Home » Cat D

Category Archives: Cat D

Dichotomy of Lived v Learned Experience

I first stepped foot in a prison in 2010; I was invited to be a community witness for a victim awareness course at HMP/YOI Hollesley Bay, around 40 minutes’ drive from my home. The environment was unfamiliar and so were the attendees. At that time, I was approaching my final year at University studying for BSc (Hons) Criminology, as a mature student, and I needed to figure out what my next steps should be. Each presentation I prepared as part of my coursework steered towards the justice system, prisons in particular. The first being a 10 minute talk on the Corston Report, by Baroness Jean Corston, published in the light of 6 women dying within a year in Styal prison.

I still remember the feedback I received as it was rather disheartening “Who is interested in women in prison?”

It soon became clear to me that very few were interested in prisons at all, both fellow students and lecturers.

Undeterred I carried on, highlighting where possible the appalling issues within the prison estate.

So, 15 years on, I have had the privilege to visit every category of prison up and down the country including the Women’s estate. I have delivered training in prisons, monitored a Cat D prison and became the Chair of an Independent Monitoring Board (IMB), attended numerous prison art exhibitions, toured prisons on the invitation of Governors, watched graduation celebrations for those that have completed courses in a Cat B, listened to guest speakers in prison libraries, judged a debating competition in a Cat C, written and edited policy documents and have published countless blogs that have been read and shared in over 150 countries. I have tirelessly spoken out for reform, and my work has been mentioned in the House of Lords.

I have seen the desperation, and I have felt the fear in prison, yet I have never resided in a prison.

“Well, what do you know?”

This question often ringing in my ears, as though I have just popped in from another planet.

“You don’t have lived experience”

A statement that is levelled against me far too many times to remember along with being White, A woman and Middle class…etc.

“Why is your writing so negative, instead of writing about problems, come up with solutions?”

It’s true, I don’t have a certain kind of “lived experience”, I’ve never stood in court accused of a crime and pleaded guilty or not guilty. I’ve never attended court awaiting my fate when the sentence is being read out.

I have sat and watched trials in the Supreme Court, the High Court and the courts in my local area. I have attended inquests and have given evidence, but most importantly I have been there for others, in court, supporting and comforting.

We all have lived experiences in some form. Personal lived experience of the justice system gives valuable insight, but does it make you an expert?

Surely, we can all work together to bring about much needed reform in our all too often failing system.

I believe there is a place for all who share a desire, a passion and determination to transform our criminal justice system into a fairer and more just structure. To give those that are or have been in prison the tools to rebuild or even build their lives for the first time. To give hope and a future.

Should lived experience and learned experience go hand in hand?

Do you think both are credible experts to whom we should be listening?

However, recently we have read about an individual with lived experience that became a valuable member of a prominent reform organisation, given responsibilities and then defrauded their employer.

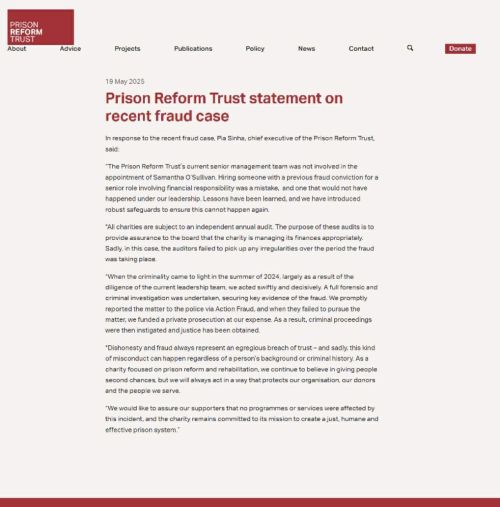

This wasn’t a small amount, it was over £300,000. The organisation – Prison Reform Trust (PRT). They had appointed an individual with a previous fraud conviction for a senior role involving financial responsibility. Little by little right under the nose of the board of trustees, with the then Chairman who is now the Minister of State for Prisons, Probation and Reducing Reoffending. The current CEO, the former Head of Women’s prison estate was quick to say: “We would like to assure our supporters that no programmes or services were affected by this incident, and the charity remains committed to its mission to create a just, humane and effective prison system”.

Basically the money wasn’t missed?

That quote came from this statement on 19 May 2025 which has now been removed from the PRT website, so I have included a screenshot of it.

So where were the safeguards?

