Home » crime and punishment (Page 3)

Category Archives: crime and punishment

Penitence versus Redemption in the Criminal Justice System: Unedited

I once entered a cell of a high-profile prisoner; his crime had been blazoned on every national newspaper and was serving the last few months of his sentence as an education orderly. He sat on his raised bed, his legs dangling over the menial storage where he had meticulously and precisely arranged his pairs of trainers and invited me to sit on the only chair in the cell. During our 20-minute conversation, he was pensive and reflective, looking down all the while, except for when he raised his head, adjusted his glasses, then looked me straight in the eye.

“Don’t count the days, but make every day count,” he said, his voice monotone and hushed. Yet behind him, I noticed a calendar marked with neatly drawn crosses. He was clearly counting down his days, paying his penitence until his eventual release from prison.

As an independent criminologist, I have met many who feel a deep-seated obligation to “pay back” continuously in some way to society or a higher power. Those who are caught and convicted for committing a crime experience punishment in some form or other, but when should that punishment end? Is it once a sentence has been served or longer?

Over the last 12 years, I have visited every category of prison in England and Wales and monitored a Category D prison for four years. In all that time, I have encountered hundreds of inmates, many struggling with the punishment, not only that of the sentence given by the courts, but the continual punishment they experience as they serve it, as well as after release and beyond.

The Ministry of Justice proudly states on their website that their responsibility is to ensure that sentences are served, and offenders are encouraged to turn their lives around and become law-abiding citizens. Apparently, the Ministry has a vision of delivering a world-class justice system that works for everyone in society, and one of four of their strategic priorities is having a prison and probation service that reforms offenders.

But I am not at all convinced by this hyperbole. In my opinion, we must stop the madness of believing that we can change people and their behaviour by banging them up in warehouse conditions with little to do, not enough to eat, and sanitation from a previous century.

Penitence

If true reform is supposed to be achieved through time served, then a former inmate emerging from prison with a clean slate would be ready to contribute fully to society. Yet beyond prison gates people who have served their time all too often live under a cloud of penitence, suppressing a sense of guilt for their deeds.

Many of the formerly incarcerated insist on a daily act of penitence, a good deed, even raising money for a worthy cause. For onlookers, such acts carry an air of respectability, but it is important to understand what is really happening on the inside because some of those who engage in them do so as a form of self-punishment. The punishing of self both physically and mentally.

They sense they must compensate.

Their account never fully paid.

Lifelong indebtedness.

And of course there are those who appear to genuflect to the Ministry of Justice and the Criminal Justice System; a sign of respect or an act of worship to those always in a superior position.

On the balance of probabilities, it is more likely than not that some penal reform organisations and some individuals with lived experience approach the Ministry of Justice with such reverence showing their cursory act of respect.

The same act of penitence or faux reverence ingrained into them whilst they served their custodial sentence.

For others penitence is an act devoid of meaning or performed without knowledge.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the definition of penitence is “the action of feeling or showing sorrow and regret for having done wrong, repentance, a public display of penitence.” In addition to the formal punishment they endure, many prisoners engage in penitence both physically and mentally during and after serving their time, which keeps them from moving forward with their lives and is damaging to their sanity.

According to a 2021 report by the Centre for Mental Health, (page 24) “former prisoners…had significantly greater current mental health problems across the full spectrum of mental health diagnosis than the general public, alongside greater suicide risk, typically multiple mental health problems including dual diagnosis, and also lower verbal IQ…and greater current social problems.”

In my work, I have found that some people who have broken the law want others to know that they are sorry, whilst at the same time feel the pressure to prove this to themselves. In such cases, their penitence becomes a public display for families, caseworkers, and those in authority.

Witnesses to this display of penitence often think these people are a good example of someone who has turned their life around, but often, these former prisoners find themselves stuck in the act of penitence. Rather than turning their lives around, they are trapped forever in their guilt. In these cases, the act of atoning becomes all-consuming, an insatiable appetite to heed the voices in their soul that tell them, “you must do more and more, it’s not enough, I’m hungry.”

Redemption

When I speak to those who are serving a whole-life tariff, I know that their debt to society can never be repaid: they are resigned to a lifelong burden of irredeemable indebtedness. But many of those who are released from prison remain incarcerated by their own guilt, feeling as if they must hide any hint of happiness they may find in life after prison so as not to be judged.

For example, in 2019, I interviewed Erwin James, author, Guardian columnist and convicted murderer, who had just come out with his third book, Redeemable: a Memoir of Darkness and Hope. When I asked him, “What makes you happy?” he replied: “In the public, if I am laughing, I feel awful because there are people grieving because of me. Even in jail, I was scared to laugh sometimes because it looked like I didn’t care about anything.”

Just like I saw with the prisoner sat on his bed, I have witnessed a cloud hanging over many, especially when redemption, or the act of repaying the value of something lost, relates to acceptance and society’s opinion of you.

There are of course prisoners who have the intellectual capacity to learn from their mistakes, have the emotional capacity to adapt to their situations and – not forgetting – the spiritual capacity, a dimension that can lead to a voyage of self-discovery. But by no means all.

Unfortunately, in the UK, paying back to society can either be the light at the end of the tunnel, or a tunnel with no light.

I believe we live in a punitive society in which the continual punishment of those who have offended is tacitly endorsed. In so doing, society inadvertently encourages the penitentiaries of this world to hold offenders in an ever-tightening grip.

Even a sentence served in the community—a sentencing option all too often shunned by magistrates—can carry an arduous stigma. In a public show of humiliation, the words “Community Payback” are garishly emblasoned on the offenders’ brightly-coloured outerwear, announcing their status as a wrongdoer to all who see them. Basically, this is society’s way of saying, “we want you to be sorry, we want you to show you are sorry and we will not let you forget it.”

Statements such as “the loss of liberty is the punishment” become fictitious, enabling punishment in its various form to continue throughout the sentence served and even after release.

Let us no longer have this traditional stance, rather should we try to embolden others to move on from their actions?

And can groundless nimbyism be finally assigned to history?

I am mindful that pain and grief still abounds, that some crimes will not be erased from our minds, and that crimes will stubbornly continue. But surely, the answer cannot be to condemn those who have done wrong to a lifetime without forgiveness.

To move forward as a society, we need to discourage the continual need to offer an apology, and instead accept when former prisoners have paid their dues and served their sentences. Only then will we move from a vicious cycle of unending penitence to a world in which reform and redemption is truly possible.

~

An edited version of this article was first published on 28 February 2022 by New Thinking.

~

A conversation with: Lady Val Corbett, passionate about prison reform, empowerment of women and kindness in business

Lady Val Corbett, a feisty woman, with determination to rival most, striking red hair and a penchant for wearing bright scarves, is one way of introducing my latest “A conversation with…” Having known Lady Val for 6 years, I have found her to be compassionate, hilarious, focused and above all, a friend.

Her career in journalism started in Cape Town but with moving to the UK it was impossible to continue without being a member of the National Union of Journalists. Eventually she worked for the Sunday Express as a weekend reporter; a Features Editor of a noteworthy Furnishing Magazine; Editor of a magazine Woman’s Chronicle for the Spar customers and grocers which then led to becoming the consumer columnist on The Sun. With the birth of her daughter, Polly, she invented herself several times!

“I wrote a column for Cosmopolitan and for national papers and magazines plus scriptwriter for BBC TV then became one of the founder directors of an independent TV production company which sold programmes for major broadcasters – highlight was a six-part BBC1 series called Living with the Enemy on teenagers as I was struggling with mine at the time. I was a volunteer at the Hoxton Apprentice, a training restaurant for long term unemployed and saw how people could change direction. After that I co-wrote six novels with two friends and in between was an MP’s wife and later the PA for Lord Corbett of Castle Vale, when I regularly gave notice or got fired.”

That’s quite a résumé.

Val had a chance encounter on her first day as a features writer, which led to 42 years of happy marriage.

