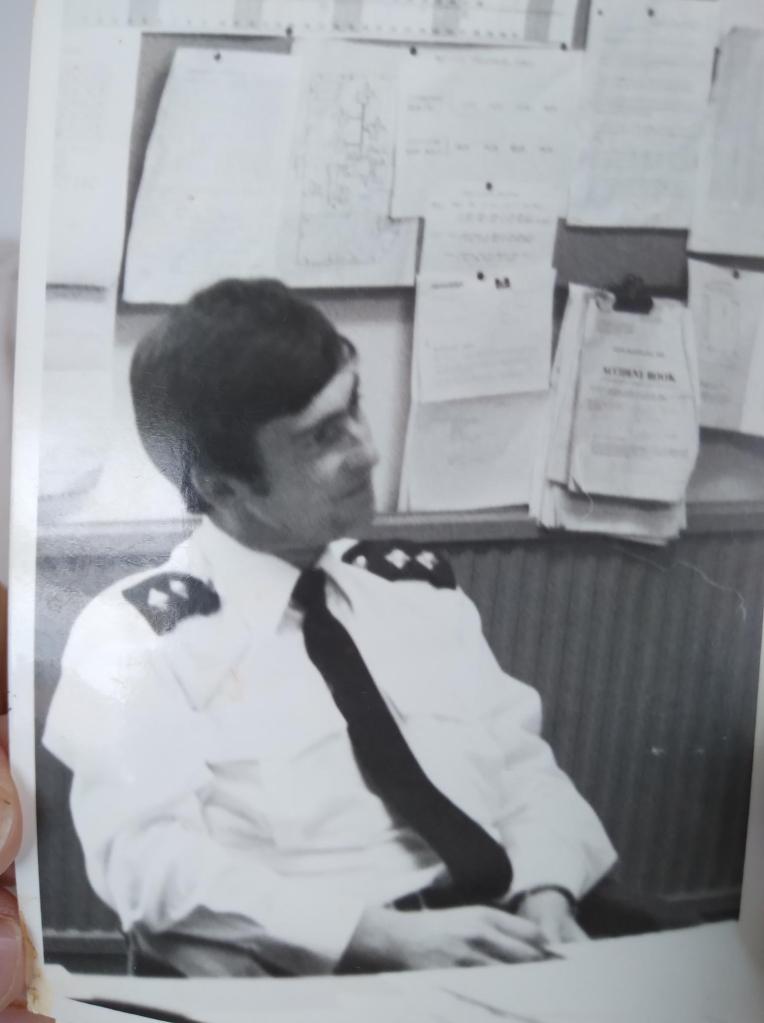

Guest blog: Being visible: Phil O’Brien

An interview with Phil O’Brien by John O’Brien

Phil O’Brien started his prison officer training in January 1970. His first posting, at HMDC Kirklevington, in April 1970. In a forty-year career, he also served at HMP Brixton, HMP Wakefield, HMYOI Castington, HMP Full Sutton, HMRC Low Newton and HMP Frankland. He moved through the ranks and finished his public sector career as Head of Operations at Frankland. In 2006, he moved into the private sector, where he worked for two years at HMP Forest Bank before taking up consultancy roles at Harmondsworth IRC, HMP Addiewell and HMP Bronzefield, where he carried out investigations and advised on training issues. Phil retired in 2011. In September 2018, he published Can I Have a Word, Boss?, a memoir of his time in the prison service.

John O’Brien holds a doctorate in English literature from the University of Leeds, where he specialised in autobiography studies.

You deal in the first two chapters of the book with training. How do you reflect upon your training now, and how do you feel it prepared you for a career in the service?

I believe that the training I received set me up for any success I might have had. I never forgot the basics I was taught on that initial course. On one level, we’re talking about practical things like conducting searches, monitoring visits, keeping keys out of the sight of prisoners. On another level, we’re talking about the development of more subtle skills like observing patterns of behaviour and developing an intimate knowledge of the prisoners in your charge, that is, getting to know them so well that you can predict what they are going to do before they do it. Put simply, we were taught how best to protect the public, which includes both prisoners and staff. Those basics were a constant for me.

Tell me about the importance of the provision of education and training for prisoners. Your book seems to suggest that Low Newton was particularly successful in this regard.

Many prisoners lack basic skills in reading, writing and arithmetic. For anyone leaving the prison system, reading and writing are crucial in terms of functioning effectively in society, even if it’s only in order to access the benefits available on release.

At Low Newton, a largely juvenile population, the education side of the regime was championed by two governing governors, Mitch Egan and Mike Kirby. In addition, we had a well-resourced and extremely committed set of teachers. I was Head of Inmate Activities at Low Newton and therefore had direct responsibility for education.

