Home » Articles posted by faithspear (Page 3)

Author Archives: faithspear

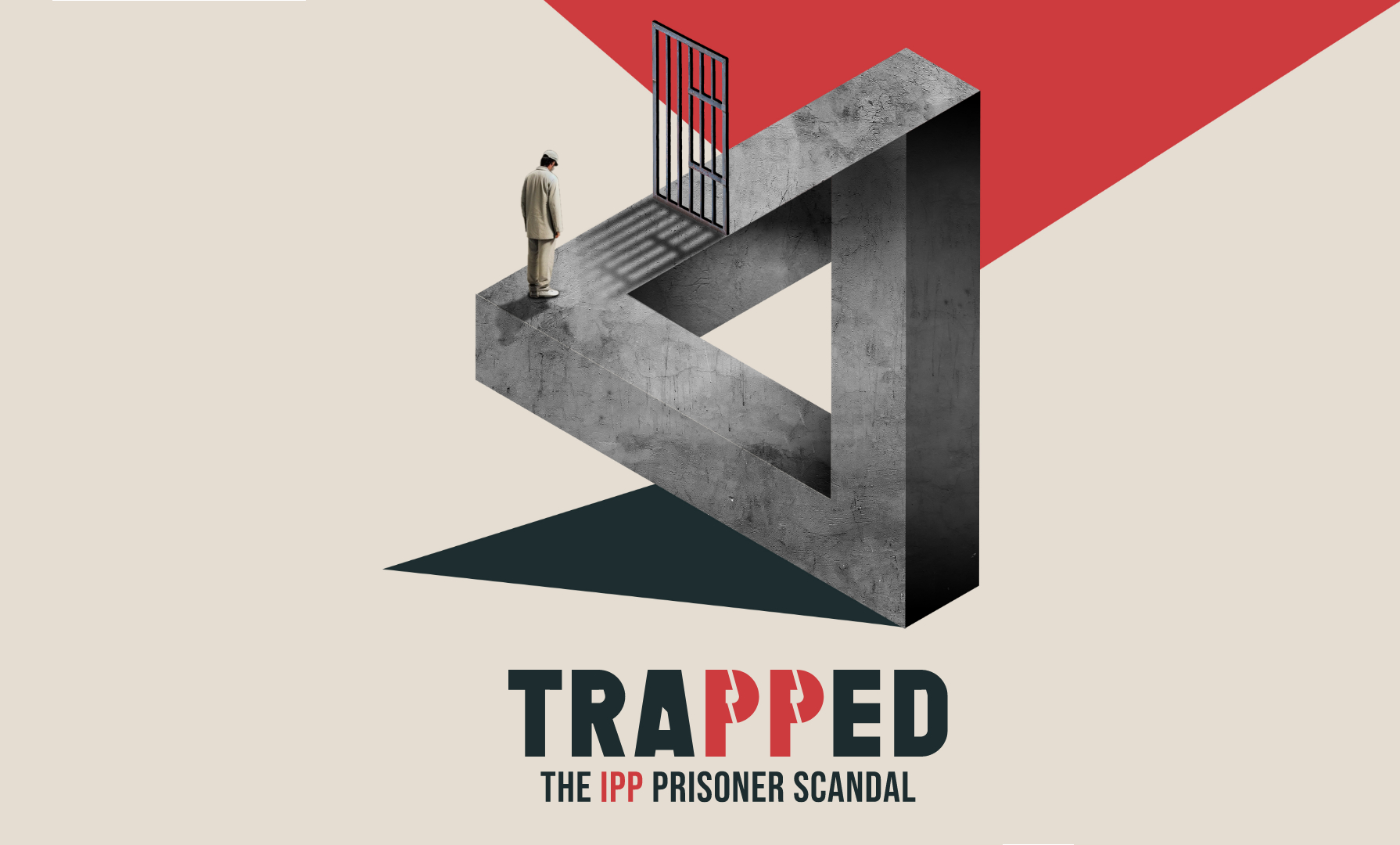

Let’s end this injustice now, TOGETHER: IPP Scandal

The momentum is building, and more of society are becoming aware of the IPP Scandal, where prisoners can be languishing in prison with no end date to their sentence. Over 80 with an IPP sentence have taken their own life, their hope deferred time and time again. This sentence was abolished in 2012, but not retrospectively. Stories of those caught up in this tragedy in our justice system can be heard in a series of podcasts, by the Zinc Media Group. Click HERE for the link.

Sir Bob Neil MP has tabled an amendment to the Victims and Prisoners Bill to implement the recommendation of the Justice Select Committee to re-sentence all IPPs. In order for this to happen we need this amendment supported by the majority of MPs from all parties.

This is where we all can assist.

Firstly: click HERE to watch a film By Peter Stefanovic highlighting the injustice for those serving an IPP sentence. It has now been viewed over 2.5M times.

Secondly: repost this video and tag your MP. If you are not sure the name of your MP, click HERE to find out .

Thirdly: write to your MP. Below is a template produced by UNGRIPP, that can be used to encourage your MP to vote to accept the important amendment for re-sentencing.

Click HERE for the link and explanation of how to prepare and send, or copy and paste the sample letter below. Of course, if you do not have access to a printer or simply prefer to hand write letters, then feel free to use part of this sample letter. MPs pay particular attention to hand written letters.

{YOUR FULL NAME}

{YOUR FULL ADDRESS}

{YOUR POSTCODE}

{EMAIL ADDRESS}

{DATE}

Dear {MP NAME},

My name is {YOUR NAME} and I am a constituent of {YOUR CONSTITUENCY/AREA WHERE YOU LIVE}. I am writing to you because I would like to see changes made to the Indeterminate Sentence for Public Protection (known as the IPP sentence); a type of indefinite sentence given to 8,711 people between 2005 and 2013 for a wide range of major and minor crimes, and abolished by the Government in 2012. I have enclosed further information about the sentence, in case you are not already aware of it.

I would like you to take forward my concerns, set out below, by backing Amendment NC1 to the Victims and Prisoners Bill, proposed by Sir Bob Neill, Chair of the Justice Select Committee. The amendment, entitled ‘Resentencing those serving a sentence of Imprisonment for Public Protection’ would make provision a resentencing exercise carefully planned by an expert group. You can view the full amendment here: https://bills.parliament.uk/bills/3443/stages/17863/amendments/10008642

In August 2023, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture stated the Government should urgently review IPP. They expressed ‘serious alarm’ about the suicides of people serving an IPP sentence (a concern recently echoed by the Prison & Probation Ombudsman), and stated that the sentence ‘violates basic principles of fair justice and the rule of law.’

As a member of the public, I am concerned that thousands of people are still serving an abolished sentence condemned by an international human rights body on torture. I do not think such a sentence has any place in our justice system. As you may already be aware, the IPP sentence was abolished because it was agreed to be unjust and ineffective. Thousands of people were given a life sentence for crimes that would never attract a life sentence today. The sentence was based on the premise that we can accurately predict a person’s risk of committing future crime; something that is complex, difficult, and flawed. It is a stain on the reputation of our justice system that thousands of people are still subject to an abolished sentence, and have served years longer than the time it was agreed they deserved as punishment. It is also reprehensible that their families and children continue to suffer the consequences. {IF YOU WANT TO, ADD YOUR EXTRA THOUGHTS ON THE SENTENCE HERE, AND EDIT THE ABOVE TO REFLECT YOUR VIEWS}

In 2022, the Justice Select Committee published a report on their inquiry into the IPP sentence. The report gives a damning indictment of a regime of indefinite detention that has caused widely documented harm, and departed from public notions of justice, fairness and proportionality.

The Committee concluded that even though there are ways to improve how the IPP sentence works, there is no way to truly fix it, and it is “irredeemably flawed”. Their main recommendation is a resentencing exercise. That means that everybody serving IPP would be individually resentenced by a judge, to a sentence available under current sentencing law, following the principle of balancing public protection with justice, judicial independence, and the appointment of an independent panel to implement the exercise.