“On my first day I was having second thoughts about a new dress I had bought. Going to the canteen for lunch I paused at the door and asked my colleague: “Does this dress make me look dumpy?” To which an amused male voice said: “Yes it does.” I looked up – my 5ft 2” to his 6ft 3” – and thought he was the rudest man I’d ever met. He called me Dumpy for ages.”

Her husband, Lord Corbett of Castle Vale, sadly died on 19th February 2012.

Did you personally have an interest in politics?

Not for party politics. I knew apartheid was wrong, unfair, and cruel. My first time voting as a British citizen was in Fulham when I put my cross next to Major Wilmot-Seale whom I believed was the Liberal candidate (party allegiances were not then on ballot papers). He was the National Front candidate and garnered 45 votes of which mine was one. Robin never let me forget this. Over the years he became my political mentor because he thought going into politics was because you wanted to change the world. And goodness how he tried!

When Robin decided a cause was just, he was not swayed from the path, do you feel you have taken on that mantle?

I could have chosen from several of his crusades – his Private Members Bill which became law, granting lifetime anonymity for rape victims in courts and media was one but he was also active in prison reform during his 34-year parliamentary career. Chairing the All-Party Penal Affairs Group for 10 years until his death made him realist how much there was to do in the criminal justice system.

He used to say: “Prison isn’t full of bad people; it’s full of people who’ve done bad things and most need a chance to change direction.”

Was it a mantle you were willing to take on?

Yes, when I heard a man say on TV “All men die but some men live on.” I wanted Robin’s legacy in prison reform to live on. Though a novice in prison reform I immersed myself in prison reform in 2013 and though I am still learning now feel I am no longer a novice.

What makes you laugh?

I laugh a lot particularly at short jokes and always tell one or two at my professional women’s network events.

What makes you cry?

Anything concerning cruelty to children.

Since 2016, I have been part of Lady Val’s Professional Women’s Network consisting of female entrepreneurs, senior women in business, the arts, government, investment, HR, and many more diverse professions.

It’s a forum for women in business looking to further their careers by focusing on leadership skills, self-confidence, and other key areas of personal development. Meeting five times per year for lunch, each event starts with an icebreaker “How can I help you and how can you help me”, a simple formula which encourages meaningful connections. This is followed by an inspirational speaker, a leader in their field sharing business knowledge and expertise.

The professional networking lunches are all about business and not entertainment, how do you reflect that in your choice of speakers?

I choose keynote speakers with care. Most speakers have been leaders in their field of business: marketing, fin tech, green economy, Lloyds of London, Abbey Road Studios etc. We had Michael Palin and Jon Snow, both prison reform campaigners, also Prue Leith and Jeffrey Archer. They attracted large audiences, but the Network is a business one, not an entertainment one… So, we are going back to basics, with speakers appealing to businesswomen. I’m happy that through the contacts not only have networkers gained business contacts but also friends.

We are all in this together and if women don’t help each other, who will?

What in your opinion are some of the barriers for women to advance in their professional lives?

The main barrier is a lack of confidence. The glass ceiling is there to be smashed but few women want to. This is changing though not fast enough for me! I count myself not as a feminist but as an equalist and am proud that the wearethecity.com network voted me one of their 50 Trailblazers in gender equality.

Face to face events are planned from April, are we all zoomed out after 2 years?

Zoom has become increasingly unpopular, and I hope we can go back to somewhere near our normal lives. I am worried that although the stats of Covid are decreasing, they are still worryingly high. On April 21st we are going back to Browns Courtrooms to restart our lunches with keynote speaker James Timpson who’ll be talking about kindness in business.

This network is not for ladies who lunch but ladies who work.

A donation comes from each booking going to our work on prison reform.

How did the Robin Corbett Award come about?

After a loved one dies, people gather around giving you sympathy and many cups of tea. A few weeks after the funeral they seem to think you will be able to manage but it is then that you are at your lowest. It was at this point that inspiration struck. As I mentioned before, the sentence I heard on TV: “All men die but some men live on.” was a eureka moment making me decide that I wanted Robin’s legacy to live on.

The Robin Corbett Award celebrates, supports, and rewards the best in prisoner re-integration programmes. Each year we donate funds to three charities, social enterprises or CICs whose mission is centred around giving returning citizens a chance to reintegrate back into society. The presentation is at the House of Lords.

The Robin Corbett Award for Prisoner Re-Integration was established by members of Lord Corbett’s family in conjunction with the Prison Reform Trust in 2013. It is now administered by The Corbett Foundation, a not-for-profit social enterprise.

What are the criteria to being a member of the Corbett Network?

The Corbett Network is a coalition of charities, social enterprises, community interest companies, non-profit organisations and businesses with a social mission who work with those in prison and after release. (Individuals are not eligible). These decision makers are dedicated to reducing re-offending by helping returning citizens find and keep a job. Some members offer mentoring, coaching, training or education.

How many members are there?

Currently there are 108 with four waiting to be introduced to their fellow members.

This network has expanded rapidly over the last few years, is this due to prison reform taking a greater platform?

Once the Robin Corbett Award was established, I kept on meeting people working in their own small pond, so to speak. I thought we could crusade better in a sea and invited them to join us. Since then, together we have created a powerful lobbying voice heard at the highest levels of government and recognized by those in the criminal justice sector as a force for change. I do sense that the media tend to focus on the problems.

Where do you see the Corbett Network positioned in the justice arena?

Peter Dawson, Director of the Prison Reform Trust told me that The Corbett Network is the only one of its kind in the UK. It sits alongside the Criminal Justice Alliance and Clinks which concentrate mainly on policing, courts, prisons, probation, and human rights. The Corbett Network are members of both these organisations.

What are your hopes for the future of this network?

To crusade effectively. To effect changes desperately needed in our prison system. To change public perception of people who have been inside – they are not sub- human. Since the Network started in 2017, we now have over 108 members, holding both face-to-face, virtual meetings, conferences and, crucially, encouraging greater collaboration across the work we collectively do. Together, we have created a powerful lobbying voice, heard at the highest levels of government, and recognised by those in the criminal justice sector as a force for change.

“Prisons should not be society’s revenge but a chance to change direction.” Robin Corbett

This interview was published to mark International Women’s Day 2022.

All photos courtesy of Lady Val Corbett. Used with permission.

Should inmates be given phones?

Offenders who maintain family ties are nearly 40% less likely to turn back to crime, according to the Ministry of Justice. With secure mobiles being rolled out in prisons we ask…

Should inmates be given phones?

This was a question posed to me back in November 2021 by Jenny Ackland, Senior Writer/Content Commissioner, Future for a “Real life debate” to be published in Woman’s Own January 10th 2022 edition.

Below is the complete article, my comments were cut down slightly, as there was a limited word count and reworked into the magazine style.

Communication is an essential element to all our lives, but when it comes to those incarcerated in our prisons, there is suddenly a blockage.

Why is communication limited?

It is no surprise that mobile phones can serve as a means of continuing criminal activity with the outside world, as a weapon of manipulation, a bargaining tool, a means of bullying or intimidation.

But what many forget is that prison removes an individual from society as they know it, with high brick walls and barbed wire separating them from loved ones, family, and friends.

There is a PIN phone system where prisoners can speak with a limited number of pre-approved and validated contacts, but these phones are on the landings, are shared by many, usually in demand at the same time and where confidentiality is non-existent. This is when friction can lead to disturbances, threats, and intimidation.

Some prisons (approx 66%) do have in-cell telephony, with prescribed numbers, monitored calls and with no in-coming calls.

Why do some have a problem with this?

We live in an age of technology, and even now phones are seen as rewarding those in prison.

If we believe that communication is a vital element in maintaining relationships, why is there such opposition for prisoners?

In HM Chief Inspector of prisons Annual report for 2020, 71% of women and 47% of men reported they had mental health issues.

Phones are used as a coping mechanism to the harsh regimes, can assist in reducing stress, allay anxiety and prevent depression.

Let’s not punish further those in prison, prison should be the loss of liberty.