The importance of education and training is twofold:

Firstly, it gives people skills and better fits them for release.

Secondly, a regime that fully engages prisoners leaves less time for the nonsense often associated with jails: bullying, drug-dealing, escaping.

To what extent do you believe that the requirements of security, control and justice can be kept in balance?

Security, control, and justice are crucial to the health of any prison. If you keep these factors in balance, afford them equal attention and respect, you can’t be accused of bias one way or the other.

Security refers to your duty to have measures in place that prevent escapes – your duty to protect the public.

Control refers to your duty to create and maintain a safe environment for all.

Justice is about treating people with respect and providing them with the opportunities to address their offending behaviour. You can keep them in balance. It’s one of the fundamentals of the job. But you have to maintain an objective and informed view of how these factors interact and overlap. It comes with experience.

What changed most about the prison service in your time?

One of the major changes was Fresh Start in 1987/88, which got rid of overtime and the Chief Officer rank. Fresh Start made prison governors more budget aware and responsible. It was implemented more effectively at some places than others, so it wasn’t without its wrinkles.

Another was the Woolf report, which looked at the causes of the Strangeways riot. The Woolf report concentrated on refurbishment, decent living and working conditions, and full regimes for prisoners with all activities starting and ending on time. It also sought to enlarge the Cat D estate, which would allow prisoners to work in outside industry prior to release. Unfortunately, the latter hasn’t yet come to pass sufficiently. It’s an opportunity missed.

What about in terms of security?

When drugs replaced snout and hooch as currency in the 1980s, my security priorities changed in order to meet the new threat. I had to develop ways of disrupting drug networks, both inside and outside prison, and to find ways to mitigate targeted subversion of staff by drug gangs.

In my later years, in the high security estate, there was a real fear and expectation of organised criminals breaking into jails to affect someone’s escape, so we had to organise anti-helicopter defences.

The twenty-first century also brought a changed, and probably increased, threat of terrorism, which itself introduced new security challenges.

You worked in prisons of different categories. What differences and similarities did you find in terms of management in these different environments?

Right from becoming a senior officer, a first line manager at Wakefield, I adopted a modus operandi I never changed. I called it ‘managing by walking about’. It was about talking and listening, making sure I was there for staff when things got difficult. It’s crucial for a manager to be visible to prisoners and staff on a daily basis. It shows intent and respect.

I distinctly remember Phil Copple, when he was governor at Frankland, saying one day: “How do you find time to get around your areas of responsibility every day when other managers seem tied to their chairs?” I found that if I talked to all the staff, I was responsible for every day, it would prevent problems coming to my office later when I might be pushed for time. Really, it was a means of saving time.

The job is the same wherever you are. Whichever category of prison you are working in, you must get the basics right, be fair and face the task head on.

The concept of intelligence features prominently in the book. Can you talk a bit about intelligence, both in terms of security and management?

Successful intelligence has always depended on the collection of information.

The four stages in the intelligence cycle are: collation, analysis, dissemination and action. If you talk to people in the right way, they respond. I discovered this as soon as I joined the service, and it was particularly noticeable at Brixton.

Prisoners expect to be treated fairly, to get what they’re entitled to and to be included in the conversation. When this happens, they have a vested interest in keeping the peace. It’s easy to forget that prisoners are also members of the community, and they have the same problems as everyone else. That is, thinking about kids, schools, marriages, finances. Many are loyal and conservative. The majority don’t like seeing other people being treated unfairly, and this includes prisoner on prisoner interaction, bullying etc. If you tap into this facet of their character, they’ll often help you right the wrongs. That was my experience.

Intelligence used properly can be a lifesaver.

You refer to Kirklevington as an example of how prisons should work. What was so positive about their regime at the time?

It had vision and purpose and it delivered.

It was one of the few jails where I worked that consistently delivered what it was contracted to deliver. Every prisoner was given paid work opportunities prior to release, ensuring he could compete on equal terms when he got out. The regime had in place effective monitoring, robust assessments of risk, regular testing for substance abuse and sentence-planning meetings that included input from family and home probation officers.

Once passed out to work, each prisoner completed a period of unpaid work for the benefit of the local community – painting, decorating, gardening etc.

There was excellent communication.

The system just worked.

The right processes were in place.

To what extent do you feel you were good at your job because you understood the prisoners? That you were, in some way, the same?

I come from Ripleyville, in Bradford, a slum cleared in the 1950s. Though the majority of people were honest and hardworking, the area had its minority of ne’er-do-wells. I never pretended that I was any better than anyone else coming from this background.