This case reminded me of 2021 when I received the Prison Reform Trust (PRT) booklet to commemorate their 40 years, after having attended their celebration in London. A short time afterwards I read the former CEO of The Howard League, Frances Crooks (farewell) piece.

PRT and The Howard League are two organisations that work for reform, two organisations that basically admitted they had failed in what they set out to do.

So why is so much money ploughed into them through donations, grants, membership, and legacies?

Both have an annual salary bill of over £1M, astonishing isn’t it. Yes, they have initiated some important campaigns, but our prisons are still in crisis and reform is taking too long.

So, what is going wrong?

Does the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) squeeze organisations and charities by limiting their progress and their ability to instigate change? Many rely on either their approval or their funding.

As you can deduce, I’m not here to popularise organisations, or to popularise individuals.

I am fiercely independent and intend to stay that way.

But I have many questions.

Was the system designed to be ineffective or designed to perpetuate harm?

Should prison be a place for healing as I have heard others say, or a place for true reform of itself or individuals?

Do we try and change something that does not want to change, does not want reforming, where politicians gaze briefly at and when those in a position to do something, don’t?

It is a place where inspectors inspect and issue recommendations, a place where monitors monitor and issue recommendations.

Endless reports and endless reviews.

Endless round table meetings.

New committees formed.

Let’s just step away for a moment.

I hear big voices, big egos and big personalities shout out, but no one can hear anything anymore.

Has society closed their ears to the noise?

Has society closed their eyes to the mess?

I will say again “Our prisons are in crisis and reform is taking too long”

Vision is often personal, but a cause is bigger than any one individual

People don’t generally die for a vision, but they will die for a cause

Vision is something you possess, a cause possess you

Vision doesn’t eliminate the options; a cause leaves you without any options

A good vision may out live you, but a cause is eternal

Vision will generate excitement, but a cause generates power

[Adapted from Houston (2001)]

You can have lived or learned experience, but what is your cause?

If the cause is yourself, this is not true reform, it is perpetuating the system with a sense of power.

If you have a cause and integrity you are seen as an interrupter.

But the greatest power is humility either lived or learned.

Guest blog: Being visible: Phil O’Brien

An interview with Phil O’Brien by John O’Brien

Phil O’Brien started his prison officer training in January 1970. His first posting, at HMDC Kirklevington, in April 1970. In a forty-year career, he also served at HMP Brixton, HMP Wakefield, HMYOI Castington, HMP Full Sutton, HMRC Low Newton and HMP Frankland. He moved through the ranks and finished his public sector career as Head of Operations at Frankland. In 2006, he moved into the private sector, where he worked for two years at HMP Forest Bank before taking up consultancy roles at Harmondsworth IRC, HMP Addiewell and HMP Bronzefield, where he carried out investigations and advised on training issues. Phil retired in 2011. In September 2018, he published Can I Have a Word, Boss?, a memoir of his time in the prison service.

John O’Brien holds a doctorate in English literature from the University of Leeds, where he specialised in autobiography studies.

You deal in the first two chapters of the book with training. How do you reflect upon your training now, and how do you feel it prepared you for a career in the service?

I believe that the training I received set me up for any success I might have had. I never forgot the basics I was taught on that initial course. On one level, we’re talking about practical things like conducting searches, monitoring visits, keeping keys out of the sight of prisoners. On another level, we’re talking about the development of more subtle skills like observing patterns of behaviour and developing an intimate knowledge of the prisoners in your charge, that is, getting to know them so well that you can predict what they are going to do before they do it. Put simply, we were taught how best to protect the public, which includes both prisoners and staff. Those basics were a constant for me.

Tell me about the importance of the provision of education and training for prisoners. Your book seems to suggest that Low Newton was particularly successful in this regard.

Many prisoners lack basic skills in reading, writing and arithmetic. For anyone leaving the prison system, reading and writing are crucial in terms of functioning effectively in society, even if it’s only in order to access the benefits available on release.

At Low Newton, a largely juvenile population, the education side of the regime was championed by two governing governors, Mitch Egan and Mike Kirby. In addition, we had a well-resourced and extremely committed set of teachers. I was Head of Inmate Activities at Low Newton and therefore had direct responsibility for education.

The importance of education and training is twofold:

Firstly, it gives people skills and better fits them for release.

Secondly, a regime that fully engages prisoners leaves less time for the nonsense often associated with jails: bullying, drug-dealing, escaping.

To what extent do you believe that the requirements of security, control and justice can be kept in balance?