I would be grateful if you would speak to the Secretary of State for Justice, Alex Chalk and request that he consider the proposed amendment, as well as advocating for it yourself. Shadow Justice Minister Ellie Reeves signalled in a Westminster Hall debate on 27th April 2023 that Labour will work constructively with the Conservatives in a cross-party effort on this issue.

The upcoming proposed amendment to the Victims and Prisoners Bill is a window of opportunity to rectify the wrongs to a sentence that has been condemned by the European Court of Human Rights, the Prison Reform Trust, the Howard League, Liberty, Amnesty International, the former Home Secretary who introduced the sentence (Lord Blunkett), and the former Lord Chief Justice Lord Brown who has called it “the greatest single stain on our justice system”. Your help on this matter is crucial.

If you are unable to address this personally, I would like to request that you escalate my letter to the relevant Minister or department. Please do keep me informed of any progress made. I look forward to hearing from you.

Yours faithfully,

{YOUR NAME}

Finally: remember to show your support on social media for those campaigning hard for the vital change in re-sentencing all those trapped within the IPP sentence.

Thank you

TOGETHER we can end this injustice.

Public reaction to the IPP Scandal

On Monday 20th November, Peter Stefanovic, CEO, Campaign For Social Justice, said in a short film:

“Imagine a country where a man has spent 18 years in jail for trying to steal a coat or imprisoned for 11 years for stealing a mobile phone – sentences described by the United Nations as egregious miscarriages of justice it’s unthinkable & it’s happening in this country NOW”

Peter was referring to the Imprisonment for Public Protection (IPP) sentence, that has been described as “a stain on British justice” and was abolished in 2012.

This short video Peter put out on social media (X) has been viewed over 2.5M times. This is astonishing and shows the public reaction of shock, outrage, and disbelief.

On 28th September 2022, the Justice Select Committee, chaired by Sir Bob Neil MP, published a report calling for the Government to re-sentence all prisoners subject to IPP sentences. Unsurprisingly, Rt Hon Dominic Raab MP, the then Secretary of State for Justice, rejected this stating re-sentencing:

“could lead to the immediate release of many offenders who have been assessed as unsafe for release by the Parole Board, many with no period of supervision in the community”.

Then once again, a new Secretary of State for Justice, Rt Hon Alex Chalk KC MP even after the intervention from Dr Alice Edwards, United Nations special rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, still refused to re-sentence those on an IPP sentence.

An amendment to the Victims and Prisoners Bill, tabled by Sir Bob Neil MP to implement the Justice Select Committee’s recommendation to re-sentence all IPP’s will be considered by the Government shortly. This must be supported by the majority of MPs from all parties.

The latest podcast from Trapped: The IPP Prisoner Scandal Episode 9 entitled Set up to Fail, tells the stories of two women, Nicole and Madison on a life licence, both of which served a sentence way beyond their original tariff. Even after release, many on an IPP sentence feel that they are set up to fail and are constantly walking on eggshells. This episode also relays the story of the tragic suicide of Matthew, having been released since 2013. In a letter, he wrote:

“I am stuck in a never-ending cycle of which suicide is quite possibly really the only way out. Asking for help will go against me, not asking for help will most likely kill me”.

Many have lost hope and have taken their own lives.

The IPP sentence is breaking people, and the overwhelming support from the public to end this sentence cannot be ignored. The Government will only be held to account if the public makes its views known.

So many people think “well what can I do?”

My response to that is:

Contact your MP in writing and ask them to support this amendment.

Watch the film.

Listen to the Trapped podcasts.

Inform those around you of this cruel and inhuman sentence.

The IPP sentence: At an Inflection Point?

I have followed the Imprisonment for public protection (IPP) issue for over 10 years and seen how political inertia has stifled any chance of reform. But things are now changing. We are at an inflection point. To learn more, I listened to all episodes of the ‘Trapped: The IPP Scandal’ podcast series.

On 25 July 2023 one of its producers, Melissa Fitzgerald, contacted me and invited me to meet their entire team. This led to conducting an interview with two members, Hank Rossi (Consultant) and Sam Asumadu (Investigative Reporter).

10 minute read.

Faith: To what degree have you noticed how the IPP sentence has emerged as a major issue, and could even be stated as a tragedy within our Criminal Justice System?

Sam: I absolutely agree it’s a tragedy in our criminal justice system. Once you’ve done your original tariff, you’re basically being detained on what you might do rather than what you have done. To me, that’s something for science fiction, not a functional society. Preventative detention should not have had any place in British jurisprudence. The IPP sentence was abolished in 2012 on human rights grounds. Because it wasn’t retrospectively abolished, it’s meant that there’s this legacy and hangover of a particular time in British history, from the New Labour government.

Faith: You spoke with Lord Blunkett, was he dismissive or contrite in any way or genuinely mortified by the suffering caused by not only those given an IPP sentence but their families too. Could he have foreseen how this sentence would be implemented?

Sam: It’s hard to comprehend that this is where we are, over 80 people serving an IPP sentence have died in prison taking their own lives, so many people have been broken by what’s happened. Lord Blunkett has been quite vocal about the IPP, he has been contrite, and he has apologised. He does seem to care about the issue, whether that’s a matter of him thinking about his legacy or if it’s completely genuine, I don’t know. I can’t judge what’s in a man’s heart. However, it doesn’t quite matter how contrite he is because it’s still happened and a lot of lives have been destroyed and are still being destroyed, in my opinion. I think he believes that initially, at least, the judges were over applying the sentence to many people. I think it was just very bad legislation on his part and the Ministry’s part. You have to look at what may go wrong, the worst-case scenarios in legislation, because once it is out, it becomes part of bureaucracy, and into people’s hands. People are fallible, especially when it comes to prisons.

Faith: There were alternatives already. He didn’t need to bring in this new legislation.

Sam: He didn’t, but it did look good at the time. It sounded good as well and it was attractive to the people in the government. Finally, we’ll deal with the underclass.

Faith: How do you get beyond any concerns that you may have that your reporting will fall on deaf ears?

Sam: The series is a permanent record of what is an incredible failure of society. I think the authorities can’t hide from it now. We can send questions to Alex Chalk and Damian Hinds to keep pressure up, making sure they know people are watching. They can’t hide from us.

Faith: We are bombarded with messages from the media, be it on social media or in the newspapers. How do you get an audience to not just listen but act too?

Sam: Ultimately, it’s in their hands. We want people to act. What we’ve done is to highlight stories of people who are campaigning family members. They have little to no resources. Listening to that, I hope it makes people feel incumbent that they can do something themselves to help end this horrific tragedy. This could have happened to their family members too.

Faith: As a professional journalist you have an acute sense of right and wrong and fact from fiction. But has the topic of IPP gripped you because of any reason other than justice v injustice?

Sam: I can’t believe that the state thinks that they can keep on saying it’s “a stain on the British justice”, “stain on the conscience of the British Justice” and not rectify it. The state has a duty to care for prisoners whether they like it or not. Yet people have died and are dying on their watch. And I think that there should be some sort of accountability for that.

Faith: I understand prior to these podcasts, you were involved in a piece of research around IPPs with the Centre for Crime and Justice Studies (CCJS). Can you outline the part you played?

Hank: I funded Zinc Productions and we’ve hired Steve, Melissa, and Samantha to do this work. We’ve worked with quite a lot of the families and friends of IPP’s and with a number of IPP sentenced individuals as well. I started a process with the researchers at the Centre for Crime and Justice Studies (CCJS) in 2020. I approached them, having approached a number of criminal justice reform charities about this issue to fund some research on the possibility of an independent tribunal on IPP. Every time I looked further into this, I got more concerned. I almost, you know, started to become unwell myself, thinking this can’t be real.

One of the processes that I thought might help, was a sort of tribunal inquiry when power cannot hold itself to account because of nefarious activities of those who have it. You can get a group of citizens together and hold your own inquiry. That’s what I thought might be a useful way to look at the problems of IPP. Richard Garside and Roger Grimshaw from CCJS sat around the table with me and we came up with a plan to research the idea for an independent People’s Tribunal on indeterminate detention in the UK. That led to a document I was signing to invest some money in their work to research this idea.