Even within a prison environment parents want to be able to make an active contribution to their children’s lives. Limiting access to phones penalises children and in so doing punishes them for something they haven’t done. They are still parents.

Guest blog: Being visible: Phil O’Brien

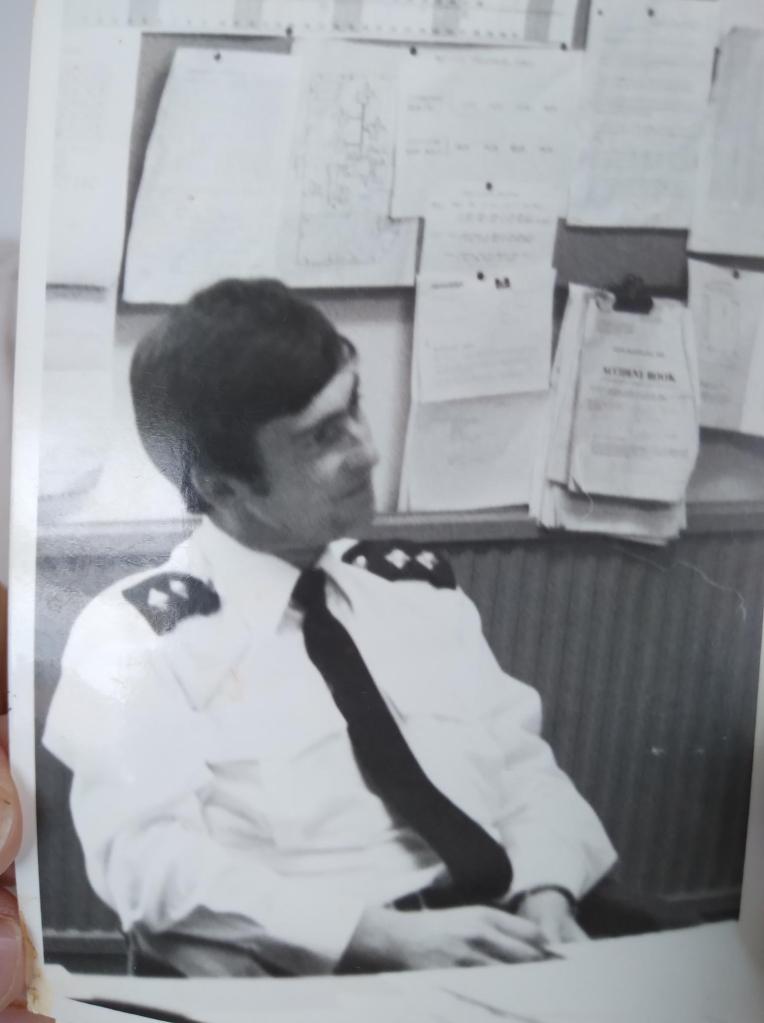

An interview with Phil O’Brien by John O’Brien

Phil O’Brien started his prison officer training in January 1970. His first posting, at HMDC Kirklevington, in April 1970. In a forty-year career, he also served at HMP Brixton, HMP Wakefield, HMYOI Castington, HMP Full Sutton, HMRC Low Newton and HMP Frankland. He moved through the ranks and finished his public sector career as Head of Operations at Frankland. In 2006, he moved into the private sector, where he worked for two years at HMP Forest Bank before taking up consultancy roles at Harmondsworth IRC, HMP Addiewell and HMP Bronzefield, where he carried out investigations and advised on training issues. Phil retired in 2011. In September 2018, he published Can I Have a Word, Boss?, a memoir of his time in the prison service.

John O’Brien holds a doctorate in English literature from the University of Leeds, where he specialised in autobiography studies.

You deal in the first two chapters of the book with training. How do you reflect upon your training now, and how do you feel it prepared you for a career in the service?

I believe that the training I received set me up for any success I might have had. I never forgot the basics I was taught on that initial course. On one level, we’re talking about practical things like conducting searches, monitoring visits, keeping keys out of the sight of prisoners. On another level, we’re talking about the development of more subtle skills like observing patterns of behaviour and developing an intimate knowledge of the prisoners in your charge, that is, getting to know them so well that you can predict what they are going to do before they do it. Put simply, we were taught how best to protect the public, which includes both prisoners and staff. Those basics were a constant for me.

Tell me about the importance of the provision of education and training for prisoners. Your book seems to suggest that Low Newton was particularly successful in this regard.

Many prisoners lack basic skills in reading, writing and arithmetic. For anyone leaving the prison system, reading and writing are crucial in terms of functioning effectively in society, even if it’s only in order to access the benefits available on release.

At Low Newton, a largely juvenile population, the education side of the regime was championed by two governing governors, Mitch Egan and Mike Kirby. In addition, we had a well-resourced and extremely committed set of teachers. I was Head of Inmate Activities at Low Newton and therefore had direct responsibility for education.

The importance of education and training is twofold:

Firstly, it gives people skills and better fits them for release.

Secondly, a regime that fully engages prisoners leaves less time for the nonsense often associated with jails: bullying, drug-dealing, escaping.

To what extent do you believe that the requirements of security, control and justice can be kept in balance?

Security, control, and justice are crucial to the health of any prison. If you keep these factors in balance, afford them equal attention and respect, you can’t be accused of bias one way or the other.

Security refers to your duty to have measures in place that prevent escapes – your duty to protect the public.

Control refers to your duty to create and maintain a safe environment for all.

Justice is about treating people with respect and providing them with the opportunities to address their offending behaviour. You can keep them in balance. It’s one of the fundamentals of the job. But you have to maintain an objective and informed view of how these factors interact and overlap. It comes with experience.

What changed most about the prison service in your time?

One of the major changes was Fresh Start in 1987/88, which got rid of overtime and the Chief Officer rank. Fresh Start made prison governors more budget aware and responsible. It was implemented more effectively at some places than others, so it wasn’t without its wrinkles.

Another was the Woolf report, which looked at the causes of the Strangeways riot. The Woolf report concentrated on refurbishment, decent living and working conditions, and full regimes for prisoners with all activities starting and ending on time. It also sought to enlarge the Cat D estate, which would allow prisoners to work in outside industry prior to release. Unfortunately, the latter hasn’t yet come to pass sufficiently. It’s an opportunity missed.

What about in terms of security?

When drugs replaced snout and hooch as currency in the 1980s, my security priorities changed in order to meet the new threat. I had to develop ways of disrupting drug networks, both inside and outside prison, and to find ways to mitigate targeted subversion of staff by drug gangs.

In my later years, in the high security estate, there was a real fear and expectation of organised criminals breaking into jails to affect someone’s escape, so we had to organise anti-helicopter defences.

The twenty-first century also brought a changed, and probably increased, threat of terrorism, which itself introduced new security challenges.

You worked in prisons of different categories. What differences and similarities did you find in terms of management in these different environments?

Right from becoming a senior officer, a first line manager at Wakefield, I adopted a modus operandi I never changed. I called it ‘managing by walking about’. It was about talking and listening, making sure I was there for staff when things got difficult. It’s crucial for a manager to be visible to prisoners and staff on a daily basis. It shows intent and respect.

I distinctly remember Phil Copple, when he was governor at Frankland, saying one day: “How do you find time to get around your areas of responsibility every day when other managers seem tied to their chairs?” I found that if I talked to all the staff, I was responsible for every day, it would prevent problems coming to my office later when I might be pushed for time. Really, it was a means of saving time.

The job is the same wherever you are. Whichever category of prison you are working in, you must get the basics right, be fair and face the task head on.

The concept of intelligence features prominently in the book. Can you talk a bit about intelligence, both in terms of security and management?

Successful intelligence has always depended on the collection of information.

The four stages in the intelligence cycle are: collation, analysis, dissemination and action. If you talk to people in the right way, they respond. I discovered this as soon as I joined the service, and it was particularly noticeable at Brixton.