Whilst a prisoner officer under training at Leeds, I came across a prisoner I’d known from childhood on my first day. When I went to Brixton, a prisoner from Bradford came up to me and said he recognised me and introduced himself. I’d only been there a couple of weeks. I don’t know if it was because of my background, but I took an interest in individual prisoners, trying to understand what made them tick, as soon as I joined the job.

I found that if I was fair and communicated with them, the vast majority would come half way and meet me on those terms. Obviously, my working in so many different kinds of establishments undoubtedly helped. It gave me a wide experience of different regimes and how prisoners react in those regimes.

How important was humour in the job? And, therefore, in the book?

Humour is crucial. Often black humour. If you note, a number of my ex-colleagues who have reviewed the book mention the importance of humour. It helps calm situations. Both staff and prisoners appreciate it. It can help normalise situations – potentially tense situations. Of course, if you use it, you’ve got to be able to take it, too.

What are the challenges, as you see them, for graduate management staff in prisons?

Credibility, possibly, at least at the beginning of their career. This was definitely a feature of my earlier years, where those in the junior governor ranks were seen as nobodies. The junior governors were usually attached to a wing with a PO, and the staff tended to look towards the PO for guidance. The department took steps to address this with the introduction of the accelerated promotion scheme, which saw graduate entrants spending time on the landing in junior uniform ranks before being fast-tracked to PO. They would be really tested in that rank.

There will always be criticism of management by uniform staff – it goes with the territory. A small minority of graduate staff failed to make sufficient progress at this stage and remained in the uniform ranks. This tended to cement the system’s credibility in the eyes of uniform staff.

Were there any other differences between graduate governors and governors who had come through the ranks?

The accelerated promotion grades tended to have a clearer career path and were closely mentored by a governor grade at HQ and by governing governors at their home establishments and had regular training. However, I lost count of the number of phone calls I received from people who were struggling with being newly promoted from the ranks to the governor grades. They often felt that they hadn’t been properly trained for their new role, particularly in relation to paperwork, which is a staple of governor grade jobs.

From the point of view of the early 21stC, what were the main differences between prisons in the public and private sectors?

There’s little difference now between public and private sector prisons. Initially, the public sector had a massive advantage in terms of the experience of staff across the ranks. Now, retention of staff seems to be a problem in both sectors. The conditions of service were better in the public sector in my time, but this advantage has been eroded. Wages are similar, retirement age is similar. The retirement age has risen substantially since I finished.

In my experience, private sector managers were better at managing budgets. As regards staff, basic grade staff in both sectors were equally keen and willing to learn. All that staff in either sector really needed was purpose, a coherent vision and support.

A couple of times towards the end of your book, you hint at the idea that your time might have passed. Does your approach belong to a particular historical moment?

I felt that all careers have to come to an end at some point and I could see that increasing administrative control would deprive my work of some of its pleasures. It was time to go before bitterness set in. Having said that, when I came back, I still found that the same old-fashioned skills were needed to deal with what I had been contracted to do. So, maybe I was a bit premature.

My approaches and methods were developed historically, over the entire period of my forty-year career. Everywhere I went, I tried to refine the basics that I had learned on that initial training course.

Thank you to John O’Brien for enabling Phil to share his experiences.

~

A conversation with: Barry Thacker, Deputy Chief of Police, The Falklands, South Georgia, and South Sandwich Islands

Introduction

It’s May 1982, holidaying in Somerset, where new friendships in the making were overshadowed by the Falklands War. Faith, Pam, Mark, Sally, Denise and Barry …

Each day we bought and read together the Times newspaper, the broadsheet format detailing the horrors of war, the loss, the gains, the heartbreak of lives sacrificed, the images of destruction. The Falklands War will forever be etched in my memory. We all kept in touch for a few years, but then we all went our separate ways.

Fast forward almost 40 years.

I’m sat at my computer engaging in a zoom conversation with Barry Thacker, Deputy Chief of Police of the Falkland Islands. Reminiscing about that holiday back in 1982. Barry was 18, I was 17 with our lives ahead of us. Never knowing that all these years later our paths would cross again.

Remarkable.

Tell me a little about your family background.

I am from a small mining village on the Derbyshire/Nottinghamshire border. My dad, a miner all his life, died prematurely at 69 with pneumoconiosis. My mum is still going well at 90. I am the youngest of 4 and had a comprehensive education. Life was a little tough during 1984 and the UK miners’ strike but as a family we got through it. My wages kept us and some friends afloat.

When you left school what was your first job?