I was sort of feeling like we’d achieved something just by having a conversation when so many people, organisations, and people in power were unwilling to talk about it. Richard and Roger took this seriously at the CCJS and we signed an agreement. The very next day, out of the blue, the government was going to be put under the spotlight by the Justice Select Committee as they launched their inquiry into IPPs.

Faith: Do you believe we live in a punitive society, which has then led to one of the flaws in the IPP sentence as assessing the dangerousness of each offender?

Hank: The short answer is yes. We live in a far too punitive society. I’ve just come across a document published by the Prison Reform Trust in 2003 where the writers are looking at sentence length and they’re worried that they are getting longer. Since then, we’ve gone to this extraordinary place now where a whole life tariff is an everyday thing. I call it the punitive ratchet. We are now learning about the significant harm that prison does to an individual. That’s perhaps what I would say about the punitive concept of prison. The way that we engage with it in the United Kingdom is toxic and has become more and more toxic in the 20 years since the millennium.

Assessing Dangerousness is a complex and very difficult business. You could argue that the assessments tools are inherently problematic because of the nature of prediction. That is a fundamental flaw in the idea of the IPP legislation in the first place to think that there was a system that you could implement to usefully predicts people’s behaviour in the future. And initially the whole process of IPP sentencing circumvented assessment for many. They were just labelled as dangerous based on the offence.

Faith: If you talk about dangerousness, this has changed throughout the sentence.

Hank: This is what annoys me endlessly about the fall back of “Oh, well, this person was a dangerous individual”, no, they weren’t necessarily in many of the cases. There is no evidence to me that people can be predictably relied upon to do the same thing in the future. You can say what a statistical likelihood is but that is nowhere near the same as knowing what someone will do. And we know that from the statistics, less than 1% of people go on to commit a serious further offence when they’ve been out of prison.

Faith: Is the IPP sentence a systemic miscarriage of justice?

Hank: Yes, that’s the best short description of it. Some people would say this is not a miscarriage of justice because that requires an individual to have been completely misrepresented in the process. There’s a researcher who calls these sort of events “errors of justice”. In other words, they are less clear. And there’s truth that these people who committed an offence should be punished by a prison sentence. How long they spend in jail should be part of that process. The idea of indefinite detention, that’s a no no. In international law, we shouldn’t do that.

Faith: With the pressure mounting for Alex Chalk the Secretary of State for Justice to act, how hopeful are you that there will finally be a breakthrough?

Hank: I am hopeful. There is action that people are taking and movement in the system. It’s a systemic problem, and what I know about systems theory is that you might have to take multiple approaches to shift a problem in a system. Unfortunately, when people say, well, how do you fix that? they say, well, you have to go through the legislative body and that’s our parliament. And parliament is a complicated place.

Alex Chalk is in the hot seat right now, and I know he’s really feeling it. There are things he could do tomorrow through LASPO (Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012) to make this go away using executive powers. He’s chosen not to use those at this point. We’ll see if there’s continuing pressure from campaigners and from international bodies. Maybe he will be pushed to do more. But the problem is that under international law, this must be looked at on a case-by-case basis. Well, there’s 3000 people in prison to consider on a case-by-case basis. It’s a nightmare. So, we need some executive action. But I have a feeling that things will happen.

Following on from what Sam was saying, I agree this is the most egregious example of state violence I’ve come across in the UK in my lifetime. I’m over 50 years old. People have been persecuted in a way that I’ve never imagined in this country. The IPP sentence is toxic. It’s extraordinary that the system we have has not been able to rectify that. It leads me to believe that we have a very weak parliamentary democracy. Essentially the power of the executive to keep this going when it should not keep going, is too much. There’s something going wrong within the structure with the roles and the regulations of how parliament and our democracy work.

One thing that I’ve concluded is instrumental perhaps, and was talked about 15 years ago, was the merging of the role of the Lord Chancellor with the role of the Minister of Justice, When that job was boiled down into one, you end up with a problem of separation of powers, I think. And that’s a fundamental problem. So that’s something for us to think about in the future.

Faith: I had lunch recently with Shirley de’Bono where she shared with me her next step in her campaign for IPP prisoners being released, to go to the United Nations in Geneva to have discussions with Dr Alice Edwards, Special Rapporteur on torture. I believe you went along too.

Hank: I’ve been communicating and collaborating with quite a number of different people in different organisations, and I wasn’t expecting to be invited. In the week before a meeting was set up, I was invited to attend in Geneva with Dr. Alice Edwards and Shirley de’Bono and others, and the conversation was about what is going on and what might be done. Shirley presented several cases. I mean, just this is a horror show, isn’t it? You can’t make it up. I’m as worried about this as I have been about anything in my life. I lose sleep over this. And I think that this is an important moment. In Geneva more information was sought by the Special Rapporteur and indications were given that statements will be made in the future that perhaps will certainly shame the United Kingdom’s government on the international stage.

Faith: Do you think the UK government should take any notice of the United Nations, and if so, how much pressure should the United Nations place on the UK government?

Hank: The United Kingdom being a signatory to the Optional Protocol on the Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (OPCAT) is a powerful thing. We’ve agreed to do certain things to honour certain international standards, and we’re not doing that. And the fact that this hasn’t been noticed for a decade is shocking. But going back to the torture problem, the United Nations has clear guidelines on this. We’re breaking many of them.

The United Nations doesn’t have legal or legislative making powers, but it has influence. On 30th of August the United Nations special rapporteur on torture made a statement condemning this situation. I believe they’ve sent a letter to our government and their response will have to have sent in before the 23rd of November, when we should hear what the letter said. We won’t know until then perhaps exactly what’s going on, but it’s all very useful in putting pressure on our government.

Faith: In your opinion, should the UK withdraw its signature from OPCAT because the very existence of an IPP sentence, which we know inflicts psychological harm, and psychological harm is a form of torture, does not align with its agreement to OPCAT?

Hank: I think we need to be part of this. And the whole point of mechanisms where someone can criticise you is useful. In some organisations you create a specific chain of responsibilities and it’s often known as “just culture” where whistleblowing is encouraged, and recriminations are not expected if someone highlights a concern. But in this system, we’ve have had the opposite, that the snuffing out of criticism and the silencing of objections has been part of why this has gone on so long. And that’s got to stop. The National Preventative Mechanism (NPM) has 21 agencies appointed by our government to fulfil the obligations under OPCAT. These agencies have certain powers and they’re not using them properly. Also, the independence of them is questionable. Is it time for a review of the NPM?

Three years ago, I introduced the idea of a people’s tribunal on indefinite detention to the Centre for Crime Justice Studies. We’ve weighed up whether there was any need for a tribunal process, if the Justice Committee made these very strong recommendations that change was needed, of course that’s very positive. But what we’ve found is that the government is not interested, and Parliament seems to have gone along with it. There are indications there’s going to be a bit of noise in Parliament about the Victims and Prisoners Bill. The international community are now waking up like a sleeping giant and the possibility of an independent process to hold government to account and to make a record of the situation is still an idea.

Using Disaster Incubation Theory, we can look at this crisis as an unfolding sequence of events, which was almost predictable. Baron Woolf, former Lord Chief Justice, made comments to Lord Blunkett before IPP legislation was enacted that this was a terrible idea. Blunkett claims not to remember the criticism of it, he went ahead and did it anyway. And look what happened. And you know, people have predicted this crisis.

However, one of the biggest problems of prediction is complexity and you can’t just keep people in prison because you think that something might happen in the future.

Faith: Initially an IPP sentence was to be imposed where a life sentence was inappropriate, so where did it go wrong?

Hank: Indefinite detention induces desperation; this is known from psychological research. Induced desperation is a form of psychological torture. There’s plenty of evidence to show that you don’t need more than a couple of weeks having desperation induced in you by this type of prison sentence to suffer mental health consequences. Suicidal ideation, depression, all of these things we hear about over and over again. It’s extraordinary that more people haven’t managed to take their own lives. So, imagine there’s a system which is inducing you to feel suicidal and then to sort of trap you in a suspended animation forever where you can’t kill yourself because they’ve taken away all of the facility for you to do that, but continue to indefinitely detain you. That is like a horror movie. We talk about the “psychological harms” of this, but it is absolutely punishing.