Prisoners expect to be treated fairly, to get what they’re entitled to and to be included in the conversation. When this happens, they have a vested interest in keeping the peace. It’s easy to forget that prisoners are also members of the community, and they have the same problems as everyone else. That is, thinking about kids, schools, marriages, finances. Many are loyal and conservative. The majority don’t like seeing other people being treated unfairly, and this includes prisoner on prisoner interaction, bullying etc. If you tap into this facet of their character, they’ll often help you right the wrongs. That was my experience.

Intelligence used properly can be a lifesaver.

You refer to Kirklevington as an example of how prisons should work. What was so positive about their regime at the time?

It had vision and purpose and it delivered.

It was one of the few jails where I worked that consistently delivered what it was contracted to deliver. Every prisoner was given paid work opportunities prior to release, ensuring he could compete on equal terms when he got out. The regime had in place effective monitoring, robust assessments of risk, regular testing for substance abuse and sentence-planning meetings that included input from family and home probation officers.

Once passed out to work, each prisoner completed a period of unpaid work for the benefit of the local community – painting, decorating, gardening etc.

There was excellent communication.

The system just worked.

The right processes were in place.

To what extent do you feel you were good at your job because you understood the prisoners? That you were, in some way, the same?

I come from Ripleyville, in Bradford, a slum cleared in the 1950s. Though the majority of people were honest and hardworking, the area had its minority of ne’er-do-wells. I never pretended that I was any better than anyone else coming from this background.

Whilst a prisoner officer under training at Leeds, I came across a prisoner I’d known from childhood on my first day. When I went to Brixton, a prisoner from Bradford came up to me and said he recognised me and introduced himself. I’d only been there a couple of weeks. I don’t know if it was because of my background, but I took an interest in individual prisoners, trying to understand what made them tick, as soon as I joined the job.

I found that if I was fair and communicated with them, the vast majority would come half way and meet me on those terms. Obviously, my working in so many different kinds of establishments undoubtedly helped. It gave me a wide experience of different regimes and how prisoners react in those regimes.

How important was humour in the job? And, therefore, in the book?

Humour is crucial. Often black humour. If you note, a number of my ex-colleagues who have reviewed the book mention the importance of humour. It helps calm situations. Both staff and prisoners appreciate it. It can help normalise situations – potentially tense situations. Of course, if you use it, you’ve got to be able to take it, too.

What are the challenges, as you see them, for graduate management staff in prisons?

Credibility, possibly, at least at the beginning of their career. This was definitely a feature of my earlier years, where those in the junior governor ranks were seen as nobodies. The junior governors were usually attached to a wing with a PO, and the staff tended to look towards the PO for guidance. The department took steps to address this with the introduction of the accelerated promotion scheme, which saw graduate entrants spending time on the landing in junior uniform ranks before being fast-tracked to PO. They would be really tested in that rank.

There will always be criticism of management by uniform staff – it goes with the territory. A small minority of graduate staff failed to make sufficient progress at this stage and remained in the uniform ranks. This tended to cement the system’s credibility in the eyes of uniform staff.

Were there any other differences between graduate governors and governors who had come through the ranks?

The accelerated promotion grades tended to have a clearer career path and were closely mentored by a governor grade at HQ and by governing governors at their home establishments and had regular training. However, I lost count of the number of phone calls I received from people who were struggling with being newly promoted from the ranks to the governor grades. They often felt that they hadn’t been properly trained for their new role, particularly in relation to paperwork, which is a staple of governor grade jobs.

From the point of view of the early 21stC, what were the main differences between prisons in the public and private sectors?

There’s little difference now between public and private sector prisons. Initially, the public sector had a massive advantage in terms of the experience of staff across the ranks. Now, retention of staff seems to be a problem in both sectors. The conditions of service were better in the public sector in my time, but this advantage has been eroded. Wages are similar, retirement age is similar. The retirement age has risen substantially since I finished.

In my experience, private sector managers were better at managing budgets. As regards staff, basic grade staff in both sectors were equally keen and willing to learn. All that staff in either sector really needed was purpose, a coherent vision and support.

A couple of times towards the end of your book, you hint at the idea that your time might have passed. Does your approach belong to a particular historical moment?

I felt that all careers have to come to an end at some point and I could see that increasing administrative control would deprive my work of some of its pleasures. It was time to go before bitterness set in. Having said that, when I came back, I still found that the same old-fashioned skills were needed to deal with what I had been contracted to do. So, maybe I was a bit premature.

My approaches and methods were developed historically, over the entire period of my forty-year career. Everywhere I went, I tried to refine the basics that I had learned on that initial training course.

Thank you to John O’Brien for enabling Phil to share his experiences.

~

A conversation with: Barry Thacker, Deputy Chief of Police, The Falklands, South Georgia, and South Sandwich Islands

Introduction

It’s May 1982, holidaying in Somerset, where new friendships in the making were overshadowed by the Falklands War. Faith, Pam, Mark, Sally, Denise and Barry …

Each day we bought and read together the Times newspaper, the broadsheet format detailing the horrors of war, the loss, the gains, the heartbreak of lives sacrificed, the images of destruction. The Falklands War will forever be etched in my memory. We all kept in touch for a few years, but then we all went our separate ways.

Fast forward almost 40 years.

I’m sat at my computer engaging in a zoom conversation with Barry Thacker, Deputy Chief of Police of the Falkland Islands. Reminiscing about that holiday back in 1982. Barry was 18, I was 17 with our lives ahead of us. Never knowing that all these years later our paths would cross again.

Remarkable.

Tell me a little about your family background.

I am from a small mining village on the Derbyshire/Nottinghamshire border. My dad, a miner all his life, died prematurely at 69 with pneumoconiosis. My mum is still going well at 90. I am the youngest of 4 and had a comprehensive education. Life was a little tough during 1984 and the UK miners’ strike but as a family we got through it. My wages kept us and some friends afloat.

When you left school what was your first job?

Fruit and veg assistant at a local wholesaler. It was where I met Ivan Bamford, my supervisor, who was a special constable. After a few weeks, an opportunity arose on a government YTS (Youth Training Scheme) at the police station, I felt it would give me experience into a career I really wanted to pursue. It wasn’t long into the YTS that I was taken on full time as an admin clerk and when I hit 18 there was no recruitment so I joined the Derbyshire Special Constabulary working for Ivan again.

Why were you unsuccessful in joining the Police Cadets, did you ever think of giving up and choosing a different path?

I know it is a cliché, but I always wanted to be a cop after receiving a police pedal car for Christmas one year. When I left school there were still paid police cadets, so when I was in the 5th year (Y11 now) as Nottinghamshire police were recruiting cadets, I applied and was successful with the entrance exam. However, I wasn’t successful in my ‘O’ level (GCSE) English so was told to wait until I was 18 and try straight for the regular police.

You eventually started working for the police by finding another route. Do you think that part of your character is to not give up but find alternatives to situations?

I am a big believer in things happening for a reason and although not knowing at the time as you reflect on your life things become evident. Whatever setbacks we have in life I always try to see the good and by entering the police at the bottom, so to speak, I can appreciate the frustrations of all ranks. It is that emotional intelligence which I like to think has got me to where I am today looking after the policing for 3 overseas territories, The Falklands, South Georgia, and South Sandwich Islands.

You were presented with a silver baton, explain what that was for.

I attended my initial 14-week training at Ryton on Dunsmore police college. As it had taken me many setbacks to get where I wanted to be I was determined to prove myself, I focused my efforts and became class leader and never scored less than 90% on my weekly and course exams. At pass out I was awarded the Commandant’s baton for top student on the course.

My initial posting as a regular PC was the East of Derby City, a multicultural deprived area of the city.

Being brought up in a small Derbyshire town was a far cry from working in Derby. What were some of the challenges you faced?

The innocence and trust I was used to in a small village was a far cry from inner city Derby. I wasn’t averse to deprivation and need but the support of a village wasn’t always there in an often faceless city.