Security, control, and justice are crucial to the health of any prison. If you keep these factors in balance, afford them equal attention and respect, you can’t be accused of bias one way or the other.

Security refers to your duty to have measures in place that prevent escapes – your duty to protect the public.

Control refers to your duty to create and maintain a safe environment for all.

Justice is about treating people with respect and providing them with the opportunities to address their offending behaviour. You can keep them in balance. It’s one of the fundamentals of the job. But you have to maintain an objective and informed view of how these factors interact and overlap. It comes with experience.

What changed most about the prison service in your time?

One of the major changes was Fresh Start in 1987/88, which got rid of overtime and the Chief Officer rank. Fresh Start made prison governors more budget aware and responsible. It was implemented more effectively at some places than others, so it wasn’t without its wrinkles.

Another was the Woolf report, which looked at the causes of the Strangeways riot. The Woolf report concentrated on refurbishment, decent living and working conditions, and full regimes for prisoners with all activities starting and ending on time. It also sought to enlarge the Cat D estate, which would allow prisoners to work in outside industry prior to release. Unfortunately, the latter hasn’t yet come to pass sufficiently. It’s an opportunity missed.

What about in terms of security?

When drugs replaced snout and hooch as currency in the 1980s, my security priorities changed in order to meet the new threat. I had to develop ways of disrupting drug networks, both inside and outside prison, and to find ways to mitigate targeted subversion of staff by drug gangs.

In my later years, in the high security estate, there was a real fear and expectation of organised criminals breaking into jails to affect someone’s escape, so we had to organise anti-helicopter defences.

The twenty-first century also brought a changed, and probably increased, threat of terrorism, which itself introduced new security challenges.

You worked in prisons of different categories. What differences and similarities did you find in terms of management in these different environments?

Right from becoming a senior officer, a first line manager at Wakefield, I adopted a modus operandi I never changed. I called it ‘managing by walking about’. It was about talking and listening, making sure I was there for staff when things got difficult. It’s crucial for a manager to be visible to prisoners and staff on a daily basis. It shows intent and respect.

I distinctly remember Phil Copple, when he was governor at Frankland, saying one day: “How do you find time to get around your areas of responsibility every day when other managers seem tied to their chairs?” I found that if I talked to all the staff, I was responsible for every day, it would prevent problems coming to my office later when I might be pushed for time. Really, it was a means of saving time.

The job is the same wherever you are. Whichever category of prison you are working in, you must get the basics right, be fair and face the task head on.

The concept of intelligence features prominently in the book. Can you talk a bit about intelligence, both in terms of security and management?

Successful intelligence has always depended on the collection of information.

The four stages in the intelligence cycle are: collation, analysis, dissemination and action. If you talk to people in the right way, they respond. I discovered this as soon as I joined the service, and it was particularly noticeable at Brixton.

Prisoners expect to be treated fairly, to get what they’re entitled to and to be included in the conversation. When this happens, they have a vested interest in keeping the peace. It’s easy to forget that prisoners are also members of the community, and they have the same problems as everyone else. That is, thinking about kids, schools, marriages, finances. Many are loyal and conservative. The majority don’t like seeing other people being treated unfairly, and this includes prisoner on prisoner interaction, bullying etc. If you tap into this facet of their character, they’ll often help you right the wrongs. That was my experience.

Intelligence used properly can be a lifesaver.

You refer to Kirklevington as an example of how prisons should work. What was so positive about their regime at the time?

It had vision and purpose and it delivered.

It was one of the few jails where I worked that consistently delivered what it was contracted to deliver. Every prisoner was given paid work opportunities prior to release, ensuring he could compete on equal terms when he got out. The regime had in place effective monitoring, robust assessments of risk, regular testing for substance abuse and sentence-planning meetings that included input from family and home probation officers.

Once passed out to work, each prisoner completed a period of unpaid work for the benefit of the local community – painting, decorating, gardening etc.

There was excellent communication.

The system just worked.

The right processes were in place.

To what extent do you feel you were good at your job because you understood the prisoners? That you were, in some way, the same?

I come from Ripleyville, in Bradford, a slum cleared in the 1950s. Though the majority of people were honest and hardworking, the area had its minority of ne’er-do-wells. I never pretended that I was any better than anyone else coming from this background.