Faith: How has it got to this point where you’ve got so many people dying on a sentence? How has it been allowed?

Hank: It continues for political reasons. These are essentially political prisoners caught in a situation which is way beyond the norm and the political climate is such that it’s very difficult for someone to do something publicly about it. I suspect change may happen quietly in the near future, there will be moves to influence what happens at the parole board hearing, at the prison gate and what happens in various sorts of quiet corners of the system in order to expedite the release of these people while the international community waves its fist at us.

Faith: Bernadette’s story (Episode 6) highlights the ambiguous criteria for prisoners diagnosed with Offender Personality Disorder (OPD) and once on this pathway they are labelled. Why do you think this diagnosis is used against IPP prisoners rather than to help them?

Hank: This is an enormous abuse of power. What’s happened here is a shocking scandal. That’s why a tribunal process might be quite useful because since the invention of the Dangerous and Severe Personality Disorder (DSPD) twenty years ago they were constructing a diagnosis out of thin air for the purposes of managing people in a system, in this case processing them through a criminal justice system. The outcome of that is quite toxic, especially when we know that the incarceration of individuals has severe implications on their behaviour. The National Offender Management Service (NOMS) then implemented the Offender Personality Disorder Pathway (OPD) which might be seen again as a bogus system. It’s invented for management of people who are likely to be disruptive because of the nature of how human beings respond in a prison system.

Research by Robert Sapolsky on neuroendocrinology and research by Daniel Stokols, who is an environmental psychologist, suggests that people in prison systems are very likely to misbehave for many reasons if their circumstances result in a reduction of their agency. If you don’t have a strong identity or a strong sense of purpose, and you are subjected to many of the things that are happening currently in our prison system, you’re very likely to have people starting to suffer mental illness.

Sam: I think most IPP prisoners say I understand my original sentence and the original tariff. It’s what’s happened beyond there I can’t get to grips with and why I’m so distressed by it all. So, I don’t think it’s like shirking responsibility. They do say, okay, fine, I did what I did. Maybe I deserved custodial, but this is beyond what ever should happen to a human being.

Faith: As the OPD Pathway was originally designed for problematic prisoners, do you see any logic in 96% of all IPP’s are given this diagnosis?

Hank: It is cruelty beyond belief. Well, you’re going to be causing trouble if you feel you are being tortured, you’re going to become problematic.

Faith: With Bernadette’s partner, there seems to be little understanding or consideration of how he would struggle when medication for bipolar was withdrawn as a result of a new diagnosis of OPD. Do you see this as a cost-cutting exercise or something else more sinister? Where is the duty of care?

Sam: I think maybe they started with the intentions of cost cutting, this whole sort of merry go round of people being sent to psychiatric hospitals. They thought they could keep it inhouse and that they could label people with personality disorders and keep them inside these NHS units. But then what has happened is that it has become a tool to cage problematic prisoners which people on an IPP sentences will be just because of the nature of what’s happening to them. IPP related distress is not factored in with the OPD pathway, including at parole as we see.

I won’t use the word sinister, but it does feel like it was a way to preventively detain these people. By labelling them as having a personality disorder, or offender personality disorder, which we know is made up.

Faith: The provision of medication or the lack of medication should be a clinical decision and yet it is left to non-clinical staff to determine. Where do you think this failure originates and who is to blame?

Sam: I don’t know the answer to this question. I guess there’s a lot of bureaucracy that comes into this. I think it’s you who said to me that sometimes, prisoners move from prison to prison and their files don’t catch up with them. Then the prison staff don’t even know that they’re supposed to have medication at this time.

Hank: Clinical decisions should be made by doctors. The whole thing with, DSPD and the OPD where clinicians are left out, how can that make sense? Well, one of the reasons is there aren’t enough clinicians working in the system. This prison system creates mental health problems. It’s a double crisis.

Faith: Those in prison should get the same level of health care in prison.

Hank: Well, I have heard some anecdotal stories, some people have said that it’s hard to get mental health support outside prison, they have had better sort of conversations inside prison. It is hit and miss.

Someone who worked in a general hospital told me that the psychology services were downplaying people’s conditions because they knew they couldn’t provide resources to help them. Psychological assessments were being downgraded in the sense that if someone came in and they hadn’t actually tried to commit suicide, but were expressing suicidal thoughts, they were sent home because there was nothing that could be done. That’s extraordinary. That’s just out in the community. And we think the same things happen in prison.

Sam: I really don’t know where to lay the blame on this one. I think in some ways prison governors should have more discretion maybe to help how they deal with their prison.

Faith: In your pursuit of the truth about IPP it appears you have uncovered a further irregularity. In IPP Trapped podcast, Episode 6, Prof Graham Towl, previously Chief Psychologist at Ministry of Justice, says that Dangerous and Severe Personality Disorder (DSPD) was invented not by psychologists but by politicians. This is an astounding revelation.

Sam: The DSPD, a precursor to the IPP, was brought in, in the late nineties. The DSPD and eventually IPP was a way to preventively detain people that they didn’t know what to do with whether that was correct in terms of criminal justice or not.

Faith: Is resentencing the only way to ensure that no one spends the rest of their life in prison despite having not been convicted of an offence of gravity that would warrant life imprisonment or is there some other way?

Hank: The government has re-sentenced people before. Resentencing is the thing that works for justice, but it might be slow, and it may not work well for the emergency that I see. I think this is like a mass casualty situation and it is a crisis with significant humanitarian costs, and it needs to be sorted out quickly. You can’t keep torturing people once you know that that’s what you’re doing. There’s a sort of denial going on amongst the authorities. Re-sentencing is a part of the story, but it might be that there are other things in the nearer term that might be needed to expedite certain people’s recovery. But yes, it’s definitely part of the network of considerations.

Faith: In practical terms how hard is it to change IPP? Must it be legislative change or a judicial change, or a policy and practice change? But in the case of legislation to that end takes time, given the prevalence of self-harm and suicides amongst IPP’s, some don’t have that time.

Sam: I think James Daly MP, often says these people could be in prison 40 years down the line. It sounds incredible, but. Yeah. If nothing is done, it could be 40 years.

Faith: I read that 75% of recalls to prison were IPP’s, yet 73% of these recalls didn’t involve a further offence. Do you think the criteria for recall is too broad?

Hank: Absolutely. This is all about risk aversion. For some reason, IPP’s have been put in this network of problems where risk aversion is of the highest order. Essentially the system assumes that they are the most dangerous people on Earth, and they really aren’t.

The parole board is getting it wrong; the probation service is getting it wrong, the judiciary got it wrong, and the government is getting it wrong. I can’t see any point in the system where they’re getting it right. That’s a frightening thing. We can keep talking about it and we can keep hoping that they will change because the more we talk about it, the less likely they’ll get away with it.

Sam: With recall, there’s the human element of probation officers where they just get things wrong, they are overzealous. One story I heard was someone who had moved address, he’d spoken to his probation officer, and he thought it was approved. A week later, the police collected him from his new address, saying that he breached his license, giving the reason as his change of address. But how did they know the address if the probation officer didn’t tell them? This strange logic that seems to be that the first principle is send them back to prison rather than keeping them in the community and finding the best ways that they can work with them.

Faith: With probation as with prison officers so many have left the profession and you’re left with those with very little experience. You are left with a system run by inexperienced people. So, mistakes will happen.

Hank: Along with the punitive ratchet, the problems in probation are the biggest thing that’s happened in the last 20 years. Everyone’s overloaded. And it’s just a system that’s in crisis again. From the moment you’re arrested for an offence, the police are in crisis, the courts are in crisis, the prisons are in crisis, and the probation service is in crisis. This does not bode well for a quick answer to this. I think this topic should be at the front of the queue for fixing and sorting. The discrimination that someone on an IPP is suffering from where a person who’s committed the same offence, who’s in the same cell or next door who’s getting out after a fixed term, that is discriminatory.

Sam: That’s why they talk about violent offenders when they’re talking about IPP and don’t look at the individual cases. Most cases between 2005 and 2008, were not serious crimes.

Hank: The whole thing is bewildering. I hear myself say “I can’t believe this is happening in our country”, especially a country that used to pride itself on having one of the better criminal justice systems. Other countries model their justice systems on the British system, and it turns out we’ve got the most rotten system around.