It was my first time away from home, living in a small council owned flat. Initially I had litter, food and other unmentionables posted through my letter box, everyone knew it was a police flat. The anti-social behaviour towards me was short lived, I became established in the estate, I think like life in general it’s very much how you interact and deal with people that gets you results; yes, I was a cop, but I was their cop and they often sought my advice ‘off the record’ but with the understanding I was still a cop and on occasions had to take action on what they told/asked me.

Over your 32-year career with Derbyshire Constabulary, you received 8 commendations for your work. Can you expand on a few?

As a young cop I was sent to a boy/girl friend splitting up and when I arrived the young man had poured petrol over the girl’s car and was going to set it alight. Following a struggle which resulted in us both getting covered in petrol from the can he had used I had, for the first and only time in my career, struck someone with my truncheon – proportionate force – to make him release the lighter he was trying to use to set us and the car alight.

A businessman was kidnapped as he left his factory in Leicester and driven to Birmingham with a demand for £1.5m from his family for his safe release. I was appointed negotiator coordinator for the 5 counties of the East Midlands and had to staff this incident through mutual aid between all the forces, as well as maintain trained negotiators to respond to others calls for negotiator input. At one stage I was managing the kidnap in Leicester and 2 suicide interventions in Nottinghamshire and Northampton. This was I think one of the most stressful yet rewarding parts of my career, saving all lives. The 3 offenders from the kidnap received a total of 90 years imprisonment.

You received a Certificate in Counter Terrorism from St Andrews in 2007, what led you to study?

As part of my role as County Partnership Inspector, part of my portfolio was that of the prevent part of the government’s Contest anti-terrorism agenda, the other parts being prepare, pursue, and protect. I had to coordinate police and partner agency resources to prevent the threat of terrorism within the county. So, to increase my knowledge and support my role as a Home Office terrorism trainer, I did the course.

Serving 32 years with the Derbyshire Constabulary is quite a commitment

Yes, I had some good times with amazing people and some truly inspiring leaders. The police service isn’t just a job but a calling, a family atmosphere of mutual respect and willingness to help and support each other; there are some terrible incidents officers witness. I’ve had numerous ones. For example, I’ve been handed a severed head in a carrier bag, you need that support to get you through. There is a lot of media negativity and society kick back to the police, but we are the ones who are there to always give that help and support to others putting our own feelings aside until the job is done.

You took retirement around your 50th birthday. Did you plan it that way?

That is the way the police pension works; you pay in 14% of you pay throughout your 30-year career to retire at this age. I did the extra 2 years to establish a project I started of a multi-agency web-based information sharing system.

From having active roles in the community for so long how did it feel for that chapter in your life to close?

It was difficult and takes time to get over the fact you have no powers, handing over my warrant card after so long was a big thing. But the constabulary try to prepare you and, as I have said previously, the support of family and network of friends gets you through it.

How important has it been for you during your police career to be authentic?

I owe a lot to my humble beginnings and how my parents raised me and the standards and morals they instilled in me. My faith has been tested at times but I have always come through and grown through life lessons; at times it was the only thing keeping me going.

Retirement did not last long as you “missed the buzz of the Police” So, you applied for a very unusual position, far away from friends and family and initially became Senior Constable with the Royal Falklands Police on a 2-year placement. So, what changed as you are still there?

I saw the advert on LinkedIn and fancied an adventure and the experience of a Southern Hemisphere life. I also thought of the experience I could bring to the role and so an enriched service to the community. I thought what an opportunity to forget about budgets, staffing, politics, policies, etc and returned to the role of Constable where I started many years ago.

The Falkland Islands is a truly awesome location. The scenery, wildlife, sunrises and sunsets, and amazing stars at night together with a lovely community. So a 2-year contract was signed. After just 9 months I was promoted to deputy Chief of Police and a further 2 year contract was signed, so I’m currently in my 3rd year here finishing at the end of 2022. Then let’s see what the next chapter of my life has in store.

I have had the privilege of meeting the Chiefs of the other Overseas Territories and I feel blessed to be looking after the ones I do, but who knows? Maybe somewhere a tad warmer next?

How different is policing on the Falkland Islands?

I have policed deprived areas, I’ve policed affluent areas, and everywhere in between. Each area is unique and there is good everywhere, sometimes a tad more difficult to find but it will always be there. The Falkland Islands has a population of around 3,000 (by comparison Derbyshire Constabulary had more staff working for them) is very much a community that people reminisce of; the community is great and most people know each other.

There is very little aquisitive crime and people are honest and genuinely care about their lifestyle, each other, and the environment they share with the wildlife. There is also a military camp and I have developed an exceptional working relationship with them, something I couldn’t have done in the UK and the experiences I would never have been exposed to in the UK.

Being personal friends with His Excellency The Governor and his wife are, again, the sort of opportunities I couldn’t even dream about in the UK. However, with the island being so law abiding, any breaches of the law are magnified in ways which they never would be in the UK.

I am very much aware of the privileged position I hold and the additional restrictions that puts on my social life in addition to those of a regular police officer.

You once wrote “I am passionate about community work especially giving a voice to the most vulnerable and believe in the encouragement and mentoring of young people helping them to achieve their full potential” how are you able to put this into practice where you are now?

I continue to believe in community which I hope I have demonstrated throughout this conversation. During my time as Senior Constable here I took on the role of school liaison. I have been able to be there for these young people, helping them continue their studies in the UK and have enjoyed watching some of them grow into independent adults.

If I can help guide and break down any barriers between young people and the police then that must be a good job – as with the rest of the community – to be appreciative of their lives, to take an interest but be firm and fair; enforcing the law without fear or favour, malice, or ill will.

To summarise I have had a fulfilled career as a UK officer and still doing the job I love helping and supporting people in need.

We all carry hang ups, problems and insecurities and not everyone knows how to deal with their own issues and interactions with others. Someone once told me people will forget what you say to them but not how you make them feel.

Compassion and understanding go a long way to endear us to each other.

~

All photographs used with the kind permission of Barry Thacker

~

‘The Grass Arena’ by John Healy

‘The Grass Arena’ by John Healy is a book centred round a world I thankfully have never ventured into – either by choice or circumstance. Drink, drugs, vagrancy, death, prostitution and money – the somewhat graphic portrayal of a life I can only describe as ‘brutal’.

A daily struggle for life itself, for the breath to breathe and the sustenance to give strength is a battle many start but then give up, as hurdles become visible, barriers are built and prejudice is rife. Drink becomes an obsession. I am sure we have all at some point tried to look through the window of others’ lives. We analyse their behaviour; we penalise whilst categorising them, we pity them. Not forgetting we compare their misfortune with our own accomplishments.

We read about them. Some use it as research to further their own life chances whilst disregarding the people involved. Some may find it entertaining; others as a measure of how they personally are doing, or how far they have failed. For myself, when reading about others there is an element of intrigue of course, but it’s more than that. I do not like small talk, its uncomfortable. I want facts and meaningful conversations. That is true communication.

This book communicates.

I frequently read about people’s journeys in life.

We all have a story to tell and I am eager to listen.

I have met many authors with fascinating quotes and anecdotes and maybe one day I will have the opportunity of meeting John. It was hard to put down this autobiography, an often harrowing account mirrored by the lines on my forehead, my furrowed brow. It is intense, it is absorbing yet thought provoking in a greater sense than most books on my shelves.

“Life was becoming more complicated. I was back in the old routine: stealing, drinking, fighting, my probation order, car insurance, detectives. I was pulling so many strokes for drink that I could not remember what I was doing…”

The stories of Fred, Dipper, Spikey and more carry merit, lives entwined with a common desire in life. Their struggles, contentions, crusades, rivalry and exploitations all add to the chart laid out in front of us.

“We look at people with only one thought. How can we get the price of a drink out of them? Looking, always looking, even when there is nothing to observe”.