Whilst a prisoner officer under training at Leeds, I came across a prisoner I’d known from childhood on my first day. When I went to Brixton, a prisoner from Bradford came up to me and said he recognised me and introduced himself. I’d only been there a couple of weeks. I don’t know if it was because of my background, but I took an interest in individual prisoners, trying to understand what made them tick, as soon as I joined the job.

I found that if I was fair and communicated with them, the vast majority would come half way and meet me on those terms. Obviously, my working in so many different kinds of establishments undoubtedly helped. It gave me a wide experience of different regimes and how prisoners react in those regimes.

How important was humour in the job? And, therefore, in the book?

Humour is crucial. Often black humour. If you note, a number of my ex-colleagues who have reviewed the book mention the importance of humour. It helps calm situations. Both staff and prisoners appreciate it. It can help normalise situations – potentially tense situations. Of course, if you use it, you’ve got to be able to take it, too.

What are the challenges, as you see them, for graduate management staff in prisons?

Credibility, possibly, at least at the beginning of their career. This was definitely a feature of my earlier years, where those in the junior governor ranks were seen as nobodies. The junior governors were usually attached to a wing with a PO, and the staff tended to look towards the PO for guidance. The department took steps to address this with the introduction of the accelerated promotion scheme, which saw graduate entrants spending time on the landing in junior uniform ranks before being fast-tracked to PO. They would be really tested in that rank.

There will always be criticism of management by uniform staff – it goes with the territory. A small minority of graduate staff failed to make sufficient progress at this stage and remained in the uniform ranks. This tended to cement the system’s credibility in the eyes of uniform staff.

Were there any other differences between graduate governors and governors who had come through the ranks?

The accelerated promotion grades tended to have a clearer career path and were closely mentored by a governor grade at HQ and by governing governors at their home establishments and had regular training. However, I lost count of the number of phone calls I received from people who were struggling with being newly promoted from the ranks to the governor grades. They often felt that they hadn’t been properly trained for their new role, particularly in relation to paperwork, which is a staple of governor grade jobs.

From the point of view of the early 21stC, what were the main differences between prisons in the public and private sectors?

There’s little difference now between public and private sector prisons. Initially, the public sector had a massive advantage in terms of the experience of staff across the ranks. Now, retention of staff seems to be a problem in both sectors. The conditions of service were better in the public sector in my time, but this advantage has been eroded. Wages are similar, retirement age is similar. The retirement age has risen substantially since I finished.

In my experience, private sector managers were better at managing budgets. As regards staff, basic grade staff in both sectors were equally keen and willing to learn. All that staff in either sector really needed was purpose, a coherent vision and support.

A couple of times towards the end of your book, you hint at the idea that your time might have passed. Does your approach belong to a particular historical moment?

I felt that all careers have to come to an end at some point and I could see that increasing administrative control would deprive my work of some of its pleasures. It was time to go before bitterness set in. Having said that, when I came back, I still found that the same old-fashioned skills were needed to deal with what I had been contracted to do. So, maybe I was a bit premature.

My approaches and methods were developed historically, over the entire period of my forty-year career. Everywhere I went, I tried to refine the basics that I had learned on that initial training course.

Thank you to John O’Brien for enabling Phil to share his experiences.

~

HMP/YOI Hollesley Bay: should alarm bells be ringing?

We have heard from the Secretary of State for Justice, David Gauke and the Prisons Minister, Rory Stewart that we need to get back to basics where prisons are concerned. HMP/YOI Hollesley Bay is no exception.

Reading through the latest Inspectorate report shows clearly that only 15 of the 30 recommendations from the previous inspection in 2014 have been carried out.

Should alarm bells be ringing?

There are four tests for a healthy prison

- Safety

- Respect

- Purposeful Activity

- Rehabilitation and release planning (previously Resettlement)

Comparing the two latest reports, I noticed that some aspects once regarded as a safety issue are now a respect issue such as basic living conditions and making available a court video link. Probably why the recommendations in that category has fallen from 9 to 4. Looks good on paper but you have to read between the lines.

Four years ago, there were no recommendations for purposeful activity yet this time there are 5. From making sure prisoners get impartial careers advice, to providing detailed and constructive feedback on practical work to help prisoners improve, to ensuring that those engaged in prison industries are able to study and achieve qualifications related to their job. The answer is in the name “Purposeful” activity not just something to pass the long often monotonous days.

Surely these are basics of an open Cat D prison and is HMP/YOI Hollesley Bay failing?

It is worrying that there are many arriving at the prison without an up to date risk and needs assessment. Likewise, is the number of prisoners sent back to closed conditions, approx. 15 per month with some decisions not clearly evidenced.