Faith: The criminal justice system is in such disarray, isn’t it?

Hank: Despite all the independent monitoring that goes on, it’s very hard to imagine that there’s not a lot more going unreported.

Faith: In your opinion is the current Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice, Rt. Hon Alex Chalk KC MP, going fast enough to resolve IPP in his tenure or will he too run out of road before the next General Election is called and purdah prevents any further progress being made.

Hank: I do think that Alex Chalk is listening and we’re getting messages that he’s thinking about what else to do. Then there’s this interaction with the United Nations. And we also know that there are news stories in the pipeline in the next few weeks. The weight of pressure for change on the system is as strong as it’s ever been. The campaigners who’ve done things have done amazing work. MPs are now better informed than perhaps they have been for some time. It is a window of opportunity. It may be that there’s judicial processes that haven’t been thought of because if the United Nations have stated that this is a particular problem, then perhaps there is a legal route that hasn’t been considered before because the United Nations hadn’t made a statement. But now that they have, now that the light is shining on the topic in a way that it hasn’t for a while, I think perhaps, you know, judicial processes might come to bear that haven’t been used before.

Sam: There is also the Victims and Prisoners bill. I’m not sure what happens if a general election comes along, but I think that’s what Sir Bob Neill is counting on if behind the scenes they’re not able to persuade Alex Chalk about re-sentencing.

Hank: It is a good idea. And there’s another amendment proposing an IPP advocacy role for supporting individuals at the parole board and in other ways. But both of those things are slow in coming into force. If there was legislation, it will still take a year. When you’re talking about a few years for anything to come of that, it isn’t very hopeful, is it? We want things to happen now. I think executive action is more likely to solve the problem in the shorter term. But yeah, I fully support everyone doing everything they can in the legislative process.

Thank you for reading to the end of the interview. The topic has engaged you and, hopefully, informed you. But what now – what will you do with what you now know?

There are several things you can do:

1). Write to your MP

Everyone can write to their MP about what you think about IPP sentencing. If you don’t know who your MP is, you can search via the ‘Find You MP’ via this link [ https://members.parliament.uk/members/commons ]. Simply put in your postcode and the page will give you their name and contact details.

2). Social media

If you use a social media platform you can share your thoughts about the IPP sentence. If you want some ideas, you can share a link to the ‘Trapped’ podcast series, or share a link to this blog interview. Or both.

3). Support a campaigning group

You can find a group which campaigns for change in the IPP sentence. There are several. Why not start with the one called UNGRIPP. Their website is www.ungripp.com They are on Facebook and on X, formerly Twitter.

4). Above all, please don’t do nothing.

Prisons make more problems than they solve

Recently I watched again the movie ‘Erin Brockovich’ about a woman determined to get justice. My brain became filled with questions but instead of going to bed I decided to write and to capture what was in my head.

How many times will I have to read reports from the IMB, from the Inspectorate, from the PPO, all saying the same thing year after year?

How many more times will I have to read about the misery in prisons, the terrible food, the conditions that prisoners live in?

How much longer will I have to read about self-harm, deaths in custody, suicides and not just of prisoners?

How many more campaigns will I read about from organisations trying to better the system, yet very little ever changes?

Are there too many individuals and organisations wrapped up in “Prison works” and patting those on the back who are “heroes” or something. Meanwhile, watching this space carefully, it appears to me that senior members of HMPPS are beginning to jump ship.

Ministers come and ministers go but, looking at reality, I wonder what they are actually doing to bring to an end the misery and violence within our prisons. Yes, I say our prisons because our taxes pays for them. It’s like pouring money into a black hole.

Oh, and what about Rehabilitation?

What about Education?

Yet still we build more warehouses and more warehouses that don’t work, have never worked and I doubt will ever work in the future. And for what reason? Just this week the new Five Wells prison has come under scrutiny, missing the mark in many areas already just a year after it officially opened. Shortages of food, availability of drugs, turnover of staff, all this causing deficiencies reasoned away simply as “…considerable challenges that come with opening a new prison”.

We read about other prisons where those imprisoned for sexual offences have not had the opportunity to address their issues and their crimes are released back into society, homeless. Others who were given an IPP sentence languishing in their cells, not knowing when or if they will even be released. And also those imprisoned under joint enterprise.

We are making more problems, not solving them.

Despite what some people say, In the last 5 years I have visited many prisons. For example, I have delivered training to Custodial Managers and Prison Governors (Wandsworth), twice eaten at a restaurant in a prison (Brixton-Clink), attended an art exhibition in my local prison (Writer in Residence, Warren Hill), observed courses (Chrysalis, Oakwood), celebrated with prisoners on completion of their courses (Stand-Out, Wandsworth) and many more opportunities to talk with Governors. I have seen for myself some of the issues facing staff and prisoners.

Surely there is a better way.

If all we can do is build more prisons.

Prisons boast “we have in-cell technology” as though it’s like something from another planet.

Prisons boast “we have in-cell sanitation” as though it’s a gift when this should be standard.

Almost a year ago a Judge told me that even though they sentence people to custodial sentences, they had never set foot in a prison themselves. I sent a quick message there and then to put them in contact with someone I knew who could help change that.

Prison should be the last resort, and only for those that are a danger to society. Yet, there are people in prison who are there because it is deemed a safe place.

Prisons are not safe, not for prisoners and not for staff. If you don’t believe me then please do some research.

Overworked, underpaid and inexperienced staff working in difficult conditions.

Conditions deteriorate whilst the population increases.

In August 2019, I accepted an invitation from Rory Geoghegan to a speech on ‘Reducing Violent Crime’ hosted by the Centre for Social Justice. Rory gave me a copy of a paper he had co-authored with Ian Acheson called ‘Control, Order, Hope: A manifesto for prison safety and reform’, three things which in my opinion are severely lacking in our prisons. Rory had contacted me the previous September for my view on a key recommendation concerning IMB’s for this paper, as you can imagine I was pleased to read:

“Independent Monitoring Boards (IMBs) have a role to play, to “monitor the day-to-day life in their local prison or removal centre and ensure that proper standards of care and decency are maintained. In the wake of utterly unacceptable conditions across so many of our prisons, there must be questions about how effective IMB’s have been at ensuring standards of safety and decency have been met.”

Recommendation 59: Government to consult on the role and effectiveness of Independent Monitoring Boards (IMBs) to help ensure that they can play their vital role within the wider system of prison governance, early-warning, and accountability.

Source: page 64 and 65 https://www.centreforsocialjustice.org.uk/library/control-order-hope-a-manifesto-for-prison-safety-and-reform

As you can see here, and elsewhere in The Criminal Justice Blog, I have been consistently calling this out for years. The IMB has never been able to ensure anything; if it had then it has completely failed in its remit, as evidenced by the decline in the state of prisons in England and Wales.

Now the prison estate is running out of space, police station cells are on standby, not-so-temporary prison accommodation is being installed as ‘rapid deployment cells’.

Yet still we fill them.

What on earth are we doing?

When will a Secretary of State for Justice make a stand, be decisive and finally bring some control, order and hope into our prisons?

~

The watering down of prison scrutiny bodies

I want to concentrate on two scrutiny bodies: His Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons (HMIP) and the Independent Monitoring Boards (IMB).

It appears that both have changed their remit to compensate for the ineffectiveness of their scrutiny. Are they trying to improve something, or are they trying to hide something?

Does the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) want these bodies to obfuscate the facts of the state of prisons? The dilution of scrutiny results in degradation of conditions for your loved ones in prison, staff and inmates alike, both in the same boat.

His Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons (HMIP)

Website https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons/

HMIP inspections have routinely issued recommendations to prisons where failure in certain areas needed to be addressed and in cases where it is possible for issues to be rectified or improved. Applying the healthy prison test, prisons are rated on the outcomes for the four categories below:

- Safety

- Care

- Purposeful activity

- Resettlement

Since 2017, if the state of a prison is of particular concern an Urgent Notification (UN) has been issued. This gives the Secretary of State 28 calendar days to publicly respond to the Urgent Notification and to the concerns raised in it. There have been twelve Urgent Notifications issued so far, and the details from the latest urgent notification for HMYOI Cookham Wood, for example, is uncomfortable reading:

“Complete breakdown of behaviour management”

“Solitary confinement of children had become normalised”

“The leadership team lacked cohesion and had failed to drive up standards”

“Evidence of the acceptance of low standards was widespread”

“Education, skills and work provision had declined and was inadequate in all areas”

“450 staff were currently employed at Cookham Wood. The fact that such rich resources were delivering this unacceptable service for 77 children indicated that much of it was currently wasted, underused or in need of reorganisation to improve outcomes at the site.”

Source: https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2023/04/HMYOI-Cookham-Wood-Urgent-Notification-1.pdf

However, the Inspectorate now have a new system where recommendations have been replaced by 15 key concerns, of these 15, there will be a maximum of 6 priorities. On their website it states:

“We are advised that “change aims to encourage leaders to act on inspection reports in a way which generates real improvements in outcomes for those detained…”

Source: https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons/about-our-inspections/reporting-inspection-findings/

One of my concerns is whether this change will act as a pretext to unresolved issues being formally swept under the carpet. A further concern is what was seen as a problem previously will now be accepted as the norm. As a consequence how will the public be able to get a true and full picture of the state of the prisons?

Will there be a reduction in Urgent Notifications?

I think not.

Or will the issuing of urgent notifications be the only way to get the Secretary of State for Justice to listen and act? In my view, issues that would previously have been flagged up during an inspection are more likely to disappear into the abyss along with all past recommendations which have been left and ignored.

Could it be said that this change of reporting is a watering down of inspection scrutiny that you expect of the Inspectorate?

Before you answer that, let’s look at the IMB.

Independent Monitoring Board (IMB)

Website: https://imb.org.uk/

Until very recently, the Independent Monitoring Board (IMB) website stated that for members: “Their role is to monitor the day-to-day life in their local prison or removal centre and ensure that proper standards of care and decency are maintained.”

But looking at the IMB website today I have noticed that they have changed their role. Instead, it now states that members: “They report on whether the individuals held there are being treated fairly and humanely and whether prisoners are being given the support they need to turn their lives around.”

Contrast that with what the Government website http://www.gov.uk displays, where you will find two more alternatives to what the IMB do:

- 1st. “Independent Monitoring Boards (IMBs) monitor the treatment received by those detained in custody to confirm it is fair, just and humane, by observing the compliance with relevant rules and standards of decency.”

Source: https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/independent-monitoring-boards-of-prisons-immigration-removal-centres-and-short-term-holding-rooms

The first is a large remit for volunteers as there are rather a lot of rules to be aware of. I’m sure the IMB training is unable to cover them all, so how can members be required to know if the prison is compliant or not.

- 2nd. “Independent Monitoring Boards check the day-to-day standards of prisons – each prison has one associated with it. You don’t need specific qualifications and you get trained.”

Source: https://www.gov.uk/volunteer-to-check-standards-in-prison

This checking comes across as a mere tick box exercise, which it certainly should not be. Again, I question whether IMB members training is sufficient. What they say and what actually happens is another example of the absence of ‘joined-up’ government.

In point of fact, the IMB has never been able to ensure anything; if it had then they have completely failed in their remit, as evidenced by the decline in the state of prisons in England and Wales. Clarifying their role is an important change, and one I have been calling out the IMB on for years.

Could it be said that this change of wording is a watering down of monitoring scrutiny you can expect of IMB members?

To help you answer that, you may also need to consider the following:

Although the IMB has become a little more visible, I still have to question their sincerity whether they are the eyes and ears in the prisons of society, of the Justice Secretary, or of anyone else?

The new strapline adopted by IMB says: “Our eyes on the inside, a voice on the outside.” Admirable ambition, and yet compare that with the lived reality, for example, of my being the eyes on the inside and a voice on the outside, which was exactly the reason why, in 2016, I was targeted in a revolt by the IMB I chaired, suspended by the then Prisons Minister Andrew Selous MP. For being the eyes on the inside and a voice on the outside I was subjected to two investigations by Ministry of Justice civil servants (at the taxpayer’s expense), called to a disciplinary hearing at MoJ headquarters 102 Petty France, then dismissed and banned from the IMB for five years from January 2017 by the then Prisons Minister, Sam Gyimah MP.

If the prisons inspectorate have one sure-fire way of attracting the attention of the Secretary of State for Justice in the form of an Urgent Notification, then why doesn’t the IMB have one too? Surely the IMB ought to be more aware of issues whilst monitoring as they are present each month, and in some cases each week, in prisons. Their board members work on a rota basis. Or should at least.

And then of course there is still the persistent conundrum that these two scrutiny bodies are operationally and functionally dependent on – not independent of – the Ministry of Justice, which makes me question how they comply with this country’s obligation to United Nations, to the UK National Preventative Mechanism (NPM) and Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and other Cruel Inhuman of Degrading Treatment or Punishment (OPCAT), which require members to be operationally and functionally independent.

In 2020, I wrote: “When you look long enough at failure rate of recommendations, you realise that the consequences of inaction have been dire. And will continue to worsen whilst we have nothing more compelling at our disposal than writing recommendations or making recommendations.”

and: “Recommendations have their place but there needs to be something else, something with teeth, something with gravitas way beyond a mere recommendation.”

As a prisons commentator I will watch and wait to see if the apparent watering down of both of these organisations will have a positive or detrimental effect on those who work in our prison environments and on those who are incarcerated by the prison system.

As Elisabeth Davies, the new National Chair of the Independent Monitoring Boards, takes up her role from 1st July 2023 for an initial term of three years, I hope that the IMB will find ways to no longer be described as “the old folk that are part of the MoJ” and stand up to fulfil the claim made in their new strapline: “Our eyes on the inside, a voice on the outside”.

And drop the misleading title “Independent.”

~

Photo: Pexels / Jill Burrow. Creative Commons

~

A Conversation With: Simon Israel: Giving People A Voice.

A couple of months ago, I travelled to Edinburgh to interview Simon Israel, Former Senior Home Affairs Correspondent at Channel 4 News.

I braced myself for the weather and arrived by train in a storm where an umbrella proved completely useless. Yet within half an hour a rainbow welcomed me to my stay at The Royal Scots Club. I invited Simon to join me there and what a wonderful opportunity we had to talk and have lunch together.

FS: How did it all start?

SI: I studied maths and logic at Aberdeen University. I hated it, but I did it. Whilst there I got involved in the student newspaper and I thought it was wonderful. No rules.

I came out of university and thought I’m going to be a broadcast journalist in radio. Commercial radio was booming, so there were loads of jobs out there. I did 3 months at the National Broadcasting School, Soho then started off in local radio. I then arrived in London LBC IRN and was there for an awful long time, maybe too long, probably. Working in local radio I really had a brilliant time. I went all over; India, South Africa, Bosnia during the war, Kenya, and various places in Europe. I did lots of things.

Then ended up at ITN – pissed off the editor in radio who suggested I might want to go to another department.

I went to Channel 4 and said, “I know nothing about TV.”

“Ok, we will take you,” they said.

I knew a lot about journalism and stayed at Channel 4 for more than 25 years. I loved the ethos of Channel 4 News, that is where I think I fitted better than anywhere else.

FS: When I have listened to your reporting, there are very few what I call Happy Stories.

SI: No, I don’t do happy stories, well, I’ve done one or two but not very many. I drifted into the area of Criminal Justice and Policing, and it is not a world of happy stories; it never is really.

FS: So, you have focused on injustice.

SI: I think that was a very key theme, it manifested itself in various ways.

I came back to this idea that of giving people a voice that would struggle to get one.

I dabbled in politics, but nothing in politics is secure for very long. Everything is a moveable feast in politics, and I found that difficult as I needed a set of actions that I can build on. That’s a fact, that’s a fact, that’s a fact. I cannot build on X has got an opinion, or X tells me this is what is going on.

FS: Does that prevent people accusing you of bias?

SI: They can accuse me of bias – I can only be biased if I skew things so much that I’ve distorted the story. I try very hard not to.