An obsession leading to a lifestyle and a painful path trodden – alcohol picking you off one by one becomes a dangerous liaison. Yet seeing others fall is no way to interrupt the cycle, there is no end in sight, its continuous. I tried not to interpret my initial thoughts, the “if only”, “but” or even “what if” can become a distraction.

I just read. The shady doorways, the open green spaces, the derelict houses and the public houses all feed John’s obsession. Recovery from excess is quick and the thought of drink is always on his mind and he will do anything to take the constant battle, the weight on his shoulders and the voice in his ear, away.

This book is about a fight for survival, the many characters described within it are people trying to get through trauma, abuse and hopelessness. Many do not make it through.

Prison, I would not wish on anyone, I have visited enough to know they are not holiday camps, never have been and never will be. They are dangerous places. Here in ‘The Grass Arena’ they imitate the chaotic world that John is in. Familiar faces, familiar stories, and familiar issues to deal with.

Is it possible to escape from the grip of an obsession – even in prison? I read with impatience, asking that question many times.

Can John break free?

Does he want to break free?

Slowly but surely his obsession is substituted, by a game of chess. Yes chess, a game often associated with money, with brilliant minds; not a wino living each day for the dangerous toxic thrill of a drink.

A good book impacts you, challenges you, and this book is no exception, but it does leave the reader wanting more.

As I wrote earlier, it is a window into many lives and now the onus is on the reader to decide what to do next…

first published, Insidetime November 2020

A conversation with: Erwin James

Busy train

Busy tube

Busy London streets

Police everywhere

I made my way out of the crowds towards my destination: The National Portrait Gallery, London.

Although this will be a time to indulge my love of Art, I’m actually here to interview rather than be an interviewee.

I arrived early and found a quiet(ish) corner of the café to collect my thoughts, helped enormously by the Earl Grey tea and slice of orange and polenta cake.

Two days previously I attended the Koestler Art exhibition on the South Bank entitled “Another Me”

I prefer to visit alone; I don’t want other people’s initial reflections to become mine. For me it’s not just the pieces of art that can stop me in my tracks but the titles of the pieces. This year I discovered “Stand Alone”, “Consequences”, “Innocent Man” and “Woo Are You Looking at?”.

From matchsticks to J-cloths, from socks to gold leaf such variety of materials, such ingenuity.

But the question that stayed in my mind was:

“Are these exhibits examples of escapism or expressionism?”

I made my way up to the large information desk at the National Portrait Gallery and sat patiently awaiting my guest.

Ten minutes later, he arrived looking rather bemused at my choice of venue to interview him.

Erwin James followed me up a flight of stairs where we slowly wandered around looking at portraits of people, from HM The Queen to Zandra Rhodes and every conceivable individual in between.

Trying to get my bearings, we turned a corner and entered the Statesmen’s Gallery, lined on each side by a series of white marble busts on projecting plinths in between painted portraits. It looked outstanding.

At the far end hung a portrait painting of Dame Christabel Pankhurst by Ethel Wright (oil on canvas, exhibited 1909), militant Suffragette, persuasive speaker and effective strategist. Erwin and I stood and pondered.

In one of the rooms off this gallery we found a bench, sat down and started to talk. Straight ahead was a significant portrait, covering a large part of the wall, entitled:

The Mission of Mercy: Florence Nightingale receiving the Wounded at Scutari

The Mission of Mercy: Florence Nightingale receiving the Wounded at Scutari by Jerry Barrett. Oil on canvas. 1857

Faith Spear: When you look at that picture what does it tell you?

Erwin James: There are people who care about people that others don’t care about. This lady cared for the wounded she didn’t care about the war, she cared about people.

FS: How does it make you feel when you see that?

EJ: My experience of prison was that occasionally, more than occasionally there are people who care about people, about the wounded people in our prisons who need assistance, it’s a challenge for any community or society to think that we should care or help those that have hurt us. But she cared about everybody.

FS: Do paintings like that inspire you?

EJ: I found paintings in prison. I did an Arts degree and I was given this folder of great art; I had never had access to art or that sort of thing, ever in my life until I went to prison. I found art through the Open University.

I have never seen this painting before if I’m honest, but it tells us, “this lady, she doesn’t care who you are. She just wants to heal you.” The Onlookers: What are they thinking, should we help this person? There’s hesitance, others are standing away, observing. But you can’t hesitate or observe when people need help. My feeling about our attitudes to prisoners is that’s it’s a challenge to help people who’ve hurt us but if we don’t help them, they are going to hurt more people. When I look at that painting, I promise you some are taking advantage of the crowd.

FS: That’s interesting “taking advantage of the crowd”

EJ: We do that in our society now, longer prison sentences…we deserve a prison system that hates the crime, perhaps hates the criminal but for Christ sake give the prisoner a chance. That’s my philosophy really.

We slowly moved from room to room admiring and yet questioning the art we saw. Both of us were struck by a painting of Henrietta Maria (1635) and our hidden thoughts became open dialogue

EJ: Look how attractive we are, look how wealthy we are, look how amazing we are

FS: Always trying to prove something

EJ: Always

FS: Is that because people can’t accept who they are?

EJ: People seem to want to portray an image that is more than what they are, that is exactly what these people did

FS: It’s not just status is it?

EJ: Status, its look at me, look at us, all the poverty in the country when she was painted.

The poor people, we always looked up to the people doing well, we always aspire to be like them

FS: Always looking down on those that are not doing so well?

EJ: I don’t know why because we are all trying to get up that ladder

FS: Do you think we fall into the trap that we don’t actually accept people for who they are?

EJ: Well we are not sure who they are, all we know is we think we know who we are we want to be better versions of ourselves come what may

There are many self-portraits in the National Portrait Gallery, some more obvious than others.

FS: With a self-portrait you are not necessarily portraying the real you

EJ: No, you are portraying what you want the world to know about you. As a writer I am the same, I’m exactly the same, I want the world to know me through words because the world sort of knew me through the courts through prison through prosecution

FS: So, do you think you were trying to re-invent yourself

EJ: Yes

FS: But then that is saying previously that wasn’t the true you

EJ: Yes, that wasn’t the true me

FS: Do you think that this is the true you now, what you are doing now?

EJ: Yes, before I became who I think I am, I’m not perfect by any means, but I am my own person and I think lots of people go through life thinking, well is this me? I’m born into this way of living but gradually you think did I decide this. Other people decide our lives and what prison gave me was the freedom to choose my own, if that makes any sense. But even though I am a million miles away from perfect, I am a real person

They all portray dominance over everyone else. The whole purpose of art in these ages was to say look at us, we dominate you – and then the dominated looked up and said, “we are so pleased to be dominated by you”, we didn’t know then that any of us could be dominate and dominated we didn’t realise then before mass education, we didn’t understand that we can all be people with education with skills and abilities

We walked up to level 2, not knowing what to look at first. We entered a small room.

FS: Do you see that painting over there of John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester, with his books showing he is an educated man, well in fact, a poet?

EJ: Books for the educated people? No. books are for everyone, to me Faith, books are a great leveller. If you can read, you can be a King.

By this time, I needed to sit down; juggling bag, jacket, notebook, pen and phone was getting problematic. I found a wooden bench in one of the corridors and with phone at the ready I continued my questions as we sat down.

FS: One thing I am always amazed at in an art gallery is that everything is categorised, often by year, era or by event. Everything is numbered. And there is a lot of security. When you come into an art gallery you are watched by cameras everywhere.

Everything is numbered, everything is categorised exactly the same as it is in a prison.

How did it feel to be categorised and given a number?

EJ: That is a really good question.

Well I was categorised; I was a Cat A prisoner for 5 or 6 years. The system categorises you and gives you a number. I hated my prison number. I was in Devon driving down a lane and I saw a signpost for the B73…, arghhhhhh! That’s my prison number!

It was awful, I had forgotten it, forgotten it purposely. When you are categorised and given a number you become labelled, you’re not human you’re a prisoner. But thank god there are some amazing people that work in prisons who want you to be human. For various reasons you end up there, they work there, and they are there to help you to become like them. Thank god for that. Without those people I would never be here I would never have made it. Teachers, psychologists, probation officers some prison officers…

FS: But when people are reduced to a number do you think that is degrading?