And yet there are those that are released with little or no sustainable accommodation and this isn’t sufficiently monitored by the CRC’s.

With only one mental health staff, weak public protection procedures and with already 10% presented as medium or high risk to children there needs to be some serious changes before the planned arrival of those convicted of sex offences.

“New prisoners who potentially posed a risk to children were not always promptly assessed, and contact restrictions were not always applied in the interim”

There are so many issues to flag up:

“The anti-bullying representatives’ role was unclear, poorly advertised and lacked formal training”

“The strategic management of equality was less well developed than at the time of the previous inspection. There was no local equality and diversity strategy and the equality action plan was limited. There were no specific consultation groups running for prisoners with protected characteristics, other than the equality action team meeting”

The latest report shows increase in drug misuse with prisoners moving away from new psychoactive substances (NPS) and that cannabis was now the preferred drug. In addition the use of cocaine and steroids was an emerging problem.

Can HMP/YOI Hollesley Bay adapt to the changing needs and problems?

Let’s hope we are not seeing the gradual demise of this prison.

Recommendations 2018 inspection

Safety

- All use of force incidents should be scrutinised by senior staff to ensure that force is only used as a last resort.

- Body-worn cameras should be used during all use of force incidents.

- Risk assessments to determine if a return to closed conditions is necessary should be multidisciplinary and should show sufficient exploration of all relevant factors relating to the risks presented.

- Decisions to use handcuffs should be based on an individual risk assessment. (Repeated recommendation 45)

Respect

- The negative perceptions expressed by some prisoners that a small number of staff were punitive in their approach towards them should be explored and addressed.

- Basic living conditions on the Bosmere unit should be improved to ensure decency, including refurbished and well-maintained showers.

- Prisoners’ views about the quality of the food should be explored in greater depth and, where possible, changes should be made to increase their level of satisfaction.

- The issues with the prison shop should be resolved, so that prisoners receive their correct order.

- A court video link should be available. (Repeated recommendation 3)

- The prison should routinely consult prisoners in the protected groups to ensure that their concerns and needs are identified and, where possible, addressed. (Repeated recommendation 25)

- Managers should consider both local and national equality monitoring data, and address inequitable outcomes.

- Reasonable adjustments for prisoners with disabilities should be swiftly completed. These prisoners should have access to practical support, such as a buddy scheme, which supports them in their day-to-day life at the prison

- There should be a regular health care representative forum to inform service developments and enable collective concerns to be addressed.

- There should be regular, systematic health promotion campaigns delivered in conjunction with the prison.

- Prisoners should have timely access to optician and dental services. (Repeated recommendation 68)

- There should be a memorandum of understanding and information sharing agreement between agencies, to outline appropriate joint service working on social care.

Purposeful Activity

- Prison managers should ensure that they have accurate information on the education, training or employment that prisoners enter following their release, so that they can evaluate and monitor fully the impact of the curriculum on offer.

- Prison managers should ensure that prisoners receive impartial careers advice and guidance when they arrive at the establishment and throughout their time in custody, so that they can plan their future after release more effectively.

- Prison and People Plus managers should ensure that vocational tutors provide detailed and constructive feedback on practical work, to help prisoners to improve.

- Prison and People Plus managers should ensure that vocational tutors challenge prisoners to achieve high standards of professional workmanship that meets commercial expectations.

- Prison managers should ensure that prisoners engaged in prison industries have an opportunity to study and achieve a qualification related to their job.

Rehabilitation and release planning

- Visits provision should meet demand.

- Prisoners on resettlement day release to maintain family ties should not be required to be collected and returned by family members in a car unless the risk assessment suggests that this is necessary.

- The prison’s needs analysis should make full use of offender assessment system (OASys) and P-NOMIS data, in order to identify and address gaps in provision.

- Prisoners should only transfer to open conditions once a full and up-to-date assessment of their risk and needs has been carried out.

- There should be sufficient places available in Bail Accommodation and Support Service accommodation to allow prisoners to be released on home detention curfew on their eligibility date.

- Meetings to discuss a prisoner’s suitability for open conditions should be multidisciplinary. Decisions to return prisoners to closed conditions should be clearly evidenced and defensible.

- For prisoners returning to closed conditions, recategorisation to C should be supported by clear evidence.

- The prison should undertake a comprehensive analysis of needs, to establish the range of offence-focused interventions required.