This is the world of entertainment – radio-television, so it is not the same as newspapers as its dependent on pictures. In radio I felt much more secure because you could tell things straight.

My idea was if the person stopped watching or listening within the first 5 or 10 seconds, however long the rest of the piece was, I would have lost the whole point of why I was doing it. So, I was conscious all of the time however long or short the report was, I had to keep their attention.

FS: I suppose it is like that with writing a book you have got to keep people’s attention.

SI: You have to keep them going to the end, they have got to be interested, outraged, sad or anything that can sustain their attention throughout the whole thing. It’s not about whether you liked it or not, might agree or disagree with it. I think you get to the end to allow a justifiable thought about whatever it was that I was reporting on.

Someone would say “I watched you, but I got distracted after a few minutes, then I failed didn’t I.

FS: Do you go back and listen?

SI: I could have gone back in post-mortem style.

Most of the stuff I do people were interested in, they are interested in grim stuff. I’ve been told by an editor:

“Make them cry in front of the camera.”

I said, “Excuse me.”

I can see where the editor is coming from, and you can learn to some extent. There is an element of manipulation sometimes because you know what sort of questions might produce, for example a tear. I know that sounds weak, you do try and avoid as there’s a tendency to say I am here because I am praying on your emotions, I’m not here to give you a voice or find out a different view to what’s happened.

So to that classic question “How do you feel?” How would I feel being asked the same question?

I interviewed Mina Smallman in her house. I broke the story along with Vikram Dodd, we both had different sources.

I had sat on the story for 2 or 3 days, because I couldn’t get a second source. There was a risk other people knew what I knew. I always have to have 2 sources; they might not necessarily know the same things, but they have to share the knowledge (some agreement in what they know) that something happened.

In the process, the Met Police behaved appallingly, they wouldn’t confirm or deny anything. They wouldn’t give us a statement until we said we are running this tonight and the Guardian are running it too. We will just say you refused to comment.

We turned up at her doorstep to deliver a letter saying what we knew and the person at the door said Martin Bashir was there with a camera and she is not talking at the moment. Mina Smallman knew Martin Bashir (Religious Correspondent editor) as she was in the clergy at Chelmsford Diocese.

It took me many months to persuade her to talk to me, partly because of what she was going through, losing her daughters, the way the Met Police had treated her and the trial etc. at that time the investigation was still live. God knows what was going through her mind.

FS: When you have to cover stories such as that, where does your strength come from, family, colleagues?

SI: No, no. I don’t know. It comes from 30 years of experience. I don’t know, I’ve never been asked that before. You just do it.

I like to think I am very sensitive to other people’s emotions. I realise that many of these interviews are not easy for them. Easy for me; I just ask the questions, pack up and leave. If they have agreed to do one then somehow, they manage to find the strength from somewhere.

FS: So, you give people a platform to be able to speak?

SI: Yes, I’ve watched interviews where some get others to speak in quick 20 second terms. But to engineer answers out of people to me is wrong. It’s not my job to tell people how to answer the questions. I’ve watched interviews where they have asked the interviewee to leave off bits.

I can’t do that.

I’m not here to try and engineer people into saying things that are convenient to me.

FS: When you interviewed me in 2017 that never came across. You asked the questions fairly sensitively, managed to get the main points over and it fitted with the story.

SI: You gave a very good interview, I didn’t tell you how to do it, I didn’t tell you how to answer the questions.

I did a story over a period of time on student suicides, that was really difficult as I have attended enough inquests to understand the utter vacuum created by someone who has killed themselves. The family find it nigh on impossible to come to grips with something like that.

When someone has been killed by another, there is a focus on the other person, trial – justice – truth. But in suicide it’s a completely different world and the self-blame and anguish constantly thinking “I should have done something”.

Families tend to throw themselves into campaigns, a way of managing their own conscience, I think.

FS: To try and raise the issue so that others can be prevented from going through the same?

SI: Yes, there are limited positive ways of moving on.

When you interview you can’t ask “how much do you blame yourselves for…” and even if you got an answer would it be a fair answer anyway?

Unless someone has left a note or have explained in detail why they got to the point they have, it doesn’t stop people thinking.

If I had known…

I would have made sure…

I would have done this…

Their own memory can become distorted because they did all those things anyway.

In reporting on efforts to get justice, you have to be minded that people see justice and tragedy in different ways, so they need to be handled in different ways.

You sub-consciously learn if I am really honest the ways to try and allow people to have the freedom to say what they want to say, yet make sure you are still independent. To be fair to a story is trying to figure out where in a vague sense the truth is – that sounds a bit worthy. You go for what you think or may come closest to the truth. That’s part of your role as a journalist. You may not find the truth; you would be naïve to think if you did. It you get closer to it, that’s as good as you can do really.

I have covered a lot of prison deaths where I found things utterly appalling and wandered off thinking “why can’t I get the public to care more about this than they do”. Gaining public sympathy is a real uphill struggle even when I have seen things that are so outrageous and I’m going, “why aren’t they the responsible all banged up?”

FS: Where’s the accountability?

SI: That’s my argument, it effects the system so much that they are so used to being too avoiding that the politician is the same “I’ll get no votes…”. Most of these people in prison will come out and end up being someone’s neighbour at some point… SO GET THEM READY.

I appreciate prisons have been in crisis for years, this isn’t new today. But we’ve done that classic thing where we park that world in a layby and just shrugged our shoulders.

FS: Do you believe we live in a punitive society?

SI: We live in a society full of cowards, utter cowards, can’t stand up and say “do you know what, this can’t happen anymore”

When you look at the Children’s Commissioner stand up because they know they will get an audience and so people will listen when they shout. But once someone is 18 and someone stands up and says exactly the same thing, people will stop listening and that’s ridiculous. It’s not rational really, it’s absolutely ridiculous.

FS: You are working with Frances Crook at the moment – a commission – what is this and what is its aim?

SI: Her background is essentially a Labour one. Frances took me to lunch and asked if I would like to be on this panel looking at the relationship between the Executive and the voter. Essentially the shape of democracy, but it was also designed to fit in with the end of the reign of Queen Elizabeth II, the start of a new monarch and the idea that, somehow or other, there had to be a better way of holding the Executive to account following the recriminations over Boris Johnson and his government, basically. So, because Britain doesn’t have a constitution in reality, it was designed to look at what a better system could have for holding the executive to account.

But how do you hold the executive to account when they go off piste and create all those walls you have to climb and moats you have to cross where you go “Drawbridge is up, you cannot come in”?

I get the point.

You come back to the journalism; the unelected part of the journalism is not really just to call people to account but to change things.

I was always trying to do stories to be a factor in trying to change the thing that wasn’t right. I have done that once or twice; I know I have. It’s not that I have moved mountains, but I’ve improved the lives of people of individuals, so that makes it worthwhile to me.

An example was the Cherry Groce case. I have to say legally, was accidently shot by a police officer in a raid on her home looking for one of her sons, who wasn’t there, this sparked the 1985 Brixton riots. She was paralyzed and ended up in a wheelchair for the rest of her life. In that room where she was shot was her son Lee aged 11 years.

A police officer was put on trial and was acquitted. After Cherry’s death, in 2011, the pathology report linked the shooting and the kidney failure that led to her death. This in turn triggered an inquest. Cherry had lived longer than what was expected, and the trial had never addressed the circumstances on how his mother came to die.

I was at Channel 4 at the time and received a tip off about the pending inquest. I contacted Lee to ask if he would be willing to talk. He said, “I’ll get back to you”. He never did, and I never saw any write up of this inquest.

About a year later he called me, “I think I need your help.”

“The police have a secret report which they won’t let me see, damming of the Met and I can’t get legal aid for the inquest, which has been delayed. All the other parties have QC’s, and they won’t give me legal aid.”

I said we are going to do a story, I did a piece which was well received. To force things to happen a petition was put up on change.org and once the story was out the signatures increased to 120,000. We had started the motion and the Lewisham MP got involved by banging on the door of the legal aid agency and managed to get Lee legal aid.

Lee got his unlawful killing verdict, the Met had to release the report and the man that shot Cherry came to give evidence.