EJ: Well I think the danger Faith, you are asking me something quite profound here, because the danger when we do that, we detach people psychologically from our community. Now prison is detaching. You did harm, you caused pain, grief etc, but what we do with that in our prison system is that we detach further psychologically so the people in prison psychologically don’t feel part of society. Don’t feel part of the community, there’s no sense of wanting to come back.

I want to do some good when I come back, but mostly we don’t want them back. But actually, there’s so many people that do come back do good but it’s the physiologically detachment that presents danger from the released prisoner.

As Erwin is a writer, I wanted to probe a little more into different aspects of his life.

FS: For someone who is setting out on a journey as a writer what advice would you give?

EJ: Well what I would say is first and foremost is tell your truth. But first, you have got to find your truth because if you don’t know your truth you will never be able to share that truth. So, there are a couple of things: have discipline, have courage because when you put your truth out there you are going to get people who hate you and your truth. You need to have courage and be bold, but as long as you know your truth you will have a significant number of people who will accept that. Whatever the obstacles whatever the challenges you just keep going.

I decided to probe a little deeper too.

FS: What makes you laugh?

EJ: You will be amazed how many people in prison laugh, it’s a funny thing in jail you laugh at the most banal things.

FS: But what makes you laugh now?

EJ: My great granddaughter she makes me laugh. “Grandad, grandad look at the chickens” she chases chickens and I run after her and I’m laughing like hell and then she catches a chicken. Then she chases the ducks.

I do laugh but I am a very serious thinker, but I laugh when she laughs, its infectious. I feel safe to laugh with my great granddaughter.

FS: Is that because you are not being judged?

EJ: In the public if I am laughing, I feel awful because there are people grieving because of me. Even in jail I was scared to laugh sometimes because it looked like I didn’t care about anything.

FS: What makes you cry, do you cry?

EJ: I cried a long time ago in prison when I came to terms with what I had done with the effects on victims’ families of my crimes. I didn’t cry before that.

What makes me cry now? A good drama where there’s an amazing writer who brings the human condition into our living rooms and shows us how weak, strong, dominant, how we are as humans.

That makes me cry.

My final question was about what others say.

FS: What is one of the most memorable statements about yourself?

EJ: The best thing that’s been said of me, that I am really proud of, I do school talks. I was in a school in Southampton a few years ago, the Headmaster said afterwards:

“It was one of the best talks we have had all year and, for some, will be an abiding memory of school.”

It was time to switch my recorder off, I took in a last view of this amazing gallery and headed outside for some air. After a refreshing drink we said goodbye and I headed for the tube.

What an interesting conversation.

Erwin James is editor-in-chief of ‘Inside Time’, the national newspaper for people in prison and the author of ‘Redeemable: A Memoir of Darkness and Hope’.

Photos: Copyright © FM Spear. All rights reserved.

~

HMP Berwyn: Does it raise more questions than it answers? Part 2

The Wales Governance Centre, a research centre and part of Cardiff University’s School of Law and Politics undertakes innovative research into all aspects of the law, politics, government and political economy of Wales.

This week they released a report: Sentencing and Imprisonment in Wales 2018 Factfile by Dr Robert Jones

Before looking at this report, lets put things in context by referring to the first unannounced inspection by HMIP of HMP Berwyn in March 2019. Here it is reported that “impressive” support procedures are in place for new arrivals. Positive note. However, use of force was considerably higher than at similar prisons and 1 in 4 prisoners (23%) told HMIP that they felt unsafe. Alarm bells?

Below are the four tests when inspecting a prison, Safety, Respect, Purposeful activity and Rehabilitation and release planning. Not the best outcome for the first inspection.

Safety: Outcomes for prisoners were not sufficiently good against this healthy prison test.

Respect: Outcomes for prisoners were reasonably good against this healthy prison test.

Purposeful activity: Outcomes for prisoners were not sufficiently good against this healthy prison test.

Rehabilitation and release planning: Outcomes for prisoners were not sufficiently good against this healthy prison test.

HMP Berwyn prison has only been open just over 2 years, hasn’t reached full capacity and has its 3rd governing Governor.

Now let’s look at some of the facts revealed that are not easy reading

The number of self-harm incidents

2017 = 231

2018 = 542

Self-harm incidents rose by 135% in 2018

Rate of self-harm: (48 per 100 prisoners)

This is what the Government website states:

“Self-harm may occur at any stage of custody, when prisoners are trying to deal with difficult and complex emotions. This could be to punish themselves, express their distress or relieve unbearable tension or aggression. Sometimes the reason is a mixture of these. Self-harm can also be a cry for help, and should never be ignored or trivialised” https://www.gov.uk/guidance/suicide-self-harm-prevention-in-prison

This is what the HMIP report states:

“The strategic management of suicide and self harm required improvement. Strategic meetings were poorly attended and too little was done to analyse, understand and take action to address the causes of self-harm. Most of the at-risk prisoners on assessment, care in custody and teamwork (ACCT) case management did not feel sufficiently cared for. ACCT documents required improvement, and initial assessments and care plans were weak”

Yet below are more uncomfortable facts showing that this prison is not just dangerous for prisoners but for staff too. Nothing to celebrate here.

The number of prisoner-on-prisoner assaults rose by 338% in 2018

Rate of prisoner-on-prisoner assaults: (20 per 100 prisoners)

The number of assaults on staff at HMP Berwyn increased by 405% in 2018

Rate of recorded assaults on staff (18 per 100 prisoners)

You would think that a new prison would have a security department second to none, with little chance of items being brought in. Yet these figures show that weapons, drugs, alcohol and tobacco are increasingly being found. Some may say hats off to the staff for finding these items, but really there’s still no cause for celebration…

The number of incidents where weapons were found in prison, years ending

March 2017 = 1

March 2018 =25

March 2019 Berwyn = 138

The rate of weapon finds (11 per 100 prisoners) year ending March 2019

This was the highest rate per prisoners in all prisons in Wales, astonishing. Serious problems with security.

The number of drug finds at HMP Berwyn increased by 328% in the year ending March 2019 (prison population increased by 67% during this period)

The rate of drug finds (16 per 100 prisoners)

Where are the robust measures to stop drugs coming into the prison?

The number of incidents where alcohol was found in HMP Berwyn years ending March

2017 = 0

2018 = 21

2019 = 146

Alcohol finds at HMP Berwyn rose by 595% (prison population increased by 67% during this period)

Rate of alcohol finds (12 per 100 prisoners) year ending March 2019.

Yet again the highest rate of alcohol finds in all the prisons in Wales

The number of incidents where tobacco was found in HMP Berwyn years ending March

2018 = 20

2019 = 61

Rate of tobacco finds (5 per 100 prisoners)

The prison is covered in photos of Wales and the countryside, everywhere you look there is a motivational quote, there are flowers, bees, greenhouses yet one in 4 prisoners didn’t feel safe.

Comfy chairs in reception, pretty pictures, colourful décor does not appear to contribute to the safety of HMP Berwyn.

Motivational quotes such as “When a flower doesn’t bloom you fix the environment in which it grows not the flower” means nothing if a quarter of the population feel unsafe.

Prisons can be austere places, drab, filthy, old and not fit for purpose. But here we have a new prison with serious problems. There can be no excuse that these are teething problems, we are talking about peoples lives.

Remember the Berwyn Values?

V = value each other and celebrate achievements

A = act with integrity and always speak the truth

L = look to the future with ambition and hope

U = uphold fairness and justice in all we do

E = embrace Welsh language and culture

S = stick at it

Is this just a marketing ploy, designed for a feel-good factor, making us all think that the money spent on this Titan prison was worth every penny?

Independent monitors have praised the work of staff at HMP Berwyn describing their efforts to establish a new prison as a ‘considerable achievement” (Recent comment by IMB) After this shocking report, what will they now say? Or will they remain silent?