- The community rehabilitation company (CRC) should monitor the number of prisoners released to sustainable accommodation (12 weeks after release), to understand the effectiveness of provision.

- The CRC should ensure that interviews to review resettlement plans are conducted by a trained member of staff.

Recommendations 2014 inspection

Safety

- Recommendation: The Bosmere unit should be upgraded or replaced with permanent accommodation

- Recommendation: OASYs and ROTL procedures should be sufficiently rigorous to ensure risks to the public are effectively managed.

- A court video link should be available.

- Prisoners should receive a private first night interview with a member of staff.

- The prison should investigate prisoners’ perceptions about safety and address any concerns raised.

- The safeguarding adults framework document should be finalised and staff should understand safeguarding procedures for adults at risk.

- Decisions to use handcuffs should be based on an individual risk assessment.

- The drug strategy action plan should be updated, inform developments and detail lines of accountability.

- The controlled drugs administration room should be more welcoming and security arrangements should be in line with what is required in open conditions.

Respect

- The shower areas in the Stow unit should be refurbished.

- Staff and personal officers in the Bosmere unit should check on and interact with prisoners in their care.

- The EAT should investigate when monitoring data consistently suggests inequitable outcomes for minority groups.

- The prison should routinely consult prisoners in the protected groups to ensure their concerns and needs are identified, and where possible, addressed.

- Suitable adapted accommodation should be available for prisoners with disabilities.

- All staff should have regular managerial and clinical supervision, as well as appropriate continuing professional development underpinned by a current performance appraisal.

- There should be sufficient clinical rooms to provide a comprehensive service and all areas, including the dental suite, should comply with infection control guidelines.

- Triage algorithms should be available to ensure decisions made are consistent and appropriate.

- Prisoners should have timely access to optician and dental services.

- Prisoners should have access to pharmacist-led counselling sessions, clinics and medication reviews.

- The dental service should be informed by an up-to-date needs assessment.

- Custodial staff should receive regular mental health awareness training.

- Self-catering facilities should be improved, particularly for prisoners on long or indeterminate sentences.

- There should be no administration charge for catalogue orders.

Resettlement

- Formal supervision should be provided to all OSs.

- Sentence planning objectives should be specific and focused on outcomes.

- All prisoners should have planned case management meetings with their OS proportionate to their risk and needs. Meetings should be recorded.

- When prisoners are returned to closed conditions there should be a clear record of who made the decision and the rationale for it; re-categorisation from D to C should only take place if there is clear evidence that this is required.

- The content and information on the virtual campus should be reviewed to ensure it is relevant for prisoners looking for work on release.

- There should be robust discharge planning processes in place to ensure continuity of care.

- The prison should develop a strategic action plan that aims to ensure all prisoners have the opportunity to stay in contact with family and friends.

Over 60,000 allocated visits in prisons by the IMB

Did you know that there are between 60-65,000 allocated visits by the IMB to Prisons and Immigration Removal Centres each year?

This allocation is dependent on the money available for expenses such as travel and subsistence. But that is not the actual number of visits.

I can reveal to you for the first time that since April 2016 HMP/YOI Hollesley Bay, an open Cat D prison, only achieved 58% of its allocated visits.

That cannot be effective monitoring and yet the MoJ has repeatedly told me that effective monitoring is going on there. Really?

How many more prisons do not satisfy their allocations?

If the projected percentage of allocated visits turns out to be 58% in terms of actual visits across the custodial estate then monitoring in YOIs, HMPs and IRCs is dangerously low. It also means that this part of the National Preventative Mechanism (NPM) is dysfunctional.

The IMB is very topical on Twitter now and that’s not just because of my story.

There are many vacancies on boards from Cat D open prisons to closed and remand prisons. It’s not a glamorous job, you need passion, determination, time, and a true interest in the welfare of prisoners and the mechanisms of the prison estate. Oh and you won’t get paid, there are no guarantees that your voice will be heard and there is a lack of support from IMB Secretariat. If you can get beyond all that, apply.

Some IMB members only visit wings to retrieve applications from the IMB boxes and perhaps to speak to those that have asked to see them. But if the IMB members are regarded by prisoners as practically useless, having no influence and are part of the MoJ then what are tax payers paying for?

Annual Reports

Every IMB is required to write an Annual Report. However, by the time it is published it is so out of date that it precludes any chance of swift meaningful action to resolve issues and will be filed away to collect dust just as previous years.