Lee walked away saying “That was for my mum, I got it”.

The head of the Met apologised face to face and the family were paid compensation as the original money paid out was to cover only up to 10 years as that was the estimate of how long Cherry would live after being shot. She lived 16 more years with the financial burden on the family.

In 2020, Lee Lawrence won the Costa Biography Award for his book “The Louder I Will Sing: A story of racism, riots and redemption”.

In Brixton Square there is a huge structure put up by the Met Police to honour the life of Cherry Groce.

So I made a difference.

FS: What makes you laugh?

SI: Children make me laugh, I love children, their humour is instantaneous.

FS: What makes you cry?

SI: I’m not sure loss does, I lost my dad, but didn’t cry, quite a long time ago. Will I cry if my Mum died? Not so sure, not because I don’t love them or care about them.

I sometimes cry out of frustration and sometimes out of appreciating someone’s hurt. The sheer inhumanity of it all. I cried in Rwanda when we picked up a desperately injured child and took them to hospital. I think I cried out of the sheer chaos of everything, and this manifested itself on this poor child who had no control over anything. I had met them for half an hour max.

I manifest my emotions that are linked to other people’s emotions I think, whoever that might be rather than my own.

I’ve led a fairly happy life; I haven’t suffered really in any shape or form that I can say is relevant to anything.

I had a great childhood.

I had a great education.

I had a relatively great career, maybe I didn’t get all the way to the top, but that didn’t matter. I got to do what I wanted to do and still do.

You look back and say, “I can’t really grumble.”

~

Photographs used by kind permission of Simon Israel.

~

Penitence versus Redemption in the Criminal Justice System: Unedited

I once entered a cell of a high-profile prisoner; his crime had been blazoned on every national newspaper and was serving the last few months of his sentence as an education orderly. He sat on his raised bed, his legs dangling over the menial storage where he had meticulously and precisely arranged his pairs of trainers and invited me to sit on the only chair in the cell. During our 20-minute conversation, he was pensive and reflective, looking down all the while, except for when he raised his head, adjusted his glasses, then looked me straight in the eye.

“Don’t count the days, but make every day count,” he said, his voice monotone and hushed. Yet behind him, I noticed a calendar marked with neatly drawn crosses. He was clearly counting down his days, paying his penitence until his eventual release from prison.

As an independent criminologist, I have met many who feel a deep-seated obligation to “pay back” continuously in some way to society or a higher power. Those who are caught and convicted for committing a crime experience punishment in some form or other, but when should that punishment end? Is it once a sentence has been served or longer?

Over the last 12 years, I have visited every category of prison in England and Wales and monitored a Category D prison for four years. In all that time, I have encountered hundreds of inmates, many struggling with the punishment, not only that of the sentence given by the courts, but the continual punishment they experience as they serve it, as well as after release and beyond.

The Ministry of Justice proudly states on their website that their responsibility is to ensure that sentences are served, and offenders are encouraged to turn their lives around and become law-abiding citizens. Apparently, the Ministry has a vision of delivering a world-class justice system that works for everyone in society, and one of four of their strategic priorities is having a prison and probation service that reforms offenders.

But I am not at all convinced by this hyperbole. In my opinion, we must stop the madness of believing that we can change people and their behaviour by banging them up in warehouse conditions with little to do, not enough to eat, and sanitation from a previous century.

Penitence

If true reform is supposed to be achieved through time served, then a former inmate emerging from prison with a clean slate would be ready to contribute fully to society. Yet beyond prison gates people who have served their time all too often live under a cloud of penitence, suppressing a sense of guilt for their deeds.

Many of the formerly incarcerated insist on a daily act of penitence, a good deed, even raising money for a worthy cause. For onlookers, such acts carry an air of respectability, but it is important to understand what is really happening on the inside because some of those who engage in them do so as a form of self-punishment. The punishing of self both physically and mentally.

They sense they must compensate.

Their account never fully paid.

Lifelong indebtedness.

And of course there are those who appear to genuflect to the Ministry of Justice and the Criminal Justice System; a sign of respect or an act of worship to those always in a superior position.

On the balance of probabilities, it is more likely than not that some penal reform organisations and some individuals with lived experience approach the Ministry of Justice with such reverence showing their cursory act of respect.

The same act of penitence or faux reverence ingrained into them whilst they served their custodial sentence.

For others penitence is an act devoid of meaning or performed without knowledge.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the definition of penitence is “the action of feeling or showing sorrow and regret for having done wrong, repentance, a public display of penitence.” In addition to the formal punishment they endure, many prisoners engage in penitence both physically and mentally during and after serving their time, which keeps them from moving forward with their lives and is damaging to their sanity.

According to a 2021 report by the Centre for Mental Health, (page 24) “former prisoners…had significantly greater current mental health problems across the full spectrum of mental health diagnosis than the general public, alongside greater suicide risk, typically multiple mental health problems including dual diagnosis, and also lower verbal IQ…and greater current social problems.”

In my work, I have found that some people who have broken the law want others to know that they are sorry, whilst at the same time feel the pressure to prove this to themselves. In such cases, their penitence becomes a public display for families, caseworkers, and those in authority.

Witnesses to this display of penitence often think these people are a good example of someone who has turned their life around, but often, these former prisoners find themselves stuck in the act of penitence. Rather than turning their lives around, they are trapped forever in their guilt. In these cases, the act of atoning becomes all-consuming, an insatiable appetite to heed the voices in their soul that tell them, “you must do more and more, it’s not enough, I’m hungry.”

Redemption

When I speak to those who are serving a whole-life tariff, I know that their debt to society can never be repaid: they are resigned to a lifelong burden of irredeemable indebtedness. But many of those who are released from prison remain incarcerated by their own guilt, feeling as if they must hide any hint of happiness they may find in life after prison so as not to be judged.

For example, in 2019, I interviewed Erwin James, author, Guardian columnist and convicted murderer, who had just come out with his third book, Redeemable: a Memoir of Darkness and Hope. When I asked him, “What makes you happy?” he replied: “In the public, if I am laughing, I feel awful because there are people grieving because of me. Even in jail, I was scared to laugh sometimes because it looked like I didn’t care about anything.”

Just like I saw with the prisoner sat on his bed, I have witnessed a cloud hanging over many, especially when redemption, or the act of repaying the value of something lost, relates to acceptance and society’s opinion of you.

There are of course prisoners who have the intellectual capacity to learn from their mistakes, have the emotional capacity to adapt to their situations and – not forgetting – the spiritual capacity, a dimension that can lead to a voyage of self-discovery. But by no means all.

Unfortunately, in the UK, paying back to society can either be the light at the end of the tunnel, or a tunnel with no light.

I believe we live in a punitive society in which the continual punishment of those who have offended is tacitly endorsed. In so doing, society inadvertently encourages the penitentiaries of this world to hold offenders in an ever-tightening grip.

Even a sentence served in the community—a sentencing option all too often shunned by magistrates—can carry an arduous stigma. In a public show of humiliation, the words “Community Payback” are garishly emblasoned on the offenders’ brightly-coloured outerwear, announcing their status as a wrongdoer to all who see them. Basically, this is society’s way of saying, “we want you to be sorry, we want you to show you are sorry and we will not let you forget it.”

Statements such as “the loss of liberty is the punishment” become fictitious, enabling punishment in its various form to continue throughout the sentence served and even after release.

Let us no longer have this traditional stance, rather should we try to embolden others to move on from their actions?

And can groundless nimbyism be finally assigned to history?

I am mindful that pain and grief still abounds, that some crimes will not be erased from our minds, and that crimes will stubbornly continue. But surely, the answer cannot be to condemn those who have done wrong to a lifetime without forgiveness.

To move forward as a society, we need to discourage the continual need to offer an apology, and instead accept when former prisoners have paid their dues and served their sentences. Only then will we move from a vicious cycle of unending penitence to a world in which reform and redemption is truly possible.

~

An edited version of this article was first published on 28 February 2022 by New Thinking.

~

IMB Soap Opera

Is the IMB like liquid soap?

Not the wonderful clear stuff which has a beautiful fragrance and an antibacterial effect on everything it touches.

No, not that.