Fruit and veg assistant at a local wholesaler. It was where I met Ivan Bamford, my supervisor, who was a special constable. After a few weeks, an opportunity arose on a government YTS (Youth Training Scheme) at the police station, I felt it would give me experience into a career I really wanted to pursue. It wasn’t long into the YTS that I was taken on full time as an admin clerk and when I hit 18 there was no recruitment so I joined the Derbyshire Special Constabulary working for Ivan again.

Why were you unsuccessful in joining the Police Cadets, did you ever think of giving up and choosing a different path?

I know it is a cliché, but I always wanted to be a cop after receiving a police pedal car for Christmas one year. When I left school there were still paid police cadets, so when I was in the 5th year (Y11 now) as Nottinghamshire police were recruiting cadets, I applied and was successful with the entrance exam. However, I wasn’t successful in my ‘O’ level (GCSE) English so was told to wait until I was 18 and try straight for the regular police.

You eventually started working for the police by finding another route. Do you think that part of your character is to not give up but find alternatives to situations?

I am a big believer in things happening for a reason and although not knowing at the time as you reflect on your life things become evident. Whatever setbacks we have in life I always try to see the good and by entering the police at the bottom, so to speak, I can appreciate the frustrations of all ranks. It is that emotional intelligence which I like to think has got me to where I am today looking after the policing for 3 overseas territories, The Falklands, South Georgia, and South Sandwich Islands.

You were presented with a silver baton, explain what that was for.

I attended my initial 14-week training at Ryton on Dunsmore police college. As it had taken me many setbacks to get where I wanted to be I was determined to prove myself, I focused my efforts and became class leader and never scored less than 90% on my weekly and course exams. At pass out I was awarded the Commandant’s baton for top student on the course.

My initial posting as a regular PC was the East of Derby City, a multicultural deprived area of the city.

Being brought up in a small Derbyshire town was a far cry from working in Derby. What were some of the challenges you faced?

The innocence and trust I was used to in a small village was a far cry from inner city Derby. I wasn’t averse to deprivation and need but the support of a village wasn’t always there in an often faceless city.

It was my first time away from home, living in a small council owned flat. Initially I had litter, food and other unmentionables posted through my letter box, everyone knew it was a police flat. The anti-social behaviour towards me was short lived, I became established in the estate, I think like life in general it’s very much how you interact and deal with people that gets you results; yes, I was a cop, but I was their cop and they often sought my advice ‘off the record’ but with the understanding I was still a cop and on occasions had to take action on what they told/asked me.

Over your 32-year career with Derbyshire Constabulary, you received 8 commendations for your work. Can you expand on a few?

As a young cop I was sent to a boy/girl friend splitting up and when I arrived the young man had poured petrol over the girl’s car and was going to set it alight. Following a struggle which resulted in us both getting covered in petrol from the can he had used I had, for the first and only time in my career, struck someone with my truncheon – proportionate force – to make him release the lighter he was trying to use to set us and the car alight.

A businessman was kidnapped as he left his factory in Leicester and driven to Birmingham with a demand for £1.5m from his family for his safe release. I was appointed negotiator coordinator for the 5 counties of the East Midlands and had to staff this incident through mutual aid between all the forces, as well as maintain trained negotiators to respond to others calls for negotiator input. At one stage I was managing the kidnap in Leicester and 2 suicide interventions in Nottinghamshire and Northampton. This was I think one of the most stressful yet rewarding parts of my career, saving all lives. The 3 offenders from the kidnap received a total of 90 years imprisonment.

You received a Certificate in Counter Terrorism from St Andrews in 2007, what led you to study?

As part of my role as County Partnership Inspector, part of my portfolio was that of the prevent part of the government’s Contest anti-terrorism agenda, the other parts being prepare, pursue, and protect. I had to coordinate police and partner agency resources to prevent the threat of terrorism within the county. So, to increase my knowledge and support my role as a Home Office terrorism trainer, I did the course.

Serving 32 years with the Derbyshire Constabulary is quite a commitment

Yes, I had some good times with amazing people and some truly inspiring leaders. The police service isn’t just a job but a calling, a family atmosphere of mutual respect and willingness to help and support each other; there are some terrible incidents officers witness. I’ve had numerous ones. For example, I’ve been handed a severed head in a carrier bag, you need that support to get you through. There is a lot of media negativity and society kick back to the police, but we are the ones who are there to always give that help and support to others putting our own feelings aside until the job is done.

You took retirement around your 50th birthday. Did you plan it that way?

That is the way the police pension works; you pay in 14% of you pay throughout your 30-year career to retire at this age. I did the extra 2 years to establish a project I started of a multi-agency web-based information sharing system.

From having active roles in the community for so long how did it feel for that chapter in your life to close?