Am I being harsh? NO.

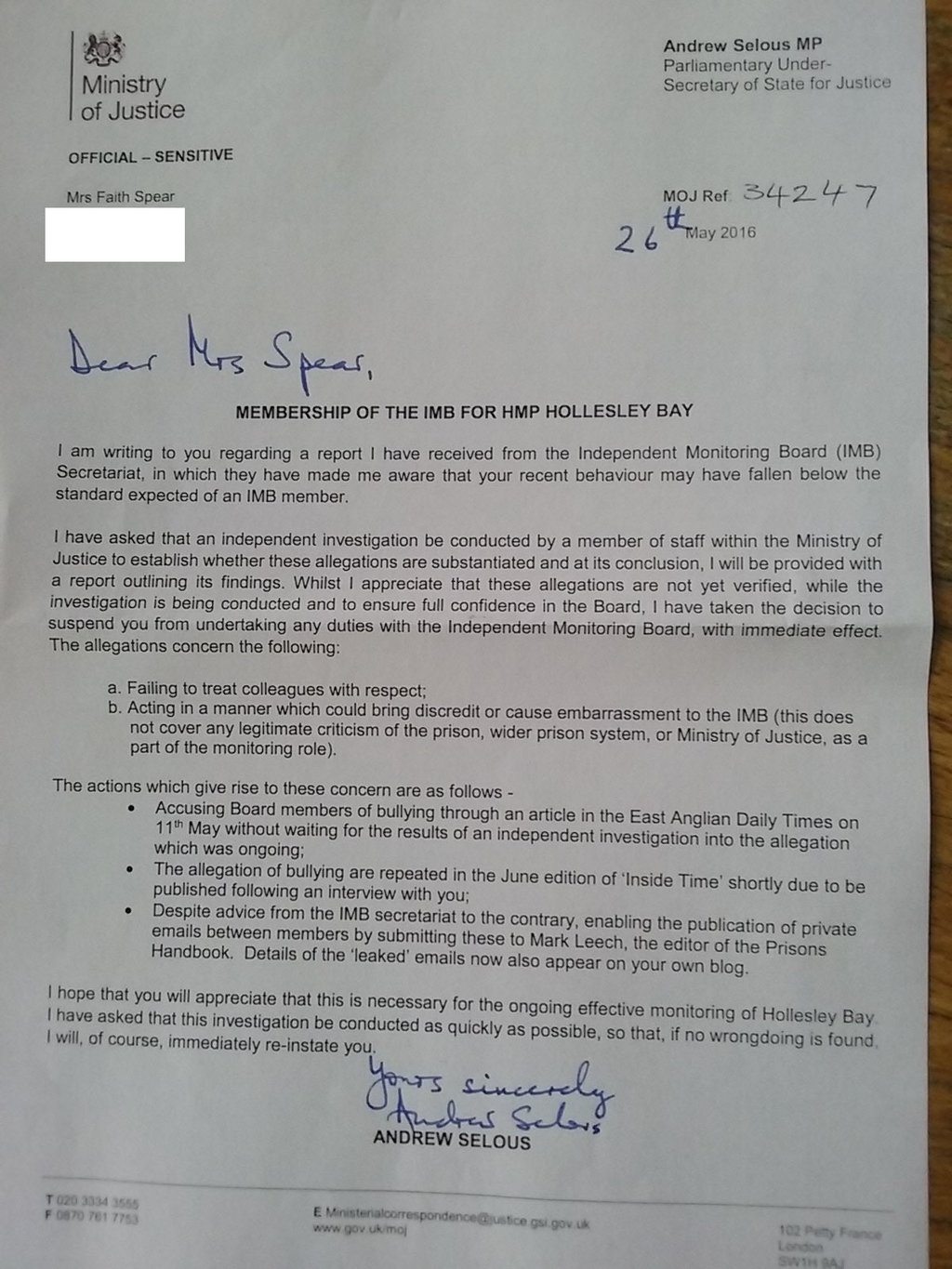

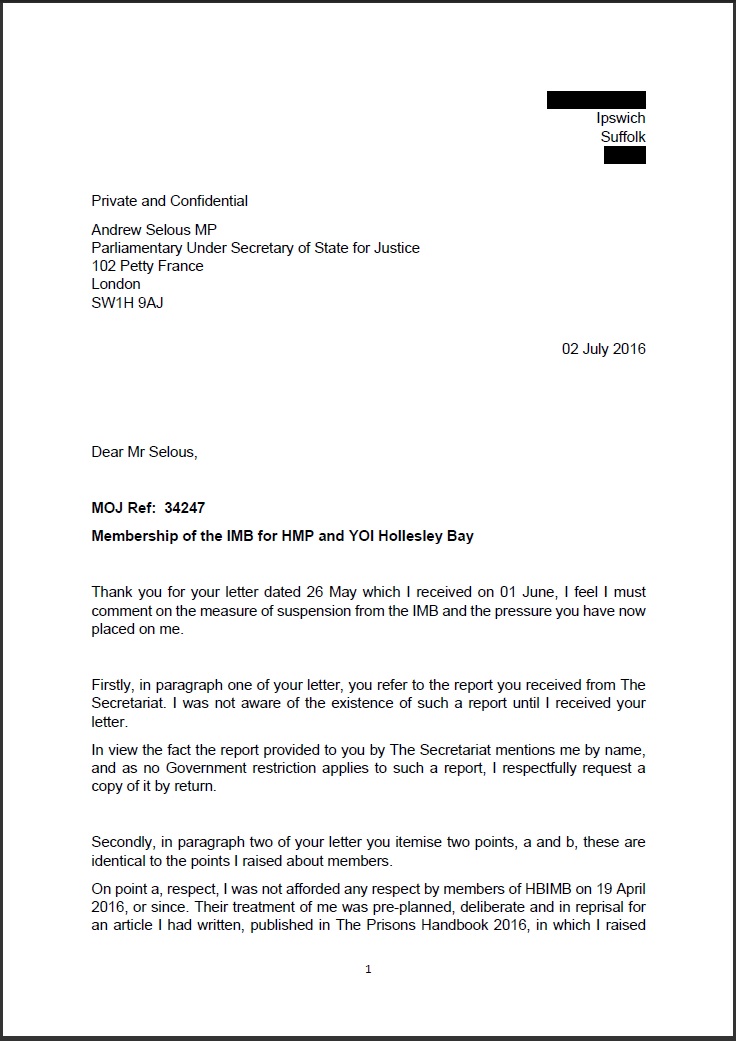

I have spent hours and hours preparing, collating, and writing Annual Reports. I was determined that the 2015/16 Annual Report for HMP/YOI Hollesley Bay would be different, that it would not be cut and paste as previous years. But there will be no Annual Report for 2015/16. I don’t even know where all the preparations went it was abandoned when the HBIMB ambushed me on 19th April and ostracised me in reprisal for speaking out for reform.

I recently learned that HMP Doncaster didn’t publish an Annual Report and it does not even have an IMB board. When the Chair left the board followed and it then had to rely on members from other prisons dual boarding.

So how many other IMB’s are suffering from similar dilemmas?

Updated 07 March 2017

Its even worse at HMP/YOI Hollesley Bay than I revealed when I posted this blog on Sunday.

Information made available to me show new figures for the actual number of visits is even lower.

Allocated visits were 354 actual were 204. New figures allocated visits 354 actual were 196.

Just 55%, Lousy performance means that when monitoring is not effective it places people in custody and people who work there at higher risk.

Why this Daisy is no shrinking violet!

A situation update for those of you closely watching this debacle.

Firstly, thank you for the many, many messages of support.

Two HBIMB members resigned this week and at the monthly Board meeting yesterday I was the only one present. Sure, four Board members did email in their apologies – all within 10 minutes of each other – and two others decided not to contact me.

How many daisies can you see in this photo?

One HBIMB member in particular is incredibly hostile towards me and, again, I am being told I brought it on myself.

I don’t understand why they are so blinkered; this job needs people who look at the bigger picture.

But I have assured the Governing Governor of HMP/YOI Hollesley Bay that independent monitoring will continue to be done.

At the moment, I am awaiting the outcome of the Independent investigation by the MoJ into how I was treated at the Board meeting on 19th April.

Last week, we had the Secretary of State for Justice addressing the Governing Governors’ Forum.

Today we had the Queen’s Speech (see paragraphs 21-23 on prison reform) and the publication of Dame Sally Coates’ report Unlocking Potential: a review of education in prison.

Prison reform is front and centre of the political agenda. There’s no better time.

So why is it that the IMB is so reluctant to move on, to become more relevant and to have a stronger voice?

I certainly don’t regret making a stand, I did nothing wrong, but it has been and still is at great personal cost.

The situation continues.

~