I don’t doubt there are some hard working, diligent and caring staff. In fact, I met some on my visit last year. But when the prison opened in 2017 over 90% of staff had never worked in a prison before. When you have prisoners arriving from over 60 prisons all with different regimes, you find they have far more experience of the prison estate than the majority of prison officers.

But more worryingly is that the Government is continuing with its programme of building new prisons. A new prison will be built in Wellingborough as part of the Government’s Prison Estate Transformation Programme. I’ve read gushing articles on how this prison will benefit the community etc, similar to when HMP Berwyn began construction. Just like HMP Berwyn there are many promises and opportunities, but theory and practice can be a million miles apart.

HMP Berwyn: Does it raise more questions than it answers?

A bright summer’s day. A short car journey, a train, 2 tubes, 2 more trains and I finally arrived after more than 5 hours of travelling, into Wrexham. I’ve come to HMP Berwyn. I’m here with an open mind and at the invitation of the No 1 Governor, Russell Trent.

HMP Berwyn is not very well signposted, it’s as if the locality is reluctant to admit such a place exists in their own backyard. On the way here, I asked some locals for their opinion on the prison, its location and its size given that it is not yet at full capacity. Many local people were hesitant in speaking about it. Others were really bemused when I said I was on my way there to meet the Governor.

“Well, they need to build a bigger car park”, one local said.

On arrival, from the outside, it resembles a business park not a prison.

Entering through large open doors I was greeted by a uniformed officer with a friendly face who showed me the lockers for my bag and phone, and the door to enter the prison. But it was the wrong door. I wasn’t asked why I was there or even who I was. I was sent back outside to another door, this time I approached a glass window and said I was here to see Russell Trent. Simple.

Unfortunately, the officer there had no record of my visit. Great start. I was then asked to put my driving licence onto the window, so they could read my name. Bingo, the glass screens opened, and I was inside.

I fully expected to be patted down. I wasn’t. I expected an officer to pass a wand over me. They didn’t. This surprised me.

The site is huge. I was immediately impressed by the overall cleanliness, both inside and out, the wide-open spaces between communities and grass, yes real grass, and flower beds. There was even a small area where they hold services of remembrance.

Berwyn Values

V = value each other and celebrate achievements

A = act with integrity and always speak the truth

L = look to the future with ambition and hope

U = uphold fairness and justice in all we do

E = embrace Welsh language and culture

S = stick at it

Sitting on a comfortable sofa opposite Number 1 Governor Russell Trent in his office, he pointed out the motivational quote on the wall.

“When a flower doesn’t bloom you fix the environment in which it grows not the flower”

But motivational quotes are everywhere throughout the prison, on stairwells, in corridors alongside photos of Wales. Another one that caught my eye was:

“You have got to be the change you want to see”

The Governor handed me a small pack of cards; each card represents a different Berwyn practice for each day of the month.

Day 1. We recognise achievements and celebrate successes #thankyou

Day 2. We actively listen to each other and make eye contact #respect

Day 3. We offer and ask for help and feedback #support

You get the idea.

This is a first, I have never brought anything out of a prison that I haven’t taken in and I have never seen such motivational material in quite the same way in any other prison I have visited. And I’ve been to every category of prison, more than once.

Having the opportunity to accompany Governor Trent as he did his rounds meant we could talk as we toured communities, healthcare, college, library, horticulture, accommodation, etc.

I watched as well as listened, as I always do, with my notebook at the ready for contemporaneous note taking. Governor Trent appears to be on the ball, knowing the names of the men and their sentence. Many politely came up to him with a query or problem they wanted resolving. If he didn’t have the answer, then he signposted or agreed to meet them later. I did find it odd when he was called “Russ” and even “Trenty”. I thought that was a bit over-familiar considering the whole ethos was of respect. Something didn’t quite add up.

I watched as well as listened, as I always do, with my notebook at the ready for contemporaneous note taking. Governor Trent appears to be on the ball, knowing the names of the men and their sentence. Many politely came up to him with a query or problem they wanted resolving. If he didn’t have the answer, then he signposted or agreed to meet them later. I did find it odd when he was called “Russ” and even “Trenty”. I thought that was a bit over-familiar considering the whole ethos was of respect. Something didn’t quite add up.

In various conversations, the name of a certain community came up more than once and so did the name of a member of staff. It appeared some men felt fobbed off by this individual. I chose not to probe this but preferred to watch how it was dealt with.

I was introduced to the prosocial model of behaviour, a rehabilitative culture, making big feel small, the principle of normality and much more. Yes, Governor Trent is driven and considering over 90% of frontline staff have never worked in a prison before he has to sell his regime not only to the men but to the staff also.

The Ministry of Justice is very good at musical chairs, moving leaders around the prison service. It makes me wonder how long Governor Trent will remain at Berwyn.

Can Berwyn culture function without him and will the vision live on without his oversight?

Or will the settling cracks be more prominent or permanent?

In March 2018 there was a Death in Custody at Berwyn. The Prison and Probation Ombudsman (PPO) is still investigating and this death is unclassified as the cause is not yet known. I will not jump to any conclusions.

What I can say is during my visit I neither saw nor heard nor smelled any signs of drug abuse or spice.

Health and Wellbeing

Page 12 of ‘Rehabilitative Culture at Berwyn‘ states that “promotion of health and wellbeing is the responsibility of all whether they are living or working at Berwyn”. I think that collective ownership like this is a good thing because it means that the sole responsibility is not just carried on the shoulders of the healthcare team. The reason why this is good is because it replicates what goes on in the wider society.

I saw team sports in action, outdoor gym equipment and the outdoor running track. One initiative that caught my interest was the ‘Governor’s Running Club’. Men were proudly wearing their t-shirts which they were entitled to have once they had attended 5 successive weeks. Governor Trent emphasised to me that it was more about the commitment than the fitness.

Whilst all this looks favourable, one question I still have is the level of staff sickness at Berwyn. In ‘Annual HM Prison and Probation Service digest: 2017 to 2018, Chapter 15 tables – Staff sickness absence’ for the period 1st April 2017 to 31st March 2018 there were 3,628 working days lost (see Table 15.1, Column U, Row 18). It raises a concern as to why this is, given that Berwyn is not at full capacity and new communities are only opened once sufficient staff are in place.

Purposeful Activity

It’s all very well having unlock at 08:15 and lockup at 19:15 but if the industries, education, workshops, purposeful activities are not there then what?

And what do we mean by purposeful activity?

I saw one of the workshops, sewing prison regulation towels. A monotonous task, processing the same off-white coloured towelling. I’ve seen the same activity in other prisons such as HMP Norwich. Why is this happening in Berwyn? If sewing is to be one of the “purposeful activities” then surely this could be expanded to sewing something less bland and uninteresting using acquired skills that may be genuinely useful on release. For example, Fine Cell Work showcases how this is possible both inside and after release with their post-prison programme.

In another workshop I saw, I felt I was looking at something more purposeful; it was a call centre, provided by Census Group, run by a woman who was keen to praise the men in her group. I could see how skills learned here could translate into meaningful employment on the outside as well as provide interest, variation and a challenge for those participating in this activity.

I briefly stepped into the College building housing the prison library. If it wasn’t for the jangling of keys you could have been in any educational institution.

Accommodation

Whereas I had expected the heat, because my visit was in August, I had not expected the temperature levels inside on the landings of the communities and in the rooms I visited. It must have been at least 30 degrees.

I had heard a lot about the rooms here and saw many photos. However, you need to walk in one to fully understand the scale. For the rooms which are single occupancy they are compact, but I’ve seen smaller. A raised bed, with storage underneath, a desk with monitor, a plastic moulded chair. It has a shower/toilet/wash basin in the corner with a short curtain acting as a screen. And a small safe for locking away any medical supplies and that’s your lot.

Unfortunately, with only 30% of the rooms in Berwyn built for single occupancy the majority of the men have to double up.