It was difficult and takes time to get over the fact you have no powers, handing over my warrant card after so long was a big thing. But the constabulary try to prepare you and, as I have said previously, the support of family and network of friends gets you through it.

How important has it been for you during your police career to be authentic?

I owe a lot to my humble beginnings and how my parents raised me and the standards and morals they instilled in me. My faith has been tested at times but I have always come through and grown through life lessons; at times it was the only thing keeping me going.

Retirement did not last long as you “missed the buzz of the Police” So, you applied for a very unusual position, far away from friends and family and initially became Senior Constable with the Royal Falklands Police on a 2-year placement. So, what changed as you are still there?

I saw the advert on LinkedIn and fancied an adventure and the experience of a Southern Hemisphere life. I also thought of the experience I could bring to the role and so an enriched service to the community. I thought what an opportunity to forget about budgets, staffing, politics, policies, etc and returned to the role of Constable where I started many years ago.

The Falkland Islands is a truly awesome location. The scenery, wildlife, sunrises and sunsets, and amazing stars at night together with a lovely community. So a 2-year contract was signed. After just 9 months I was promoted to deputy Chief of Police and a further 2 year contract was signed, so I’m currently in my 3rd year here finishing at the end of 2022. Then let’s see what the next chapter of my life has in store.

I have had the privilege of meeting the Chiefs of the other Overseas Territories and I feel blessed to be looking after the ones I do, but who knows? Maybe somewhere a tad warmer next?

How different is policing on the Falkland Islands?

I have policed deprived areas, I’ve policed affluent areas, and everywhere in between. Each area is unique and there is good everywhere, sometimes a tad more difficult to find but it will always be there. The Falkland Islands has a population of around 3,000 (by comparison Derbyshire Constabulary had more staff working for them) is very much a community that people reminisce of; the community is great and most people know each other.

There is very little aquisitive crime and people are honest and genuinely care about their lifestyle, each other, and the environment they share with the wildlife. There is also a military camp and I have developed an exceptional working relationship with them, something I couldn’t have done in the UK and the experiences I would never have been exposed to in the UK.

Being personal friends with His Excellency The Governor and his wife are, again, the sort of opportunities I couldn’t even dream about in the UK. However, with the island being so law abiding, any breaches of the law are magnified in ways which they never would be in the UK.

I am very much aware of the privileged position I hold and the additional restrictions that puts on my social life in addition to those of a regular police officer.

You once wrote “I am passionate about community work especially giving a voice to the most vulnerable and believe in the encouragement and mentoring of young people helping them to achieve their full potential” how are you able to put this into practice where you are now?

I continue to believe in community which I hope I have demonstrated throughout this conversation. During my time as Senior Constable here I took on the role of school liaison. I have been able to be there for these young people, helping them continue their studies in the UK and have enjoyed watching some of them grow into independent adults.

If I can help guide and break down any barriers between young people and the police then that must be a good job – as with the rest of the community – to be appreciative of their lives, to take an interest but be firm and fair; enforcing the law without fear or favour, malice, or ill will.

To summarise I have had a fulfilled career as a UK officer and still doing the job I love helping and supporting people in need.

We all carry hang ups, problems and insecurities and not everyone knows how to deal with their own issues and interactions with others. Someone once told me people will forget what you say to them but not how you make them feel.

Compassion and understanding go a long way to endear us to each other.

~

All photographs used with the kind permission of Barry Thacker

~

HMP Berwyn: Does it raise more questions than it answers? Part 2

The Wales Governance Centre, a research centre and part of Cardiff University’s School of Law and Politics undertakes innovative research into all aspects of the law, politics, government and political economy of Wales.

This week they released a report: Sentencing and Imprisonment in Wales 2018 Factfile by Dr Robert Jones

Before looking at this report, lets put things in context by referring to the first unannounced inspection by HMIP of HMP Berwyn in March 2019. Here it is reported that “impressive” support procedures are in place for new arrivals. Positive note. However, use of force was considerably higher than at similar prisons and 1 in 4 prisoners (23%) told HMIP that they felt unsafe. Alarm bells?

Below are the four tests when inspecting a prison, Safety, Respect, Purposeful activity and Rehabilitation and release planning. Not the best outcome for the first inspection.

Safety: Outcomes for prisoners were not sufficiently good against this healthy prison test.

Respect: Outcomes for prisoners were reasonably good against this healthy prison test.

Purposeful activity: Outcomes for prisoners were not sufficiently good against this healthy prison test.

Rehabilitation and release planning: Outcomes for prisoners were not sufficiently good against this healthy prison test.

HMP Berwyn prison has only been open just over 2 years, hasn’t reached full capacity and has its 3rd governing Governor.

Now let’s look at some of the facts revealed that are not easy reading

The number of self-harm incidents

2017 = 231

2018 = 542

Self-harm incidents rose by 135% in 2018

Rate of self-harm: (48 per 100 prisoners)

This is what the Government website states:

“Self-harm may occur at any stage of custody, when prisoners are trying to deal with difficult and complex emotions. This could be to punish themselves, express their distress or relieve unbearable tension or aggression. Sometimes the reason is a mixture of these. Self-harm can also be a cry for help, and should never be ignored or trivialised” https://www.gov.uk/guidance/suicide-self-harm-prevention-in-prison

This is what the HMIP report states:

“The strategic management of suicide and self harm required improvement. Strategic meetings were poorly attended and too little was done to analyse, understand and take action to address the causes of self-harm. Most of the at-risk prisoners on assessment, care in custody and teamwork (ACCT) case management did not feel sufficiently cared for. ACCT documents required improvement, and initial assessments and care plans were weak”

Yet below are more uncomfortable facts showing that this prison is not just dangerous for prisoners but for staff too. Nothing to celebrate here.

The number of prisoner-on-prisoner assaults rose by 338% in 2018

Rate of prisoner-on-prisoner assaults: (20 per 100 prisoners)

The number of assaults on staff at HMP Berwyn increased by 405% in 2018

Rate of recorded assaults on staff (18 per 100 prisoners)

You would think that a new prison would have a security department second to none, with little chance of items being brought in. Yet these figures show that weapons, drugs, alcohol and tobacco are increasingly being found. Some may say hats off to the staff for finding these items, but really there’s still no cause for celebration…

The number of incidents where weapons were found in prison, years ending

March 2017 = 1

March 2018 =25

March 2019 Berwyn = 138

The rate of weapon finds (11 per 100 prisoners) year ending March 2019

This was the highest rate per prisoners in all prisons in Wales, astonishing. Serious problems with security.

The number of drug finds at HMP Berwyn increased by 328% in the year ending March 2019 (prison population increased by 67% during this period)

The rate of drug finds (16 per 100 prisoners)

Where are the robust measures to stop drugs coming into the prison?

The number of incidents where alcohol was found in HMP Berwyn years ending March

2017 = 0

2018 = 21

2019 = 146

Alcohol finds at HMP Berwyn rose by 595% (prison population increased by 67% during this period)

Rate of alcohol finds (12 per 100 prisoners) year ending March 2019.

Yet again the highest rate of alcohol finds in all the prisons in Wales

The number of incidents where tobacco was found in HMP Berwyn years ending March

2018 = 20

2019 = 61

Rate of tobacco finds (5 per 100 prisoners)

The prison is covered in photos of Wales and the countryside, everywhere you look there is a motivational quote, there are flowers, bees, greenhouses yet one in 4 prisoners didn’t feel safe.

Comfy chairs in reception, pretty pictures, colourful décor does not appear to contribute to the safety of HMP Berwyn.

Motivational quotes such as “When a flower doesn’t bloom you fix the environment in which it grows not the flower” means nothing if a quarter of the population feel unsafe.

Prisons can be austere places, drab, filthy, old and not fit for purpose. But here we have a new prison with serious problems. There can be no excuse that these are teething problems, we are talking about peoples lives.

Remember the Berwyn Values?

V = value each other and celebrate achievements

A = act with integrity and always speak the truth

L = look to the future with ambition and hope

U = uphold fairness and justice in all we do

E = embrace Welsh language and culture

S = stick at it

Is this just a marketing ploy, designed for a feel-good factor, making us all think that the money spent on this Titan prison was worth every penny?

Independent monitors have praised the work of staff at HMP Berwyn describing their efforts to establish a new prison as a ‘considerable achievement” (Recent comment by IMB) After this shocking report, what will they now say? Or will they remain silent?

I don’t doubt there are some hard working, diligent and caring staff. In fact, I met some on my visit last year. But when the prison opened in 2017 over 90% of staff had never worked in a prison before. When you have prisoners arriving from over 60 prisons all with different regimes, you find they have far more experience of the prison estate than the majority of prison officers.

But more worryingly is that the Government is continuing with its programme of building new prisons. A new prison will be built in Wellingborough as part of the Government’s Prison Estate Transformation Programme. I’ve read gushing articles on how this prison will benefit the community etc, similar to when HMP Berwyn began construction. Just like HMP Berwyn there are many promises and opportunities, but theory and practice can be a million miles apart.

Where’s Mum?…she’s in prison with an author and an actor off Eastenders!

Daughter: Did you just say Mum’s visiting a prison in London with an author and an actor off Eastenders ?

Son 1: If I stop someone from killing someone else and in so doing I kill them, am I a bad person or is it just what I have done bad?

Son 2: Did you really sit in a room with prisoners, what if they were murderers?

Boyfriend of daughter: Wow, you were in the audience and sat with prisoners?

Are these the kind of conversations you have with your family?

Over the past four years I have met many prisoners who all had one thing in common: they just needed someone to believe in them, to listen to them and to help them whilst in prison and once their sentence had ended.

I’ve found that, for some of them, criminal activity had become a way of life; they knew nothing else and would most likely continue in the same way after release. For others, falling into crime was a result of a stupid decision or action, often spontaneous, which had got them in to trouble with the law, convicted and sent to prison; they felt a debilitating remorse and that they had let themselves and their families down.

Crisis – what crisis?

We read that the prison population continues to rise, overcrowding in prison seems to be the norm rather than the exception and violence, suicides and self-harm are weekly occurrences. There is tragedy after tragedy yet we are told that there is no crisis in our prison system.

So what should we do? One solution is to accept the status quo and keep our heads in the sand. Another is to actually address the issues. But, as I keep hearing, this has to be a coherent team effort.

Not settling for the status quo

In January, I visited a London prison and was accompanied by NoOffence! Patron, actor Derek Martin (Eastenders’ Charlie Slater) and author Jonathan Robinson (@IN_IT_THE_BOOK) from their Advisory Board. I’ve already blogged about the visit and the lessons I took away from that experience.

At a peer mentoring conference last year, I met with Rob Owen OBE the chief executive of St Giles Trust, an Ambassador for NoOffence!

St Giles Trust aims to help break the cycle of prison, crime and disadvantage and create safer communities by supporting people to change their lives.

Next week, I will be meeting Geoff Baxter OBE the CEO of Prison Fellowship who is also an Ambassador of NoOffence!

This is just a small sample of the organisations that work to improve the lives of offenders, there are many more.

I’d dearly like to explore how these organisations can find more ways to work together; these plus leaders such as Howard League perform outstanding work as organisations in their own right. Just imagine what could be achieved if new ways of working could be agreed to improve the Criminal Justice System.

In December 2012 I was accepted by the Secretary of State to the Independent Monitoring Board (IMB) of an open prison. To carry out my duties effectively, the role provide the right of access to every prisoner and every part of the prison I monitor, and also to the prison’s records. Independent monitoring ensures people in custody are treated fairly and humanely; I take this work very seriously.

When I started working in prisons it was as a group facilitator for Sycamore Tree, a victim awareness programme teaching the principles of restorative justice. For many offenders on Sycamore Tree one of the most powerful element of the programme is when a victim of crime visits to talk with the group how crime has impacted their lives. In week 6 of the programme, participants have an opportunity to express their remorse – some write letters, poems or create works of art or craft. Members of the local community are invited to the course to observe the many varied symbolic acts of restitution.

I’ve seen some remarkable lives turned around among offenders who make it to this stage of the programme. Okay, you argue, there is no way these outcomes can be achieved in 100% of cases. I agree.

But programmes that provide education and encouragement have to be a more purposeful activity and more effective towards increasing the chances of better outcomes with more offenders than them simply being banged up for 23 hours a day with the TV.

But all it takes is a bit of coherent team work.

I like what NoOffence! says in their mission statement and vision:

Mission Statement: NoOffence! will encourage, promote and facilitate the collaboration of organisations from the voluntary, public and private sectors to address the issue of reducing crime and reoffending.

Vision: To be the leading online criminal justice communication, information exchange and networking community in the world. Our vision for NoOffence! has always been to bring justice people together to overcome barriers to rehabilitation. We believe the solution to complex justice problems lie with the people…

They have got a point, haven’t they?

I for one would be open to try to forge more collaboration than we see today. And I know I’m not alone in that view; many others are prepared to voice a similar willingness and appetite for supporting each other.

Actions speak louder than words. Let’s get on with it.

Continue the conversation on Twitter #rehabilitation

Evolution of Peer Power

It was a privilege to be a delegate at the No Offence! Evolution of Peer Power ‘The new revolution in breaking the cycle of offending’ conference in London on 18th September.

It was designed to celebrate peer mentoring as good practice and to give prominence to the achievements of both peer mentors and their clients.

There has in recent years been a lot of talk about breaking the cycle of offending. We all waited with bated breath for the governments’ launch of the green paper in December 2010 ‘Breaking the Cycle Effective Punishment, Rehabilitation and Sentencing of Offenders’. This Green Paper set out plans for fundamental changes to the criminal justice system in order to break the destructive cycle of crime, meaning that more criminals make amends to victims and communities for the harm they have caused. In so doing create a rehabilitation revolution that will change those communities whose lives are made a misery by crime. However, the criminal justice system is relied upon to deliver the response of: punishing offenders, protecting the public and reducing re-offending. This Green Paper addressed all three of these priorities, setting out how an intelligent sentencing framework, coupled with more effective rehabilitation, will enable the cycle of crime and prison to be broken.

So where does mentoring fit in? Well it is mentioned twice,

139. We have already launched the Social Impact Bond in Peterborough prison focused on those offenders serving less than 12 months in custody. Social investors are paying up front for intensive services and mentoring delivered by the voluntary and community sector. We will pay solely on the results they deliver.

266. In line with our broader reforms on transparency we also believe that local communities should know how their local youth justice services are performing, and have an opportunity to be involved. Both Youth Offending Teams and secure estate providers significantly involves volunteers to support the work that they do; there are approximately 10,000 volunteers already working within the youth justice system. This includes participation as youth offender panel members and mentors. We want to build on this, including encouraging voluntary and community sector providers, where appropriate, to deliver services. We also intend to publish more data at local level so that communities can see the effectiveness of their local Youth Offending Team for themselves, and use this information to inform and shape local priorities.

Let’s move forward 4 years……..

Offender Rehabilitation Act 2014

An Act to make provision about the release, and supervision after release, of offenders; to make provision about the extension period for extended sentence prisoners; to make provision about community orders and suspended sentence orders; and for connected purposes. [13th March 2014].

So yet again we consider where mentoring fits in the overall scheme of rehabilitation and breaking the cycle of offending. According to Rob Owen Chief Executive, St Giles Trust, highly motivated, uniquely credible, well-trained and well-managed, ex offender Peer Advisors deliver a professional, high calibre, impactful service to help other ex offenders through peer-led support. With each £1investment in peer mentoring the tax payer saves £10, sounds like good value for money.

Former Cabinet Minister, Author and prison reform campaigner Jonathan Aitken, stated that:

“Rehabilitation is falling off the agenda within prisons” and “mentoring needs to start in prison and not at the gate”.

However, with the Transforming Rehabilitation programme, it is hoped that this is not the case as mentoring is now on the agenda.

Ministry of Justice (2010) Breaking the cycle: Effective Punishment, Rehabilitation and Sentencing of Offenders. London: TSO. (Cm. 7972).

Fighting crime with algorithms

Algorithms have been used by the police identify crime hot spots in Memphis, Tennessee since 2005. Under the code name of Operation Blue Crush, from 2005 to 2011 crime has dropped by 24%.

Crush represents “Criminal Reduction Utilising Statistical History” or predictive policing as police officers are guided by algorithms. Criminologists and data scientists at the University of Memphis compiled crime statistics from across the city over time and overlaid it with other statistics such as social housing maps, outside temperatures etc. They then instructed algorithms to search for correlations in the data to identify crime “hot spots” which led the police to flood the crime hot spot areas with targeted patrols.

According to the Guardian, Dr Ian Brown, the associate director of Oxford University’s Cyber Security Centre, raises concerns over the use of algorithms to aid policing, as seen in Memphis where Crush’s algorithms have reportedly linked some racial groups to particular crimes: “If you have a group that is disproportionately stopped by the police, such tactics could just magnify the perception they have of being targeted.”

Can this system work here? As the Home Secretary, Theresa May stated yesterday in Parliament:

Out of one million stop and search only 9% resulted in an arrest. So should Police Authorities use this or similar systems to target areas and predict crime or does it have the potential to create so-called crime “hot spots” with possible out of date data? There are then issues to take into account such as fairness and community confidence and the wasting of police time.

Theresa May July, 2nd 2013 http://www.parliamentlive.tv/Main/Player.aspx?meetingId=13391&player=smooth

Viktor Mayer-Schönberger, professor of internet governance and regulation at the Oxford Internet Institute, also warns against humans seeing causation when an algorithm identifies a correlation in vast swaths of data.

“This transformation presents an entirely new menace: penalties based on propensities, that are the possibility of using big-data predictions about people to judge and punish them even before they’ve acted. Doing this negates ideas of fairness, justice and free will.”

“In addition to privacy and propensity, there is a third danger. We risk falling victim to a dictatorship of data, whereby we fetishise the information, the output of our analyses, and end up misusing it. Handled responsibly, big data is a useful tool of rational decision-making. Wielded unwisely, it can become an instrument of the powerful, who may turn it into a source of repression, either by simply frustrating customers and employees or, worse, by harming citizens.”

http://www.guardian.co.uk/science/2013/jul/01/how-algorithms-rule-world-nsa